Wise parables and meaningful tales

by Mika Provata-CarloneSpecific leitmotifs dominate any attempt to weave together a narrative of the history of Romania and Hungary during the Second World War: the complex, troubled, vital historical background of the Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman empires, and the emergent territorial claims of the Soviet Union; the cultural, ethnic and demographic tessellation of the region; the inalienable plexus of destinies, and the desperate yearning for national discreteness and sovereignty; the politics of central European fascism and irredentism, the fluctuations of neutrality and chameleonic coalitions, of isolationism and belonging, of ghettos and communities; the biography and genealogy of racial hatred; the power of local folklore, landscapes, the bloodlines of archetypes. The destinies of peoples and the particular drama of the Jews.

Romania lays claim to a personal record of horror: it sent more soldiers to support Operation Barbarossa than all the other German allies put together; according to the Final Report of the International Commission on the Holocaust in Romania, “Of all the allies of Nazi Germany, it bears responsibility for the deaths of more Jews than any country other than Germany itself.” Arguably, Hungary does not lag very far behind: although a late starter in the history of the Holocaust (Hungarian Jews have the terrible distinction of being the ‘Last Victims’ of the Nazis’ extermination programme), by the time the Germans occupied the country, in March 1944, it would provide the setting, under the supervision of Adolf Eichmann, for a final, horrendous ‘blitz-cleansing’. According to the historical records, within barely three months, there would be almost no Hungarian Jews left, except for a few in Budapest.

For the small city (town, really) of Sighet, the interlaced, bitterly antagonistic fates of Hungary and Romania would produce an ever-alternating state of constant tension, suspension and corrosive friction. For its very substantial, deeply rooted Jewish population, they would signify near total annihilation. Sighet was Hungarian until 1918, Romanian after the Treaty of Trianon in 1920; yet again under Hungarian rule after 1940, following the Second Vienna Award, once more Romanian after the end of the Second World War. The tribulations of its geopolitics became a foil to the martyrdom of its Jews, a historical mise en scène for a new set of unsurvivable human tragedies and stories, to be added to the lore and legends of the land.

Elie Wiesel’s trilogy, Night, Dawn, Day is one of the starkest acts of confrontation with history, with our expectations for or our betrayal of our own humanity, even with God.”

Few were left to pick up the narrative threads and tatters of extraordinary communal presence, of savage persecution, of inconceivably brutal annihilation. Inconceivably, and yet minutely, determinedly, purposefully planned, to its very last horrific detail. One of those who sought to find the words to chronicle these lives lost, the histories that were destroyed, to retrace the places where such rich presence and such total erasure took place, was Elie Wiesel. His trilogy, Night, Dawn, Day is one of the starkest acts of confrontation with history, with our expectations for or our betrayal of our own humanity, even with God. Wiesel called the first part, Night, a “deposition”: this is a trial of our own right to existence – an interrogation of the substance and essence of human nature. As Wiesel writes, during the Holocaust, and as a Survivor, he “was the accuser. God the accused.” What happened was not only the persecution of a people; it was an execution of Creation and its Creator – “Where is God now? … Here He is – He is hanging here on this gallows…”

For those like Naomi Seidman, who see our engagement with history, dark or light, as a sacred duty, a true mitzvah, Wiesel’s Night transformed “the Holocaust into a religious-theological event”; for Wiesel, it is precisely this duty to engage the I and the Thou, with clear responsiveness and responsibility, that lies at the heart of his storytelling – that makes literature after Auschwitz possible. It is a pilgrimage to understand, confront the rage and despair, the disgust with self and dehumanised humanity, the guilt and guiltlessness of survival, the complicity of those who did not act, “the world [who] remained silent.” Wiesel’s deposition and testimony has defined in an inalienable way the way we should stand before history – the way we should examine our historical conscience and memory, our own part within it. Yet another voice and narrative would also emerge from that same small town of Sighet, parallel and auxiliary to Wiesel’s, even if less known: that of Yoseph Leib (Leibi) Arye Ludovic Bruckstein. The relationship between Wiesel and Bruckstein is one of momentous and eerie synchronicity – a dance of shadows between two blazing, very different lights, commemorating the same event: the passions and resurrection of our humanity.

Bruckstein and Wiesel were both born to great historic Hassidic families, where wisdom was venerated and stories were sacred; they were both deported to, and survived, Auschwitz. Bruckstein’s camp ID was A37013, and he would say that perhaps 13 was his lucky number. Wiesel’s was A7713, yet he did not see the same symbolic power in the last two digits. Both would become writers after the war, seeking in words both the past and the future, the redemption of material being, and the reconfirmation of transcendence. Both would be pronounced “spiritual leader[s] and guide[s]”, maggidim communicating sacred truths and human stories in a world seemingly abandoned by both men and gods. Wiesel famously left for Paris, where he followed the lectures of Jean-Paul Sartre and Martin Buber, reading Dostoevsky, Kafka and Thomas Mann. His stories of the history of the Holocaust are existential dramas of conscience, they evince the critical momentum of a consciousness burningly alert to every raw moment, to each primordial howl. They are documents of death and life, experienced without a shred of compromise.

