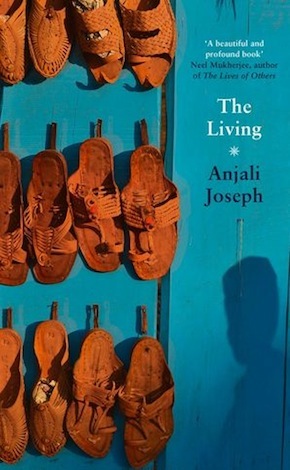

Wet cement

by Anjali Joseph

“A beautiful and profound book.” Neel Mukherjee

Last week I was in Itanagar, the capital of Arunachal Pradesh, a state in the northeast of India that most Indians are, much of the time, only dimly aware of. It’s nearer China than it is to Delhi. I was lucky enough to be there as a jury member for a festival of films from the northeastern states of India.

A couple of days into the festival I was sitting at a table with one old friend, one new mutual friend. Director Nicholas Kharkongor, the new friend, was saying he wanted to move back to the northeast (his heritage is Khasi and Ao Naga). “Maybe for at least three years or so, to make a film,” he said. “Hm,” I mused, “that sounds like about enough time to fit in a disastrous love affair.”

“Oh, but those just happen anyway, na?’ murmured our mutual old friend Pacu, the director of the festival.

Later that night, or early the next morning, the three of us had gone to someone’s house for a late drink and were picking our way back, variously tipsy and sleepy, along a road in the process of being resurfaced. We tottered along wet cement, sometimes all holding hands, giggling. I was more or less sure at least one of us would fall face down into the cement, creating a semi-permanent work of art, like stray dogs whose footsteps live on in tarmac. Between the time we’d gone out for the evening and the end of the dinner, the political crisis in Arunachal had ended; central-government-imposed President’s rule had ended, and the soldiers were off the streets. Itanagar was quiet. There’d been a change of guard.

But, reader, at this point you must be muttering, Stop telling me about your tedious personal life. Talk about books! (This, by the way, is why I like you so much. I’ve lost count of the number of people I’ve met recently – not filmmakers, who do read copiously, but film watchers, who only watch stuff and, in many cases, quasi-virtuously, in the way you might imagine a vegan eyeing you and saying, “I just can’t imagine eating a dead animal” – who say, “Oh, I just can’t read books, somehow.”)

I do have a point though. Honest… After Itangar, I spent a night in Guwahati at the flat I still rent, hanging out with my two best friends, Lueit and Pratyush. We spent hours, much of the night, sitting on the pavement outside Pratyush’s house, even breaking into song. There was no reason why we couldn’t have crossed the road and sat in my apartment, except that Pratyush was about to go up to have a family dinner, and the pavement was an oddly hospitable and undemanding space. Cycle rickshaws passed, and the odd car. Uzan Bazar (an old and famously eccentric locality of Guwahati) was quiet. We looked up at the moon, a golden disc of mica. Two mornings later, I was back in my parents’ apartment in Pune, feeling oddly emotional. So many moments, so many friends, old and new. I looked around and found a song I’d been listening to on and off for years, the American folk singer Josh Ritter’s Dylanesque ‘New Lover’. The narrator of the song tells his ex-girlfriend that he has a new lover now, he hopes she does too… he enumerates, bittersweet, all the differences between them, and ends by saying that although he hopes she does have a new boyfriend, “if you are sad and you are lonesome and you’ve got nobody true/I’d be lying if I said that didn’t make me happy too.” The last line made me laugh and nod as usual. I first heard the song when a then-boyfriend played it to me; subsequently, I remember listening to it during various differently (but similarly) disastrous attachments, in England, in Shanghai, anywhere really. In the end, the feelings that the song carried, and its ability to take me through a certain emotional trajectory had stayed for longer than any specific association. That is one of the things art does: provides the forms that carry us through seas of personal trouble.

