Landing a whopper

by Jerome K. JeromeI knew a young man once, he was a most conscientious fellow, and, when he took to fly-fishing, he determined never to exaggerate his hauls by more than twenty-five per cent.

‘When I have caught forty fish,’ said he, ‘then I will tell people that I have caught fifty, and so on. But I will not lie any more than that, because it is sinful to lie.’

But the twenty-five per cent plan did not work well at all. He never was able to use it. The greatest number of fish he ever caught in one day was three, and you can’t add twenty-five per cent to three – at least, not in fish.

So he increased his percentage to thirty-three-and-a-third; but that, again, was awkward, when he had only caught one or two; so, to simplify matters, he made up his mind to just double the quantity.

He stuck to this arrangement for a couple of months, and then he grew dissatisfied with it. Nobody believed him when he told them that he only doubled, and he, therefore, gained no credit that way whatever, while his moderation put him at a disadvantage among the other anglers. When he had really caught three small fish, and said he had caught six, it used to make him quite jealous to hear a man, whom he knew for a fact had only caught one, going about telling people he had landed two dozen.

So, eventually, he made one final arrangement with himself, which he has religiously held to ever since, and that was to count each fish that he caught as ten, and to assume ten to begin with. For example, if he did not catch any fish at all, then he said he had caught ten fish – you could never catch less than ten fish by his system; that was the foundation of it. Then, if by any chance he really did catch one fish, he called it twenty, while two fish would count thirty, three forty, and so on.

You will be nearly sure to meet one or two old rod-men, sipping their toddy there, and they will tell you enough fishy stories, in half an hour, to give you indigestion for a month.”

It is a simple and easily worked plan, and there has been some talk lately of its being made use of by the angling fraternity in general. Indeed, the Committee of the Thames Angler’s Association did recommend its adoption about two years ago, but some of the older members opposed it. They said they would consider the idea if the number were doubled, and each fish counted as twenty.

If ever you have an evening to spare, up the river, I should advise you to drop into one of the little village inns, and take a seat in the tap-room. You will be nearly sure to meet one or two old rod-men, sipping their toddy there, and they will tell you enough fishy stories, in half an hour, to give you indigestion for a month.

George and I – I don’t know what had become of Harris; he had gone out and had a shave, early in the afternoon, and had then come back and spent full forty minutes in pipeclaying his shoes, we had not seen him since – George and I, therefore, and the dog, left to ourselves, went for a walk to Wallingford on the second evening, and, coming home, we called in at a little river-side inn, for a rest, and other things.

We went into the parlour and sat down. There was an old fellow there, smoking a long clay pipe, and we naturally began chatting.

He told us that it had been a fine day today, and we told him that it had been a fine day yesterday, and then we all told each other that we thought it would be a fine day tomorrow; and George said the crops seemed to be coming up nicely.

After that it came out, somehow or other, that we were strangers in the neighbourhood, and that we were going away the next morning.

Then a pause ensued in the conversation, during which our eyes wandered round the room. They finally rested upon a dusty old glass-case, fixed very high up above the chimney-piece, and containing a trout. It rather fascinated me, that trout; it was such a monstrous fish. In fact, at first glance, I thought it was a cod.

‘Ah!’ said the old gentleman, following the direction of my gaze, ‘fine fellow that, ain’t he?’

‘Quite uncommon,’ I murmured; and George asked the old man how much he thought it weighed.

‘Eighteen pounds six ounces,’ said our friend, rising and taking down his coat. ‘Yes,’ he continued, ‘it wur sixteen year ago, come the third o’ next month, that I landed him. I caught him just below the bridge with a minnow. They told me he wur in the river, and I said I’d have him, and so I did. You don’t see many fish that size about here now, I’m thinking. Good-night, gentlemen, good-night.’

And out he went, and left us alone.

We could not take our eyes off the fish after that. It really was a remarkably fine fish. We were still looking at it, when the local carrier, who had just stopped at the inn, came to the door of the room with a pot of beer in his hand, and he also looked at the fish.

‘Good-sized trout, that,’ said George, turning round to him.

‘Ah! you may well say that, sir,’ replied the man; and then, after a pull at his beer, he added, ‘Maybe you wasn’t here, sir, when that fish was caught?’

‘No,’ we told him. We were strangers in the neighbourhood.

‘Ah!’ said the carrier, ‘then, of course, how should you? It was nearly five years ago that I caught that trout.’

‘Oh! was it you who caught it, then?’ said I.

‘Yes, sir,’ replied the genial old fellow. ‘I caught him just below the lock – leastways, what was the lock then – one Friday afternoon; and the remarkable thing about it is that I caught him with a fly. I’d gone out pike fishing, bless you, never thinking of a trout, and when I saw that whopper on the end of my line, blest if it didn’t quite take me aback. Well, you see, he weighed twenty-six pound. Good-night, gentlemen, good-night.’

Five minutes afterwards, a third man came in, and described how he had caught it early one morning, with bleak; and then he left, and a stolid, solemn-looking, middle-aged individual came in, and sat down over by the window.

None of us spoke for a while; but, at length, George turned to the new comer, and said:

‘I beg your pardon, I hope you will forgive the liberty that we – perfect strangers in the neighbourhood – are taking, but my friend here and myself would be so much obliged if you would tell us how you caught that trout up there.’

