All the women I ever imagined

by Sabahattin AliI had been in Germany for almost a year by now. One dark and rainy day in November – how clearly I remember it – I was skimming the newspaper when I noticed an article about an exhibition of new painters. In truth, I did not know what to make of this new generation. Perhaps I didn’t like them because their work was too bold, and going to any lengths to catch the eye. I found that mode of self-promotion alien and distasteful. And so I passed over this article without bothering to read it. But a few hours later I was out on my daily stroll through the city when I happened to find myself standing in front of the building where that exhibition was being held. I had no pressing business. So I took a chance and stepped inside. Slowly I wandered through the exhibition, surveying the paintings, large and small, with no little indifference.

Most of them made me want to laugh: there were people with cubic shoulders and knees and heads and breasts of disproportionate sizes, and landscapes portrayed in stark colours, made of something like crepe paper. Crystal vases as shapeless as the shards of broken bricks, flowers as lifeless as if they had been pressed inside books for many years, and finally these dreadful portraits that looked like the sketches of criminals… Yet the visitors were enjoying themselves. Perhaps I should have dismissed these artists for presuming they could achieve great height from such little effort. But when I considered the twisted pleasure they might gain from being punished and ridiculed, I could only pity them.

She wore a strange, formidable, haughty and almost wild expression, one that I had never seen before on a woman… I couldn’t help but feel that I had seen her many times before. “

Four generations of Sabahattin Ali’s family: his grandmother, mother, sister, wife Aliye and daughter Filiz. Edremit, 1938, courtesy Filiz Ali

Suddenly, near the door to the main room, I stopped. Even now, after all these years, I cannot describe the torrent that swept through me in that moment. I only remember standing, transfixed, before a portrait of a woman wearing a fur coat. Others pushed past me, impatient to see the rest of the exhibition, but I could not move. What was it about that portrait? I know that words alone will not suffice. All I can say is that she wore a strange, formidable, haughty and almost wild expression, one that I had never seen before on a woman. But while that face was utterly new to me, I couldn’t help but feel that I had seen her many times before. Surely I knew this pale face, this dark brown hair, this dark brow, these dark eyes that spoke of eternal anguish and resolve. I had known that woman since I’d opened my first book at the age of seven – since I’d started, at the age of five, to dream. I saw in her echoes of Halit Ziya Uşaklıgil’s Nihal, Vecihi Bey’s Mehcure, and Cavalier Buridan’s beloved. I saw the Cleopatra I had come to know in history books, and Muhammad’s mother, Amine Hatun, of whom I had dreamed while listening to the Mevlit prayers. She was a swirling blend of all the women I had ever imagined. Dressed in the pelt of a wildcat, she was mostly in shadow, but for a sliver of a pale white neck, and an oval face was turned slightly to the left. Her dark eyes were lost in thought, absently staring into the distance, drawing on a last wisp of hope as she searched for something that she was almost certain she would never find. Yet mixed in with the sadness was a sort of challenge. It was as if she were saying, “Yes, I know. I won’t find what I’m looking for… and what of it?” The same challenge was playing on her plump lips. The lower lip was slightly fuller. Her eyelids were somewhat swollen. Her eyebrows were neither thick nor thin but short. The dark-brown hair that framed her broad forehead fell down over her cheeks, and her fur coat. Her pointed chin was slightly upturned. Her nose was long, her nostrils flared.

My hands were almost trembling as I flipped through the exhibition catalogue. I was hoping I might find out more about the painting. At the bottom of a page at the very end, I found just three words beside the number of the painting: Maria Puder, Selbstporträt. Nothing else. Clearly the artist had no other work in the exhibition. I was not unhappy about that. I was afraid her other paintings might not have the same overwhelming effect on me and indeed diminish my initial admiration. I stayed until late. Occasionally I got up and wandered through the gallery, looking blindly at the other paintings, but soon I came back to the same place to gaze at that one painting. Each time it seemed as if I could see new expressions in her face, as if she were slowly coming to life. Her downcast eyes seemed to be glancing at me and her lips, I thought, were fluttering.

With time, the gallery emptied out. The tall man at the door must, I thought, be waiting for me to leave. Quickly I stood up and left. A soft rain was falling over the city. For once, I made straight for the pension without dawdling along the way. I was desperate to get through dinner and retire to my room, to conjure up the image of that face.

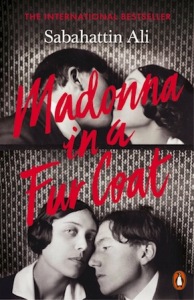

Extracted from Madonna in a Fur Coat, translated by Maureen Freely and Alexander Dawe, published by Penguin Classics

Sabahattin Ali (1907–1948) is recognised by many as the father of Modernist Turkish Literature and a resistance icon. A dedicated socialist, he owned and edited a popular weekly newspaper called Marco Pasha, which became a target of government censorship during the 1940s because of its satirical editorials criticising President Kemal Atatürk’s policies. Ali was imprisoned twice for his controversial writing, and killed under suspicious circumstances on the Bulgarian border as he attempted to leave Turkey. It is widely believed he was murdered by the National Security Services, and his belongings were never returned to his family.

Madonna in a Fur Coat was originally published in 1943 and has now been translated into 17 languages. It has been a bestseller in Turkey since its re-release in 2013, selling over 750,000 copies. Maureen Freely and Alexander Dawe’s translation is out now in paperback from Penguin Classics.

Read more.

Maureen Freely grew up in Turkey and is an author, journalist and award-winning translator. She is the current President of English PEN. Alexander Dawe is an American translator based in Istanbul.