A short novel doesn’t feel obliged to give you all the background. It can be peremptory with the authority of hindsight, even with the gaze of infinity. How much, after all, does anything matter? “

In that sense, I think some of the short novels I love have points in common with the songs that have recurred in my life, even with the small but oddly transformative moments I don’t forget, like picking my way through wet cement at three in the morning in Itanagar. In short novels, much has to be omitted. What is left, therefore, becomes radiant. I once translated the whole of Françoise Sagan’s La Chamade for a boyfriend. It was a labour of love, but also a slightly ambiguous gesture. The novel (which I think is about sixty thousand words long) goes through a year in the lives of two characters, a young man and woman. When they meet, both are with other people. They fall in love, begin an affair, leave their partners… and break up. After all that intensity? one feels, reading it. But that’s sort of the point. Perhaps the things that last are not characterised by the usual pageant of cacophony and breakage that passion brings. Or maybe I’m just getting older. I don’t feel it though – I feel younger, less knowing, and more vulnerable by the hour.

A short novel doesn’t feel obliged to give you all the background. It can be peremptory with the authority of hindsight, even with the gaze of infinity. How much, after all, does anything matter? And yet we keep hurting people; we keep getting hurt; it’s difficult to let go. The short novel is at home with that conflict.

I know many readers, and many publishers too feel some unease about short novels. Are they novellas? Are they really novels? Shouldn’t a novel promise to be with you, if not forever, at least for a good five hundred pages? Shouldn’t it become encyclopaediac, shouldn’t it envelop you, shouldn’t it embrace you with its sheer length? Shouldn’t it make you feel secure? Ah, I’m not so sure. So many short novels, I think, come straight out of that melting point between our desire for permanence and our awareness of loss, not as a singular and unfortunate tragedy but just as part of the everyday experience of being human. If I think of some of the other short novels I’ve loved – John Steinbeck’s Tortilla Flat, for example, or V.S. Naipaul’s Miguel Street – it’s that awareness of the beauty of life, the possibility of nobility, and the characters’ just repeating themselves anyway that characterise their mood. In this sense those novels are more honest about people than some sprawling bildungsroman in which a character self-transforms. Or, to borrow from a letter by Samuel Beckett, writing about his then girlfriend, a Frenchwoman named Suzanne Deschevaux-Dumesnil, with whom (after a fashion) he’d spend the rest of his life: “Both of us know it must end. And so there is no telling how long it may last.” I may be the only person I know who thinks this is romantic. It’s not that I don’t long for permanence too – only that I’ve begun to feel it could probably only be achieved with someone else who was also aware, like a Warner Brothers cartoon character, of having run a little bit too fast, and looking down to notice himself, or both of us, hanging above an abyss.

In short novels – Yasunari Kawabata’s Beauty and Sadness, or Amit Chaudhuri’s A Strange and Sublime Address, or Afternoon Raag – the writer leaves space, leaves out much of the furniture of everyday life. The reader gains some space too – space to live in between chapters, space to think about the novel long after finishing it, to plot a re-reading, even, briefly, to look at her or his own life with some of the elegance and irony invited by an awareness of shape. There has never been anywhere to go, it turns out – but it’s still time to set off, maybe, tentatively, amusedly, holding hands with your friends, late in the night, avoiding (just for now) the wet cement.

Anjali Joseph was born in Bombay in 1978 and read English at Trinity College, Cambridge. Her first novel, Saraswati Park (2010), won the Desmond Elliott Prize, the Betty Trask Prize and India’s Vodafone Crossword Book Award for Fiction. Her second novel Another Country was published in 2012. The Living is published by Fourth Estate.

Anjali Joseph was born in Bombay in 1978 and read English at Trinity College, Cambridge. Her first novel, Saraswati Park (2010), won the Desmond Elliott Prize, the Betty Trask Prize and India’s Vodafone Crossword Book Award for Fiction. Her second novel Another Country was published in 2012. The Living is published by Fourth Estate.

Read more.

anjalijoseph.com

@anjalijosephbot

Author portrait © CJ Humphries