‘Yellow Peril’

by Kathryn Hughes

Amongst the many novelties of the 1871 Crystal Palace cat show were two Siamese cats, which ‘are said to be the first of the kind ever brought to this country’. Owned by a Mr Maxwell, about whom little is known, the animals were described by one journalist as ‘singular and elegant, in their smooth skins and ears tipped in ebony, and blue eyes with red pupils’.

The mention of ‘red pupils’ is slightly alarming. Did the cats have an eye infection (very possible given the haphazard hygiene at the early cat shows), or was something else in play? Another writer who caught an early sight of the Siamese cats provides a clue: having described the newcomers neutrally as ‘soft fawn-coloured creatures with jet black legs’, he then goes on to rail at them as ‘an unnatural nightmare kind of cat’. With their angled faces, ‘bat-like’ ears, and close-cropped fur which showed off a lean, lithe skeleton, these creatures looked like nothing on earth. Specifically, they looked nothing like the fluffy, baby-faced cats in adjacent cages who now dominated the English cat fancy. Siamese cats, by contrast, appeared to have been stitched together from the leftover bits of other animals. Either that, or they were goblins.

In fact, Mr Maxwell’s were not the first of these ‘nightmare’ creatures to arrive in Britain. Since the 1840s there had been a trickle of ‘Royal Siamese’ into the country – the Duke of Wellington had managed to get hold of one, and other high-ranking military men and diplomats had received similar gifts from King Mongkut of Siam, who was keen to be on good terms with Britain. These cats were the equivalent of an exquisite silk shawl or a teak ornament, part of a gift economy that had smoothed international diplomacy for centuries.

That didn’t mean, though, that either Mongkut, or his son and successor King Chulalongkorn, were profligate with their animal favours. Writing in 1889 Harrison Weir quoted Hubert Young, a pioneering cat breeder from Harrogate, who reported: ‘I have heard a little more regarding the Siamese cats from Miss Walker, the daughter of General Walker, who brought over one male and three females.’ Young went on to explain: ‘It seems the only pure breed is kept at the King of Siam’s palace, and the cats are very difficult to procure, for in Siam, it took three different gentlemen of great influence, three months before they could get any.’

Far from Edward Gould receiving the Siamese cats from the king as an exquisite gift, he had bought them from a street vendor for 3 baht.”

Difficult, but not impossible, if you knew the right people. A few months after the appearance of Mr Maxwell’s cats at Crystal Palace, Lady Dorothy Nevill exhibited her Siamese, ‘Mrs Poodles’. Formidably well connected, Nevill had obtained Mrs Poodles directly from the Siamese court, thanks to Sir Robert Herbert of the Colonial Office. Over the next ten years a trickle of Siamese appeared at Crystal Palace until, in 1885, Miss Lilian Gould scooped a prize with a pair that had been brought back by her brother, consul to the court of Bangkok. Years later Miss Gould revealed that, far from Edward Gould receiving the Siamese cats from the king as an exquisite gift, he had bought them from a street vendor for 3 baht. All the romantic chatter about ‘The Royal Siamese Cat’ being in the exclusive gift of a jealous king needed to be taken with a pinch of salt.

Even so, there was no denying that Siamese cats had endured a glacially slow take-off in Britain. Going back through old catalogues, Harrison Weir counted only fifteen females and four males exhibited at Crystal Palace between 1871 and 1887. That was less than one a year. Quite apart from the difficulty of getting hold of these creatures, there remained the question of why anyone would want to. To those cat fanciers who aimed to make a profit, it made no sense to cultivate a novelty breed in which there was some interest but little demand. Too many imponderables remained to be settled before these creatures could be fully embraced by the British cat fancy.

For one thing, were they even cats? Harrison Weir had not helped matters when he described them as being the same colour as ‘Himalayan rabbits’, prompting people to wonder whether they were actually a high-altitude bunny. One know-it-all who attended an early show at Crystal Palace explained loudly that Siamese cats were the result of breeding cats and dogs together to produce a hybrid. On another occasion visitors were disappointed when a particularly skittish ‘Siamese cat’ turned out to be a possum. Another person, who was acting as a guide at the show, assured a visitor that Siamese cats were so-called because they were conjoined, like Chang and Eng Bunker, the twin brothers from Siam who had toured throughout Europe and America twenty years earlier.