If Wiesel was an educator of souls and minds, Bruckstein would be a keeper of stories, dreams and pains… endowed with a metaphysics of vernacular, quotidian, yet timeless experience.”

Bruckstein, on the other hand, stayed for several decades in Romania, becoming a journalist and playwright; his unpoliticisable ethics and discourse would make him yet again an undesirable, and the communists would wipe him out of official literary history. He eventually succeeded in making aliyah to Israel in the early ’70s with his wife and son, where he continued to write, also becoming a publisher. He would call his publishing house the Panopticon Press – a home for books that could contain the many visions and sides that make up even a single life. The difference in places of settlement or displacement between Wiesel and Bruckstein engender also seminally contrasting perceptions, expressions, ways of engagement – or disengagement. If Wiesel was an educator of souls and minds, Bruckstein would be a keeper of stories, dreams and pains. He too has teachings to deliver, firmly rooted and embodied in their human element, endowed with a metaphysics of vernacular, quotidian, yet timeless experience.

His posthumously published The Trap is a poignant distillation of his style, his presence, his organic relationship with the voices of an entire tradition that resonates with distinctly modern clarity. The eponymous novella has a gripping, breathless orality, a folktale immediacy of darkly ironic humour that echoes uncannily Bella Chagall’s own memoirs, Burning Lights and First Encounter, their intimacy and legacy of community here transfused with the deathly testimony of the Shoah. The question of God, His agency and oversight on human destiny, His will over human fate, are a dominant theme, an expression of both strength and despair, a powerful, theological analysis of being and non-existence through the gestures of simple humanity, a daring challenge to all denial of trauma or survival.

Bruckstein too leaves behind an indelible witness account of what will always be there, for all the efforts to exterminate a people, history, their material or spiritual imprint on the world’s soul and on time.”

Where Bella Chagall beguiles with the longing of the everyday, the timeless rituals of Jewish life, Bruckstein haunts with the brutal assault against these same, parallel Jewish lives in his native Hungarian Romanian Sighet. He too leaves behind an indelible witness account of what will always be there, for all the efforts to exterminate a people, history, their material or spiritual imprint on the world’s soul and on time. Bella Chagall’s books were oneirically illustrated by Marc Chagall, and Bruckstein’s too feature the semiotically ghostly ink drawings of his son Freddy. Bella tells the story of Jewish happiness, Bruckstein that of Jewish woe, yet both speak of an inexhaustible, unbreakable humanity.

The two novellas in The Trap are set in “a kingdom without a king, where reigned a kind of admiral regent without a fleet, and without a sea, an admiral who liked always to be photographed riding a white horse. An equestrian navy.” We are in the realm where myth and reality clash and feed on each other, where the uncanny, the surreal and the inescapably factual collapse into a single experience that demolishes every limit of reason or even of conceivable possibilities of existence. It is an out-of-mind and out-of-body experience, an audacious use of folklore motifs and narrative tropes, which allows for a uniquely powerful prism: of what ought to be the utter absurdity of horror, the total inconceivability of violence and destruction, for any truly human mind. Ernst, a young Jew accused of bearing an Aryan name, of having studied architecture in Vienna, knows that he is a marked man as soon as the Germans arrive in Sighet: he has been singled out by another young man with beautiful hands, a German officer who studied art history in Berlin. Their resemblance, at least in type, makes him a target of discriminatory hatred: how dare he not seem the Other he must supposedly be? This is 1944, and some news has perhaps travelled fast. Ernst decides to flee to the mountains, hide, escape what he knows is bound to happen. From a shepherd’s house, he observes the activities in the small town down in the valley, as though he were looking at the comings and goings of ants in an anthill. It is a chilling and bold use of irony, defamiliarisation, parable and multiple focal points, which expose the atrocious surreality of Nazism, without ever removing, obscuring or silencing the hellish, actual reality of its conscious and intentional evil.

The question of the survival of one single individual when millions perish, that key moral question in Wiesel, is here framed very differently, yet with the same anguish and pain, evoking the rustic pictoriality and biblical mythography of Marc Chagall’s paintings. Only the ancient traditional forms that have survived for centuries, Bruckstein seems to say, can themselves endure the unspeakable stories they must now convey and contain. History, as it happens, in its every detail, is mediated to Ernst by the shepherd in whose house he has found shelter, Ionu Stan, the “Son of the Trustworthy One”. The latter becomes an extraordinary agent of inactive witnessing, of passive complicity, a mordant way for Bruckstein to say that it was never a neutral, impersonalised ‘they’ who brought the Nazi regime into absolute power, or who made their actions possible, who normalised them and socially integrated them. It is an embodiment of Buber’s I-and-Thou that cuts to the bone, a plea to humanity, but also a clear and eponymous attribution of causation and blame.

