The art of violence

by Mika Provata-Carlone

“Brilliant, terrifying and compelling.” Observer

What an artist perishes in me, lamented Nero as he prepared to end his life before the rebelling senators had time to dispatch him. “He had indeed been an artist – he and his predecessors too” writes Tom Holland in the concluding pages of his sweeping survey of the Julio-Claudians, which delineates the rule of Augustus, Tiberius, Caligula, Claudius and Nero as titanic exercises in the art of immortality – an art which invariably involved a pragmatic understanding of absolute authority and government, and a ruthless, insouciant espousing of vice and violence.

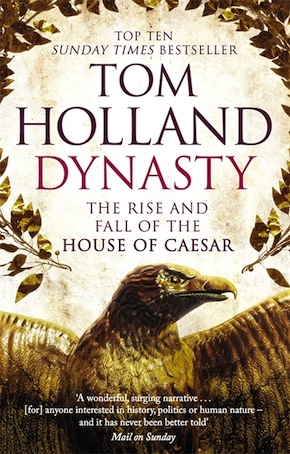

Holland is a meticulous and masterful historian – and a particularly alert and captivating storyteller. Dynasty: The Rise and Fall of the House of Caesar is a fiery, racy, unflinching chronicle of what was perhaps the most vicious, glorious and flamboyant century in Roman history. There is something of the ancient historiographer about Holland. He shares Herodotus’ fascination with local lore, for all that is exotic and unknowable, the minutiae of geography, ethnology, mythology, foundation stories and scandalous origins – above all, for thrilling tales of power beyond human limits or the wildest imagination.

Also like Herodotus, Holland is scrupulous about poring over and synthesising sources, giving us in Dynasty a riveting anthology of tales and anecdotes of the times, as they were told and as they happened, with all their flaws, contradictions, intriguing revelations, omissions or distortions. He seems, too, to share passionately the relish for human psychology, pathology and socio-dynamics of Tacitus, Suetonius, Livy or Pliny, as well as the conviction that shrewd analysis and ineffable complicity can be startling companions, per Cicero and Seneca. Rather than tiptoeing around the stark, harsh, harrowing realpolitik and social mores of the first century AD, Holland determinedly points out the nature and causes of most things Roman: “a pitch of violence more bestial than human” that lay at the core of the myth and wonder that was Rome. Drawing on Rome’s foundation myth of Romulus and Remus, Holland follows the trail of enchantment and brutality that ensued. The Romans, unlike the pedantic, predictable and by now past-their-expiry-date Greeks, were a race possessing the “chilling quality of creatures bred of myth” – and especially the invaluable, omnipotent art of imperial spin.

At the beginning, there was Augustus, “the one-time terrorist promot[ing] himself as a dutiful public servant.” With cutting clarity and a good dose of irony and wit, Holland unravels the first emperor’s carefully woven humble garments to expose the systematic layout of a new global order: an era where recollection of fact was swiftly and resolutely replaced by revised blurred memories and new beginnings, where recovered or reinvented tradition and ambition intertwined and converged in the mind and power of a single man, Augustus himself. Holland pieces together processes and intentions, acts and motives, and convincingly argues that Octavian conveniently “invented… venerable customs” in order to achieve his greatest claim, the Res Publica Restituta – the restoration of the republic. He lifts veil after veil of illusion, demystifies claims and visions of peace and grandeur, of the reality of power and stability, unmasking aims and means without condemning outright: the times were dire, the minds and hearts of the citizens of Rome were worn beyond endurance and despair.

Dynasty captures the imagination as much as it satisfies the mind with its richness, depth, rigour and scope, the clear articulation of angles and positions, Holland’s thrilling, twinkling eye for philological detail.”

Throughout, Holland steps back to let others speak for him: poets, historians, philosophers, anonymous writers of inscriptions are urged to tell their story, and these disparate, fragmented or long-muted voices now spring to life in Holland’s hands, as though released from long captivity. They seamlessly thread their way through Holland’s tale of blood, vice and gore, underscoring tales with facts and scholarship of the most vivid hues. In the process, a certain distinctiveness of timbre and the potential for further analysis is sometimes lost. Whereas we have an intriguing cameo of Horace or Ovid, or later of Seneca, we have little or next to nothing on Cicero and Octavian’s pledge of human sacrifice that sealed the triumvirate. Especially and crucially, we have quotes but no living presence or personal mention of Virgil, an exclusion that leaves a reverberating vacuum in Holland’s yarn. Such discernment or economy in selection comes at a price: we are deprived of the sense of a more immediate past than Romulus and Remus, a past that contained causes, curses and significant paradigms. Sulla’s proscription lists came before those of the Triumvirs, and Caesar’s decision not to endorse that particular practice may be said to constitute a contrasting alternative of what might have been. As for Cicero, his role during the time between Caesar’s assassination and Philippi would have added critically to the multiple perspectives, adding vital layers of interpretation as well as eliminating shades of ambiguity. The same sense of more would have been more applies to Seneca as well.