Assuming you accepted that Siamese cats were cats, with one head, four legs and a full set of internal organs apiece, there was still the issue of how they fitted into existing NCC taxonomies. According to a long-standing distinction in the British cat fancy, short-haired cats were ‘British’ or ‘Domestic’, while long-haired ones – Persians, Angora, Russians – were always ‘Foreign’ or ‘Oriental’. But the Siamese cat breached these distinctions in spectacular fashion: not only were they obviously ‘Oriental’ but their fur was equally obviously short. For this reason, they attracted the interest of more scientific cat fanciers, including Lady Dorothy Nevill, and Lilian Gould (later Mrs Veley) who had studied biology at Oxford and had a particular interest in how colour is passed from generation to generation.

Lurking behind these descriptions of the Siamese cat as hailing from the borders of the known world lay a potent set of fears and fantasies. Anglophone readers had not yet forgotten the preposterous work of Mrs Anna Leonowens, author of The English Governess at the Siamese Court (1870). It is clear now that Leonowens exaggerated the role she played during her six-year sojourn in Bangkok. She wasn’t there as a governess, but simply to teach King Mongkut’s wives and children English – the emerging lingua franca of global modernity.

According to her telling, the king and his entourage were bare-chested semi-savages with an attitude to sex that bordered on the animalistic.”

Still, that didn’t stop Anna Leonowens portraying the Siamese court as a brothel with a side-serving of titillating barbarism. According to her telling, the king and his entourage were bare-chested semi-savages with an attitude to sex that bordered on the animalistic: His Majesty unblushingly reveals to ‘Mrs Anna’ that he has eighty-two children by thirty-two wives. A tang of sadism hangs heavy in the air: rebellious concubines get flung into dungeons and traitors are put to death in thrillingly ingenious ways. The book was a sensation, propelling Leonowens to international celebrity. Her sequel, published three years later, was called simply The Romance of the Harem.

The Siamese court was understandably appalled at the way it had been traduced by Mrs Leonowens. Plenty of people pointed out that King Mongkut had spent nearly thirty years as a Buddhist monk while waiting to come to the throne and had proved himself a mild, modernising presence well before Mrs Leonowens arrived to point out where he was going wrong. He had tackled the custom of courtiers going bare-chested, deciding that shirts were more dignified. He had released royal concubines from bondage so that they could find their own husbands and he also outlawed forced marriages. Far from being some ‘ignorant savage’, King Mongkut knew perfectly well that the world was round and that Siam occupied a place of great strategic importance within it. That was why he was so keen on everyone learning English.

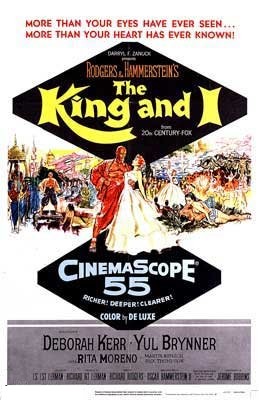

Years later, Mrs Leonowens encountered Mongkut’s successor King Chulalongkorn in London, where he had come to congratulate Queen Victoria on her Diamond Jubilee. As ever, His Majesty was accompanied by his favourite Siamese cat. The king thanked his former language teacher for her service decades earlier but also voiced his dismay at the wild inaccuracies about Siam that she had unleashed on the world. ‘Why did you write such a wicked book about my father King Mongkut?’ he asked. ‘You know that you have made him utterly ridiculous.’ One can only feel grateful that Chulalongkorn did not live long enough to see The King and I, the Rodgers & Hammerstein film musical of Leonowens’s story in which a bare-chested Yul Brynner and a breathless Deborah Kerr polka around a ballroom making eyes at each other while warbling ‘Shall We Dance?’ The movie is banned in Thailand to this day.

