Witching with ink

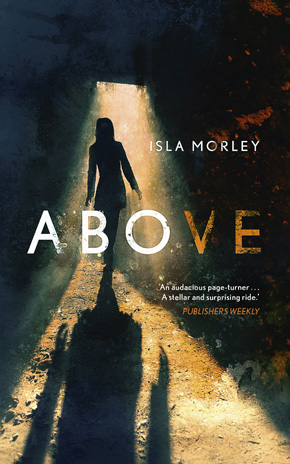

by Isla MorleyWith very few exceptions, books about writing are nuts-and-bolts manuals. They should be kept with the recipe books and IKEA furniture assembly instructions. The idea is that if you follow the steps, apply logic and put in the hours, you will construct something as substantial as a house. Do these three things sufficiently well, and you can put a for-sale sign out front. Luck, magic or karma will have nothing to do with getting a buyer. Don’t get me wrong – how-to books are loaded with practical stuff relating to the Inciting Incident, Point of View and keeping the narrative arc from looking like a bent straw. It’s just that for me, writing is more like witchcraft than driving rivets. With both my first novel, Come Sunday, and second, Above, I didn’t set out to write a story. Rather, I came under a spell.

Where particles had arranged to form a chair, a patch of worn oak flooring and shaft of afternoon light was suddenly a configuration not earthly enough to touch but not sufficiently imagined to dismiss. A woman, bereft. So bereft, in fact, that my curiosity turned morbid, the way it might do at a crash scene. Had I known better, I’d have looked away. As soon as she sensed me looking, the spectre turned her sad, stillborn stare at me. She might have sliced the air with her hand. How she did it, I’m still not sure, but suddenly I was sitting in an office chair, my fingers furled around a pen, the edge of my desk a place looking nothing like home.

With every story, it is the same. I sit before the empty page no longer an unbeliever, but a ready initiate at a séance. When I pick up the pen, I might as well be moving a wooden cursor around a Ouija board. It all feels pointless and silly, until it doesn’t. Until the spectre steps out again from between the atoms and sticks her pointy finger in my side or whispers her paraffin breath in my ear. So mechanically does my hand move that it might as well belong to an automaton. With little effort, ink pools into images. I am a well-behaved mother of I can’t be sure how many children all of a sudden, the wife of a man whose name is on the tip of my tongue, and I’m not at all sure how I got into a nuclear missile silo or what the emaciated girl in the dark is doing with a knife. In equal measures, I am fairly certain I shouldn’t be here and fairly certain I should.

Be careful if you write. They are not your friends, those who appear. Even though you will spend more time with them than with your children, you will cheer the day they leave.”

Others come up out of their graves or step between overlapping dimensions. They slip in through the cracks in plaster, from under the crawlspace. They show up, and it is impossible to look away. Some have skins as thick as carapaces, others no skin at all. The man with the clip-on tie and carefully combed hair is locking a girl away, and given to me is not only how he hides her, but why he does.

Be careful if you write. They are not your friends, those who appear. Even though you will spend more time with them than with your children, you will cheer the day they leave. You will be under their spell no more. You will be rid of them (or they rid of you). It’s not at all true that you will miss them. You will slam shut all the notebooks. Any trace of them will be packed away in cardboard boxes and put up on the rafters. You might rearrange your office so your desk won’t face that portal again. You might even have to choose another place to conduct your business. You might vow never to go near an empty page again. You might be in the mood to put your computer in the driveway and back over it with a Land Rover.

For a while, you will be inclined to go outside, as people do. You will try to recall the names of flowering shrubs. You will remember to add to the grocery list something you have been meaning to buy for months. Laundry detergent. You will be able to keep track of whose birthday is coming up. You will marvel at how efficient the brain is at keeping the chequebook balanced and praying for the friend of a friend who is about to die. So efficient now that it doesn’t have to be worrying about the beautiful trapped girl two hundred feet underground.

And then this happens: you start to feel just a teeny bit abandoned, just a teeny bit un-special, invisible, anonymous. You’d do well to consider the facts: bewitched on the good days, sure, but held underwater on the bad. It hadn’t been all incantations and out-of-body experiences. Many hours were a slog strung between too-many-to-justify tea breaks. There’d been huge holes to fix, a beginning that started sixty waffly pages in, and two endings. There’d been fifteen thousand precious words shaved off in one rewrite, and twenty thousand added in another. Set the record straight: it wasn’t all taking dictation from the Oracle.

If I were a sensible person, I’d go one step further. I’d get a get a real job, or learn to graft roses or write recipe books. But instead, I’m looking into empty corners again. Quite cavalierly, I’ve sprawled out empty notepads. Packs of pens are tucked in places like emergency cigarette packs by someone trying to quit smoking. Though I write about what is unseen, here is the truth of it: the process of writing makes me feel seen. It matters not one iota if the one who turns her gaze on me is a phantom.

Isla Morley grew up in South Africa during apartheid. Now in the Los Angeles area, she shares a home with her husband, daughter, a cat, two dogs and four tortoises. Come Sunday, her debut novel, was awarded the Janet Heidinger Prize for Fiction, was a finalist for the Commonwealth Prize and was longlisted for the Sunday Times Literary Award. Above is published by Hodder & Stoughton in paperback and eBook. Read more.

Isla Morley grew up in South Africa during apartheid. Now in the Los Angeles area, she shares a home with her husband, daughter, a cat, two dogs and four tortoises. Come Sunday, her debut novel, was awarded the Janet Heidinger Prize for Fiction, was a finalist for the Commonwealth Prize and was longlisted for the Sunday Times Literary Award. Above is published by Hodder & Stoughton in paperback and eBook. Read more.

islamorley.com

Author portrait © Molly Hawkey