That said, Dynasty captures the imagination as much as it satisfies the mind with its richness, depth, rigour and scope, the clear articulation of angles and positions, Holland’s thrilling, twinkling eye for philological detail. Not solely an academic account, nor merely a fast-paced novelised history for a rainy day, this is a serious, fascinating, viscerally gripping book that must be read alongside not Robert Graves’ I, Claudius, but rather Constantine Cavafy’s poems of Barbarians and Alexandrine Kings. It is a brilliant, riveting tale of a masterful polyphony of echoes – an echo itself of the many voices, contradictions, momentous events and tragically lost accounts that make up Roman history.

Holland gives us a warts-and-all portrait of Augustus, an intriguing, more complex profile of Tiberius than we usually come across. We hear of Claudius fighting off a stranded whale at his newly refurbished harbour at Ostia, of his fascination with natural history and hydraulics, his genuine concern for the welfare of the people of Rome (though not necessarily for that of his subjects in far-away provinces), of his scholar’s dogged persistence to add three new letters to the Latin alphabet – which were duly abandoned to oblivion after his death. We learn that Orestes, pursued by the Furies after the murder of Clytemnestra, fled westwards carrying a statue of Artemis, eventually building a sanctuary in her honour at the lake of Nemi, a favourite pleasure spot of Caligula. There the priest would always be a fugitive, a slave or exile, who would accede to the role by killing his predecessor, only to be killed himself by his successor, in an endless cycle of murder after murder. The vengeful Erinyes never transformed into kindly Eumenides in Rome. With each incremental act of individual misuse of power, with each dynastic gesture, the inevitable, terrifying ramification is the sense of a global normalisation of extreme cruelty and violence, or if not normalisation, then an even more harrowing sense of desensitisation, numbing, anaesthesia.

This is a fine blend of the myth, fiction and hard fact, rumour and reality, glory and gore, sharp wisdom and blinding vanity that made Rome all that it was, and provided the framework for what emerges in Holland’s train of thought and argument as a terror of legality that confirmed for itself historical immortality and even legitimacy. Dynasty is an astute, animated and vivid account of the spirit of the era, across the dynastic successors, rich in detail, engrossing in scholarship, inspired in style and with a rare flair for storytelling and for historical analysis on a large scale. Lucid historical analysis and eager observation of individual and group psychology, of human customs and mores, make this a book one wants to savour at length and seriously, even if one would have wished for some additional threads to much of the story, and for a certain occasional close focus – if this is what Rome was like from the inside, how was it perceived by the rest of its contemporaries? What were the parallel or alternative accounts? Or was Rome so absolute that no other perspective existed, even in an embryonic state, anywhere at all? Had the spectacle of the Empire effaced all other visions?

We are still slaves, perhaps now more than ever, of very similar spectacles: the more dazzling, blinding, harrowing, the better we seem to indulge in them, believe them, crave them. Spectacles in politics, society, art, private and public existence have come to replace vision and insight, reflection and true image. At their most savage or in the very midst of the fear and trembling they caused themselves and others, some Romans were also trying to understand the roots and nature of all their darkness and violence, as does Holland in Dynasty. His study of Rome’s most famous, pivotal, transgressive and radical ruling family, the Julio-Claudians, is as much about Rome as it is about us and our own time. The more Rome conquers gloriously and gorily, the more it needs to recalibrate its sense of self, its sense of identity, polymorphy, multi-ethnicity. The balance between cultural distinctiveness and national integration was as hard, as vital, as thorny and controversial, and potentially destructive as it is now. Holland’s great gift is to present us with the ineluctable linearity of actions and of inaction, to force us to sit and stare, stripping away the familiar gloss without leaving us reeling for lack of support. Much of the story requires strong nerves and even stronger stomachs, but above all it pleads for understanding – of the past for the sake of a present and a future.

Tom Holland is the author of Rubicon, which was shortlisted for the Samuel Johnson Prize and won the Hessell-Tiltman Prize for History 2004; Persian Fire, which won the Anglo-Hellenic League’s Runciman Award 2006; Millennium and In the Shadow of the Sword. He is the presenter of BBC Radio 4’s Making History and has adapted Homer, Herodotus, Thucydides and Virgil for radio, and written and presented TV documentaries on subjects ranging from religion to dinosaurs. Dynasty is out now in paperback from Abacus. Read more.

Tom Holland is the author of Rubicon, which was shortlisted for the Samuel Johnson Prize and won the Hessell-Tiltman Prize for History 2004; Persian Fire, which won the Anglo-Hellenic League’s Runciman Award 2006; Millennium and In the Shadow of the Sword. He is the presenter of BBC Radio 4’s Making History and has adapted Homer, Herodotus, Thucydides and Virgil for radio, and written and presented TV documentaries on subjects ranging from religion to dinosaurs. Dynasty is out now in paperback from Abacus. Read more.

tom-holland.org

@holland_tom

Mika Provata-Carlone is an independent scholar, translator, editor and illustrator, and a contributing editor to Bookanista. She has a doctorate from Princeton University and lives and works in London.