Waiting for a story

by Wyl Menmuir

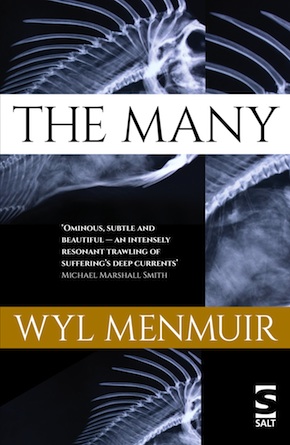

“An intensely resonant trawling of suffering’s deep currents.” Michael Marshall Smith

In April 1999, my flatmates had scattered on extended holidays to the far reaches of the world and I stayed behind in the rancid maisonette flat we shared in a Newcastle suburb. During the day, I rattled around in my dressing gown and kept the curtains closed, resisting the temptation to go outside into what was shaping up to be a glorious spring. When I emerged occasionally for beer and bread, I felt pale even compared to the most milk-faced of Geordies.

Inspired by one of my lecturers, who had once shut himself away in a hotel room in Bangkok for four months to write a detective novel, I had resolved to write a novel myself. I felt I ought to be able to. After all, I’d been writing poetry, lyrics and short stories for as long as I could remember and was now studying for a degree in English Literature and writing for the university newspaper. In my mind I was already a fully-formed novelist, albeit one who just happened not to have written a novel yet. I even toyed with the idea of smoking opium to help my creative flow (I had been reading a lot of De Quincey and Coleridge). A friend agreed to procure some for me, though when she told me as an aside to our conversation, “You know what I’m buying for you, essentially, is smack, don’t you?” I chickened out and returned to the darkened flat, where I lay on the sofa and stared at the watermarks on the walls and waited for inspiration to arrive.

I’d like to say I rattled off 50,000 words that week I stayed on, but the truth is I barely put pen to paper, and when I did, I was too self-conscious to read back what I’d written. Every start I made seemed to lead to a dead end of obvious self-indulgence or poor imitation. From what I remember, the novel was going to be based loosely on the experiences of another of my lecturers, who, during the height of the Cold War, had smuggled religious icons out of Czechoslovakia. Even now, I think the story might have legs. But it remained stubbornly unwritten and my playing at being a novelist just led to a vicious malaise.

This first novel-writing attempt came to an end when I locked myself out of the flat on one of my beer and bread trips and got my head stuck in the bathroom window while standing on the top rung of a neighbour’s ladder trying to break back in. Unwilling to kick the front door down, I abandoned both the flat and the novel and returned to my parents’ home.

This story is one at which I needed to throw everything I had, every piece of feedback and useful advice I’d received, every genius novel I’ve read, every lyric I wrote for bands, and every poem and story I wrote before I started.”

After university, I followed a string of jobs, all of which allowed me to write in one form or another – working on local newspapers, music blogs, magazines and websites, teaching. And though the thought of writing a novel returned every now and then, I realised in that first attempt I had nothing to say that would justify me adding to the thousands of books published that each year add to the burden of the shelves of charity bookshops across the country, or which end up interred beneath motorways the length of the country.

It was twelve years later, sat in a somewhat more well-kept house on the outskirts of London, in the aftermath of trauma, that I decided I was going to start again. The second time round there was no self-imposed exile; I took all the help I could get my hands on. Once I’d committed to writing the novel, I booked myself onto a week’s residential writing course at the Arvon Foundation’s Totleigh Barton, signed up for the online MA in Creative Writing at MMU and registered for the writing app Write-Track. Each helped me in a slightly different way.

At Arvon, I developed the seed of what would become the novel, the core from which the whole story would develop. The two course tutors – Nikita Lalwani and Sam North – helped to manoeuvre me into a place where I could take that creative leap to write fiction about something incredibly painful and real, something worth writing and, more importantly, something worth reading. Write-Track provided the discipline I needed, the prod everyone who’s ever been a journalist needs. MMU gave me, in the form of the support of my course mates and my tutor (now editor) Nicholas Royle, the encouragement to continue, to take risks, and to explore new possibilities for the shape and structure of the narrative. And that’s not to mention the friends who gave up time to read early drafts. Looking back, I can see it took a dizzying amount of support.

Of course, the thinking and the writing could only be done by me. The long walks churning over the next steps. The hours sat on the beach staring out at sea, waiting for the next part of the story to make itself clear. The late nights after the kids were in bed, writing my self-imposed amount of 500 words a day (so far from the creative torrent of words I’d expected the first time round) or reading and rereading what I’d written, of cutting, editing and rewriting. But the support I received around those moments were the things that made it happen.

And this time round it mattered. It mattered because this story is one at which I needed to throw everything I had, every piece of feedback and useful advice I’d received, every sentence I’d written in every article from my first book reviews on the Newcastle Courier onward, every genius novel I’ve read, every lyric I wrote for bands, and every poem and story I wrote before I started The Many.

My Byronic idea of shutting myself away, consuming copious drugs and emerging some point later with a fully formed novel might not have led to the results I wanted, but I’ve realised all the time I’ve been writing, whatever form that has taken, I was just waiting for the right story to tell.

Wyl Menmuir was born in 1979 in Stockport. He lives on the north coast of Cornwall with his wife and two children and works as a freelance editor and literacy consultant. When he’s not writing, you’ll find him out on the water or up on the cliffs – anywhere there’s a view of the sea. The Many, his first novel, is published by Salt. Read more.

Wyl Menmuir was born in 1979 in Stockport. He lives on the north coast of Cornwall with his wife and two children and works as a freelance editor and literacy consultant. When he’s not writing, you’ll find him out on the water or up on the cliffs – anywhere there’s a view of the sea. The Many, his first novel, is published by Salt. Read more.

facebook.com/wylmenmuirauthor

@Wylmenmuir

Author portrait © Dave Muir