‘The Trap’ is quick-paced, moving in and out of the real, and what ought to have been surreal and hallucinatory, yet came to be so materially, appallingly, concrete. It is a tale of tragedy, of false hopes, a sobering lesson that “evil does not happen elsewhere” but right here, and one can very seldom avoid being scathed by what happens at arm’s length. The end is a triumph of contre-plongée irony, a political comment whose quiet formulation belies its ominousness. As the Soviet Army moves in and the Germans flee, Ernst rejoices at the thought of liberation, survival, hope. Instead, he is summarily rounded up to make up for the number of Nazi prisoners required by the Russian military authorities. Ernst the Jewish architect and the young art historian from Berlin who sought to exterminate him are now both united in a new historical nightmare. One not so dissimilar, Bruckstein seems to say, from the one that had apparently just ended.

The dead end, or terrible cyclicity of ‘The Trap’, the unflinching questioning of truths and falsehoods is given wider berth in the second novella ‘The Rag Doll’, a longer story where factual events and self-delusion are now at play. It is as though the parable-like form of ‘The Trap’ were a preamble to a more closely realistic anatomy of the progression from good to evil, from humanity to dehumanisation, from everyday communal existence, to hallucinatory horror: “like in a film unreeling not in slow motion, so that you can see every single frame, or at normal speed, the same as in everyday life, but faster and faster, with everything happening before you have time to realise when and how it happened.”

‘The Rag Doll’ examines not only the process to destruction, but also the efforts at reconstruction, the yearning for a moment and a time beyond. It gives voice to memory, to constitutional oblivion, to the renunciation of oneself, to the silence, which can be some of the most traumatic aspects of survival. Once again, the I and the Thou stand side by side, are made to face each other, perhaps even retrieve a common ground: “Whence did such creatures arise? What kind of parents raised them? What kind of school educated them?” asks Hannah, the main character (and owner of the rag doll), of the Nazis. Hannah survives, like Ernst, by hiding, a concealment that persists even after the war is over. Things have and have not changed, after all. It is a concealment that is also an erasure, and ‘The Rag Doll’ is a story of recovery, of resurfacing, essentially of return to roots and homelands through acts of both severing and retrieval, through the remembrance of Old Testament parables about “Cities destroyed, but not forgotten, cities now rebuilt, which would last forever and ever through the power of love and mutual understanding.” It offers an aliyah to the world of both the living and the dead.

The Trap was written at the end of Bruckstein’s life, as he was dying of cancer. It is a final tribute to what must never be forgotten, a literary text that draws both on powerful originality and the sempiternal structures and motifs of a long and living tradition. It has a voice that knows it will soon be an echo, and therefore speaks not to capture the reader’s interest, but to evoke the common rhythms, the symbols and codes that make us truly and together human. Beautifully translated, it resonates with old worlds and new homelands, with remembrance and beginnings. With lives lost, and, one would hope, lives regained. To be read listening to Tchaikovsky’s piano trio…

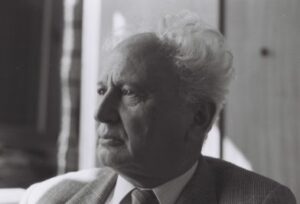

Ludovic Bruckstein in Israel, 1987 © Rita Bruckstein

Ludovic Bruckstein was born in 1920, in Munkacs, then in Czechoslovakia, now in Ukraine, and grew up in Sighet, a small town in the district of Maramureș in the Northern region of Transylvania. He wrote a number of successful plays including The Night Shift (Nacht-Shicht, 1947), based on the Sonder-kommando revolt in Auschwitz. His other works include the novel The Confession (1973), and the story collections The Destiny of Yaakov Maggid (1975), Three Histories (1977), The Tinfoil Halo (1979), As in Heaven, So on Earth (1981), Maybe Even Happiness (1985) and The Murmur of Water (1987). The Trap (two novellas) appeared posthumously in 1989, and is published in English translation by Alistair Ian Blyth by Istros Books, together with the story collection With An Unopened Umbrella in the Pouring Rain.

Read more

@Istros_books

Alistair Ian Blyth is one of the most active translators working from Romanian into English today. A native of Sunderland, he has lived for many years in Bucharest. His translations from Romanian include Little Fingers by Filip Florian, Our Circus Presents by Lucian Dan Teodorovici, Coming From an Off-Key Time by Bogdan Suceavă and Life Begins on Friday by Ioana Pârvulescu (Istros Books, 2020).

Mika Provata-Carlone is an independent scholar, translator, editor and illustrator, and a contributing editor to Bookanista. She has a doctorate from Princeton University and lives and works in London.

bookanista.com/author/mika/

Read the story ‘The Secret Mission’ from the collection With An Unopened Umbrella in the Pouring Rain

Read the story ‘The Secret Mission’ from the collection With An Unopened Umbrella in the Pouring Rain