‘Why, who told you I caught that trout!’ was the surprised query.

We said that nobody had told us so, but somehow or other we felt instinctively that it was he who had done it.

‘Well, it’s a most remarkable thing – most remarkable,’ answered the stolid stranger, laughing; ‘because, as a matter of fact, you are quite right. I did catch it. But fancy your guessing it like that. Dear me, it’s really a most remarkable thing.’

Ha! ha! ha! Well, that is good,’ said the honest old fellow, laughing heartily. ‘Yes, they are the sort to give it me, to put up in my parlour, if they had caught it, they are! Ha! ha! ha!’”

And then he went on, and told us how it had taken him half an hour to land it, and how it had broken his rod. He said he had weighed it carefully when he reached home, and it had turned the scale at thirty-four pounds.

He went in his turn, and when he was gone, the landlord came in to us. We told him the various histories we had heard about his trout, and he was immensely amused, and we all laughed very heartily.

‘Fancy Jim Bates and Joe Muggles and Mr Jones and old Billy Maunders all telling you that they had caught it. Ha! ha! ha! Well, that is good,’ said the honest old fellow, laughing heartily. ‘Yes, they are the sort to give it me, to put up in my parlour, if they had caught it, they are! Ha! ha! ha!’

And then he told us the real history of the fish. It seemed that he had caught it himself, years ago, when he was quite a lad; not by any art or skill, but by that unaccountable luck that appears to always wait upon a boy when he plays the wag from school, and goes out fishing on a sunny afternoon, with a bit of string tied on to the end of a tree.

He said that bringing home that trout had saved him from a whacking, and that even his schoolmaster had said it was worth the rule-of-three and practice put together.

He was called out of the room at this point, and George and I again turned our gaze upon the fish.

It really was a most astonishing trout. The more we looked at it, the more we marvelled at it.

It excited George so much that he climbed up on the back of a chair to get a better view of it.

And then the chair slipped, and George clutched wildly at the trout-case to save himself, and down it came with a crash, George and the chair on top of it.

‘You haven’t injured the fish, have you?’ I cried in alarm, rushing up.

‘I hope not,’ said George, rising cautiously and looking about.

But he had. That trout lay shattered into a thousand fragments – I say a thousand, but they may have only been nine hundred. I did not count them.

We thought it strange and unaccountable that a stuffed trout should break up into little pieces like that.

And so it would have been strange and unaccountable, if it had been a stuffed trout, but it was not.

That trout was plaster-of-Paris.

From Three Men in a Boat (1889), excerpted from A Twitch Upon the Thread: Writers on Fishing, introduced and edited by Jon Day (Notting Hill Editions, £14.99)

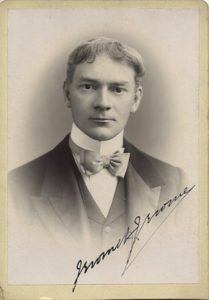

Jerome Klapka Jerome (1859–1927) was born in Walsall and brought up in East London. He left school at fourteen and worked as a railway clerk, actor, journalist and teacher. In 1885 he published On the Stage – and Off, which was followed in 1886 by Idle Thoughts of an Idle Fellow. In 1888 he married Georgina Stanley and a year later he published his most famous work, Three Men in a Boat, which has remained in print ever since. The sequel, Three Men on the Bummel, appeared in 1900. Jerome also wrote several other novels, plays, stories and autobiographical writings, edited The Idler and Today magazines and, during the First World War, worked for the French ambulance service.

Jerome Klapka Jerome (1859–1927) was born in Walsall and brought up in East London. He left school at fourteen and worked as a railway clerk, actor, journalist and teacher. In 1885 he published On the Stage – and Off, which was followed in 1886 by Idle Thoughts of an Idle Fellow. In 1888 he married Georgina Stanley and a year later he published his most famous work, Three Men in a Boat, which has remained in print ever since. The sequel, Three Men on the Bummel, appeared in 1900. Jerome also wrote several other novels, plays, stories and autobiographical writings, edited The Idler and Today magazines and, during the First World War, worked for the French ambulance service.

jeromekjerome.com

Jon Day is a writer, academic, cyclist and fisherman. He worked as a bicycle courier in London for several years, and now teaches English Literature at King’s College London. His essays and reviews have appeared in the London Review of Books, The Times Literary Supplement, n+1, and the Guardian. He writes about art for Apollo, is a regular book critic for the Financial Times and The Telegraph, and a contributing editor of The Junket. A Twitch Upon the Thread and his memoir Cyclogeography (2015) are both published by Notting Hill Editions. He is also teh author of Homing (John Murray, June 2019), about living with pigeons.

Jon Day is a writer, academic, cyclist and fisherman. He worked as a bicycle courier in London for several years, and now teaches English Literature at King’s College London. His essays and reviews have appeared in the London Review of Books, The Times Literary Supplement, n+1, and the Guardian. He writes about art for Apollo, is a regular book critic for the Financial Times and The Telegraph, and a contributing editor of The Junket. A Twitch Upon the Thread and his memoir Cyclogeography (2015) are both published by Notting Hill Editions. He is also teh author of Homing (John Murray, June 2019), about living with pigeons.

A Twitch Upon the Thread

Cyclogeography

Homing

@NottingHillEds

Author portrait © Mark Cocksedge