Waiting on the shelf

by Brett MarieWhen my wife and I married fourteen years ago, our two bookcases became one. It was a lopsided union. Roxanne had cultivated her book collection for years, saving everything she read, all the way back to a desiccated hardcover anthology of Czech short stories she’d liberated from her public library in high school. I, on the other hand, had left my piles of Piers Anthony novels and rock biographies in my boyhood bedroom when I moved to New York, and had blown my meagre wages in the two years since on battered Harmony guitars, Greyhound bus trips and scalped Rolling Stones tickets. Cultured reader that I claim to be, I could only buttress her rows of Milan Kundera and Jean-Paul Sartre with a mass-market paperback of Moby-Dick, Tom Perrotta’s The Wishbones and a small stack of newer rock bios I’d gathered from the shelves of Coliseum Books and the Strand Bookstore.

In the years since Perrotta and Sartre were joined in holy matrimony, I’ve more than once taken advantage of the privileges of marriage, and plucked one of Roxanne’s titles from our shared shelf. Thanks to her, I’m no longer lying when I nod casually and tell you that, yeah, of course I’ve read The Bell Jar, and if you ask me what I thought of The Unbearable Lightness of Being, I can now shrug and say “Meh” with authority.

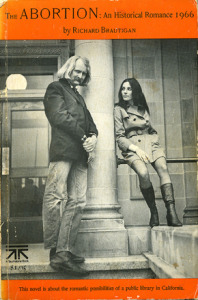

The Abortion: An Historical Romance 1966 first edition, Simon & Schuster, 1971

But the real joy of this literary dowry became apparent when I sampled The Abortion. Reading in awe as author Richard Brautigan took the depressing, controversial topic of the novel’s title and spun from it a whimsical flight of fancy, I marvelled that no one had ever mentioned this genius to me before. Dawn Powell was the next forgotten titan to burst into my consciousness, dazzling me with her deft satire and sharp wit, and painting a New York cityscape more recognisable to me than any of her contemporaries had managed.

Roxanne smiled, and her eyes widened, when I wondered aloud how Dawn Powell had failed to make the faintest ping on my radar until now. “Isn’t she great?” she said. There was a sense of vindication in her voice. But her reaction to my conversion to Brautiganism surprised me: “Oh, I bought that one because of the cover. I haven’t gotten around to it yet.”

Mark Twain famously defined the word ‘classic’ as “a book people praise and don’t read.” We need look only as far as his own Adventures of Huckleberry Finn to prove him wrong, of course – most of us have read that one, and can legitimately give it the praise it deserves. But there seems to be a massive repository of books out there which fit Twain’s description, novels which might have garnered critical accolades or solid sales on first release, but which for some reason couldn’t muster the alchemical energy needed to sear themselves into the literary canon. Browse the shelves at your local used book store; you might be shocked at how much cover space is used quoting raves from The Times or the Guardian on ancient editions of novels you’ve never seen before. Pick one up to read, and your jaw might drop at the thought that it’s had to languish for so long, between half a dozen Robert Langdon novels and half a dozen more copies of Fifty Shades, before Fate finally saw fit to bring you to it, to correct your sin of omission.

Dalton Trumbo knew all about the pitfall of poor timing: Johnny Got His Gun arrived on US shelves in 1939 to warn readers against the horrifying futility of war two days after Adolf Hitler invaded Poland.”

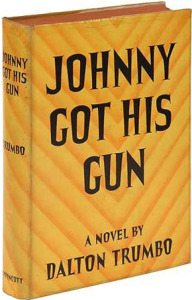

It seems unfair to me that a book should need to be anything more than well-written to achieve classic status. But the sad truth is that it doesn’t stand a chance if it isn’t well-promoted – or well-timed. Dalton Trumbo knew all about the pitfall of poor timing: his Johnny Got His Gun arrived on US shelves in 1939 to warn readers against the horrifying futility of war. Adolf Hitler must have had it in for Trumbo; he invaded Poland two days before the book’s release. As the Second World War began, Trumbo watched in dismay as fascist sympathisers in his country looked to his book for arguments against American involvement in a war effort he supported. He eventually found himself agreeing with his publisher’s decision to pull the title, and within a few short years of its release, Johnny was effectively dead and buried.