The very first Siamese cats arrived in Britain just as Leonowens’s books were landing. Extrapolating from her portrayal of the people of Siam (or rather its male elite) as clever, wilful, egotistic and childish, it was inevitable that the cats would be similarly caricatured. For you couldn’t deny that they were singularly smart, and chatty, quite unlike the general run of British moggies. Siamese cats unhitched latches, opened windows, slipped into food cupboards and, when things didn’t go their way, were not shy about saying so at top volume. Indeed, it was this ability to speak that made them seem unnervingly human. Frances Simpson, who did eventually come to keep Siamese cats herself, grasped how addictive they could become, writing in 1903, ‘ to fanciers of this unique breed other cats must appear lacking in interest and wanting in intelligence’. Her friend, Lady Marcus Beresford, who had her cats straight from the Siamese court, declared them to be ‘dear’ friendly, gentle ‘little people, so clever and attractive’, leaving it unclear as to whether she was talking about the feline or human population of Siam.

One early British expert described imported Siamese kittens as being ‘just like English children brought from abroad’. In other words, not yet acclimatised to their happy destiny as Britons.”

Given that the Siamese cat was identified so strongly with its ‘exotic’ homeland, it is no surprise that its assimilation into British cat culture proved patchy. One early British expert, Mrs A. Hawkins, described imported Siamese kittens as being ‘just like English children brought from abroad’. In other words, not yet acclimatised to their happy destiny as Britons. If you did manage to breed from them, Mrs Hawkins’s advice was to separate newborns from their Siamese birth mother and put them to nurse with a ‘cottage cat’ – a nondescript belonging to the gardener, or someone from the village. In the process, legs would straighten, flanks fatten and any suggestion of the sniffles dry up. Above all, Siamese kittens thus reared would start to take on that stiff upper lip and sturdy self-reliance which had made Britain the ruler of a quarter of the world although not – significantly – of Siam.

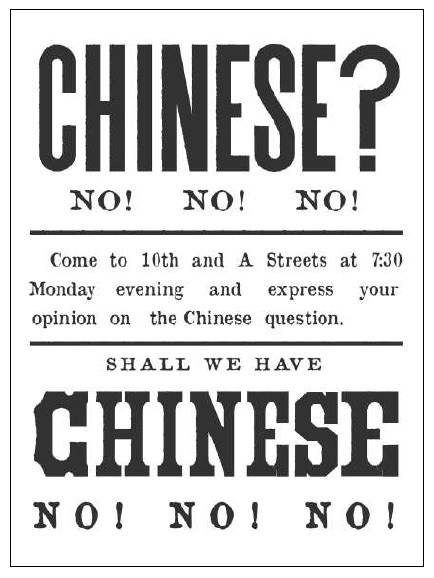

If such acts of assimilation – or colonialisation – were not accomplished, then who knew what might happen. Siamese cats who had failed to transition to a British diet were said to be a martyr to worms, and the thought of these trojan horses spraying a ‘pestilence’ through the British cat community didn’t bear thinking about. In the process a whole set of racial and geopolitical fears were mobilised. Towards the end of the century, the conviction grew that an indistinct ‘swarm of yellow men’ was poised to invade from the East. British influence in China had long been waning and the Boxer Rebellion of 1899–1901, which aimed at expelling Westerners, had revealed just how powerful the Chinese people could be when roused. There were so many of them that all it would take, according to one admiral, was for the people of ‘the Orient’ to ‘walk westwards’ and European civilisation would be trampled underfoot. Even the sober-sided Times warned its readers to prepare for ‘a universal uprising of the yellow race’.

This terror of bodily invasion from the East was whipped into further shapes by the pulp-fiction writer M.P. Shiel. In his best-selling Yellow Danger (1898) Shiel depicts the sinister Dr Yen How, half-Japanese and half-Chinese, who not only has an insane hunger for one particular Englishwoman but also a ravenous desire to destroy every other citizen of Great Britain. It is not too much of a spoiler to add that the doctor fails, although not before displaying fiendish cunning. Yellow Danger was hugely influential, spawning ‘Dr Fu Manchu’, the enduring villain created by Sax Rohmer in 1913 and still going strong in 1965 in the hugely popular and schlocky film portrayal by Christopher Lee in yellowface.

