Violence without motive: the caged ferocity of adolescence

by Giulia Caminito

ONCE I BECAME AN ADULT, I looked back and saw the teenager I had been: studious, insecure, wary of role models, unable to blend in. That young girl – with vain, golden ballet shoes on her feet – couldn’t understand her peers, and at every moment expected a sudden slap, a pocketknife pulled out, a scream in the middle of the street.

I grew up in the rich and poor suburbs of Rome, where the bourgeoisie – not well educated, but ready to shell out for shoes from established designers and trips to Ibiza – and numerous families of caregivers, domestic helpers and foreigners always coexisted. All through the neighbourhood, one could see both dilapidated hospitals with cracked walls and the gigantic mansions of soccer players and TV actors. In my school, many of the boys dressed up in Ralph Lauren shirts and expensive sneakers, and yet it was often terribly cold in the classrooms, the walls so thin that lecturing and learning was impossible.

Was it these sharp contrasts that sparked sudden flare-ups of aggression? Was it the tense juxtaposition of luxury and misery? For years I didn’t understand it, I didn’t think politically about the urban space I inhabited, I wasn’t aware of what surrounded me.

In fact, when I was in high school, it seemed normal that outside the school, there was always someone waiting to beat up one of my classmates. The gang leader would wait for my classmate to come out of the gate, and the boy and his friends would punch and belt him. I would watch this happen, or change my route, go through the back of the building and hurry away. Once a friend of mine was beaten across the back with a steel chain from a scooter. The reasons were illogical, very stupid: he had glared at someone at a party, he had been rude at recess, he had smiled at an engaged girl.

I remember my friends with swollen eyes or stitches across their foreheads. I remember their older brothers coming to escort them home safely, only for it to start all over again the next day. The violence was sticky and stubborn, like a grease stain on a new jacket.

Across all these senseless attacks, there was a total absence of motive: the violence was an end in itself. It only served to reaffirm the capacity for attack, the ability to dominate and instil fear. The boys in my neighbourhood walked with their chests out and legs apart, insulted each other in dialect. The more broad-shouldered friends you had, the more protected you were, because you could always call them to your aid. I witnessed countless rallying calls for punishment: to go and beat up one guy or another, to flush him out of the car where he had taken refuge, to set fire to his scooter.

The memory of this violence had been buzzing around my head for years, and I felt the need to write about it because I wanted to investigate it, get closer, understand it better.”

It was normal for even friends to hit each other, especially after bingeing on cocaine or beer. I saw them, midway through a debaucherous afternoon at the lake, argue over some nonsense and hit each other so violently that they passed out covered in blood. Close friends who had known each other since kindergarten, people who went out together every day and yet still vented their frustration at each other in the ugliest of ways.

This is what we were taught as teenagers: to suffer this violence, to see it happen and to say nothing, especially as young females.

The memory of this violence had been buzzing around my head for years, and I felt the need to write about it because I wanted to investigate it, get closer, understand it better. What spurred the violence was not social status: often it was rich kids fighting each other. I also did not feel that these fights happened out of boredom or out of criminal intent. There was no political motive, there was no class struggle, there was no horizon beyond these attacks.

Was it frustration, pride, insecurity, the desire to join the pack? Yes, in part. But not exclusively.

Writing about violence has allowed me to recognize the emptiness that often fuels it, especially among the young. A darkness, a closed room. Often there are no real reasons, no concrete explanations, just an empty space that cannot be resolved, that cannot be filled.

I have felt that emptiness too, that terrible frustration. Yet, as a young woman, I always felt that violence was something I was not allowed to dish out, something that did not belong to me, something I could only witness or suffer personally. But there are violent teen girls who radiate a monstrous force. When I saw them in action – as children pulling each other’s hair, as adults slapping each other’s faces – I thought they were bold but also wicked. They would not be forgiven for their violence: they would forever be considered unpredictable, ambiguous, at a remove from their prescribed role. That’s why writing about a violent young girl can be liberating, giving her the power to surprise everyone, to be unexpected and terrifying, a shadow that cannot be grasped.

Every violent act leads to another, and as violence escalates it becomes less and less comprehensible, closer and closer to emptiness.”

In Italy, there is an ongoing conversation about violence against women – femicides happen every day and seem impossible to prevent – and in novels, as authors of this generation, we vent the anger that society does not allow us to shout out. This is why my antagonist Gaia, an unassuming red-haired girl with knock-knees, can become fearsome. No longer just a victim of malicious glances and harassing gestures, she becomes someone who knows how to strike out and hurt, who knows how to take revenge. Rage simmers beneath the surface, even for young girls, and writing can embody this, comprehend its existence. Writing succeeds in doing something incredible: it overrides judgement and morality and dives into action: feeling and understanding the electric, frightening energy of bodies in motion. Young female bodies are indeed bombs ready to explode, to risk anything, to self-sabotage. They are bodies so full of hormones, so full of desire that it is not possible to contain them, even as society tries very hard to put them in a cage. And when their desires are not fulfilled, those bodies approach their limits and test their proximity to death.

In addition to this freedom from constraint and artifice, writing can do still more: it can fall in love with violence, absorb it and put it on the page with the force of shooting an arrow or firing a gun.

When Gaia uses a tennis racket to bloody the knee of her tormentor it gives her satisfaction, in which the reader is complicit. But as seductive as that violence may be, can we always justify it? Every violent act leads to another, and as violence escalates it becomes less and less comprehensible, closer and closer to emptiness. Are we sure, as readers, especially female readers, that the empathy we feel when reading a scene of aggression does not say something about our own deep desire for violence?

What I know is that seeing young men frequently hitting and pushing each other has left a deep impression on me, laying the foundations for a style of writing that has made violence its constant companion.

Published in agreement with MalaTesta Literary Agency, Milan

agenziamalatesta.com

—

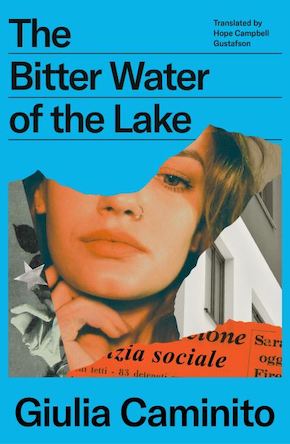

Giulia Caminito’s first novel, The Big A, won the Bagutta Opera Prima Prize, the Berto Prize, and the Brancati Giovani Prize. Also the author of The Day Will Come and Amatissime, her books have been translated in over 20 countries and sold over 150,000 copies. She lives in Rome. The Bitter Water of the Lake won the 2021 Campiello Prize and was a finalist for the Strega Prize. Now translated by Hope Campbell Gustafson, it is published in paperback and eBook by The Indigo Press.

Read more and buy the book

instagram.com/caminits/

instagram.com/theindigopress/

@PressIndigoThe

Author photo by Luca di Benedetto

Hope Campbell Gustafson’s previous book-length translations include Commander of the River by Ubah Cristina Ali Farah and Islands – New Islands by Marco Lodoli. She lives in Brooklyn.

hopecampbellgustafson.com