Johnny Got His Gun first edition, J.B. Lippincott, 1939

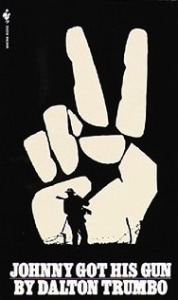

But as long as a work still physically exists, there’s hope for it, and a great work can creep back up on us in any number of ways. Johnny found its way back into currency when the stars realigned on the anti-war movement at the close of the 1960s. Sadly, an army of veterans wounded in Vietnam could suddenly identify with Johnny‘s hideously maimed protagonist. Led by wheelchair-bound US-Marine-turned-pacifist-icon Ron Kovic, these new activists exhumed the novel to promote the cause of peace. A powerful story, expertly told, Johnny needed only this late boost to wedge itself back into the public consciousness, where it remains to this day.

The new film Trumbo (released in the UK on 5 February) has mined Dalton Trumbo’s life and screenwriting career for Oscar ore. I found it surprising to learn that the movie ignores the saga of Johnny Got His Gun. Surprising but not shocking: Trumbo’s principled stand against the House Un-American Activities Committee as a member of the Hollywood Ten (for which he endured blacklisting and an eleven-month prison sentence), will forever dominate any evaluation of the man’s life. That story is rife with drama, and offers us a left-wing hero and free-speech martyr as its star. With source material like that, the film has tremendous potential. But if Dalton Trumbo himself were alive to see it, I’m sure he’d be disappointed at what the film overlooks. During a 1971 interview with Roger Ebert about the movie adaptation of Johnny – a movie he wrote and directed himself – Trumbo called the novel “obviously the best thing I’ve ever done maybe the one good thing I’ve done.” At that time, Trumbo was witness to the resurgence of his favourite work, and was seeing first-hand the galvanising effect his words were having on supporters of his anti-war cause. I can only imagine the pride he must have felt as a writer, to have a piece he wrote make such a direct difference in the lives of other people. And so, just as it’s a shame that Johnny was ignored for so long during Trumbo’s life, I’m sure he’d find it a pity that his important work as an artist is so completely overshadowed by his more camera-ready life as a man.

Bantam mass-market edition, 1984

Of course, as ignored as it is on-screen, in life Johnny Got His Gun won’t go away anytime soon. I found it in a bookstore display in late 2003, six months into a war that had already begun churning out a new generation of Johnnys. A year or two later, a new edition would hit the shelves with a foreword by Cindy Sheehan, the mother of a soldier killed in that war. The book will always be there, waiting on the shelf, to come off again and again, every time we march our children off to the tune of ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’ or ‘God Save the Queen’. If only someday it could have its revival before we strike up the band, it will really have done its job.

It’s become common for publishers to dig up an underappreciated gem and place it on a pedestal in a new edition. Following the decades-late but hugely successful revivals of Revolutionary Road and Stoner, these days the literary spotlight regularly falls on a new-old sleeper novel with comeback potential. Call it the industry’s way of putting things right. Johnny Got His Gun had a more organic revival, but the outcome was the same. With Johnny a fixture on my shelf, I can come back to a great work and remind myself why I love it. And I can thrust my copy at my friends and tell them, “You need to read this book.” Until I do that, it will sit in my lawfully-wedded bookcase, nestled snugly between June Thomson’s Portrait of Lilith and Alec Waugh’s Guy Renton – two other works which may well be great, but which I just haven’t gotten around to yet.

Brett Marie, also known as Mat Treiber, grew up in Montreal with an American father and a British mother and currently lives in Herefordshire. His short stories such as ‘Sex Education’, ‘The Squeegee Man’ and ‘Black Dress’ and other works have appeared in publications including The New Plains Review, The Impressment Gang and Bookanista, where he is a contributing editor. He recently completed his first novel The Upsetter Blog.

Brett Marie, also known as Mat Treiber, grew up in Montreal with an American father and a British mother and currently lives in Herefordshire. His short stories such as ‘Sex Education’, ‘The Squeegee Man’ and ‘Black Dress’ and other works have appeared in publications including The New Plains Review, The Impressment Gang and Bookanista, where he is a contributing editor. He recently completed his first novel The Upsetter Blog.

Facebook: Brett Marie

@brettmarie1979