The fact that both Leonowens and Shiel were of mixed ethnic backgrounds (born in India and Monserrat respectively) but pretended otherwise, perhaps explains their fixation with being invaded, taken over, and ‘mastered by foreign bodies’. How ironic, then, to learn that Siam itself was far from being a homogenous country: like any trading nation its population was diverse, consisting of Lao, Khmer, Malays, Mon, Thawai, Yuan, Persians, Portuguese and Chinese, as well as the numerically dominant Thai. The Siamese cat came from a land that was infinitely more varied than anyone in the ‘Occident’ could possibly imagine.

Apart from the classic Royal Cat of Siam there was another strain of almost equal prestige – the Temple Siamese cat, which had a dark brown coat against which the colour points did not stand out. This cat was the type probably belonging to Lady Dorothy Nevill. All the same, you had to be careful not to expand the category of ‘Siamese’ to take in every unfamiliar imp that crossed your path. In 1896 Louis Wain, in his capacity as judge at an NCC show, caused a kerfuffle when he refused to recognise as a Siamese ‘a blue which had been brought home [from Bangkok] by Mr Spearman’. In 1901 the Siamese Cat Society was set up by Lilian Gould, now Mrs Veley, and some other breeders to expand and adjudicate these matters for good.

By the early 1880s the US government had become so alarmed by this seemingly never-ending ‘stream of yellow men’ that it passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, prohibiting further immigration of Chinese labourers.”

When it came to America, the Siamese cat laboured under an even heavier cloud. Its history had started charmingly enough in 1878 when David Sickles, a diplomat at the court of Siam, had sent a cat to the First Lady, Lucy Hayes. ‘I have taken the liberty of forwarding you one of the finest specimens of Siamese cats that I have been able to procure in this country. I am informed that it is the first attempt ever made to send a Siamese cat to America’ (it wasn’t of course). With remarkably little imagination, Mrs Hayes had decided in advance to christen her new pet ‘Siam’ and he immediately lived up to his breed’s reputation for fussiness. The following year, while the first family was away on holiday, Siam fell ill (the breed was known to pine for its owners, further evidence of its ‘childish’ personality). The White House staff tried everything to tempt the tastebuds of the First Cat who had started life in a palace: fish, chicken, duck, cream, even oysters. When that failed, they sent for the president’s personal physician, who prescribed beef tea and milk every three hours. These human remedies were of no use. Siam died just nine months after setting paw in the Land of the Free.

Despite this shaky beginning, or even because of it, you might have expected Siamese cats to start flocking into the upper echelons of the American cat fancy: they were expensive, recherché and, most importantly, had not yet been colonised by the British. Yet, writing in 1903, Frances Simpson reported that ‘the love of Siamese cats has not seemed as yet to have developed in America, and specimens of the breed are few and far between’.

This was because America had its own, more virulent version of the ‘Yellow Peril’. From the 1860s, Chinese workers had been brought in as indentured labourers, or ‘coolies’, to help build the country’s trans-continental railways. By the early 1880s the US government had become so alarmed by this seemingly never-ending ‘stream of yellow men’ that it passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, prohibiting further immigration of Chinese labourers. This law, or something very like it, remained in place until the Second World War.

Fears and anxieties about peoples from ‘the East’, especially Siam, lingered far into the twentieth century. Walt Disney’s 1955 full-length animation Lady and the Tramp features twin Siamese cats, drawn with huge piercing blue eyes and buck teeth. Singing in sinister sibilants, and double-dubbed by Peggy Lee, ‘Si’ and ‘Am’ move with synchronised precision, as if joined at the hip. Motivated solely by acquisitive malignity, they stalk through their Park Avenue mansion making cannibalistic mischief as they try to gobble up the caged canary, the goldfish and the baby’s milk. Given half a chance they would probably eat the baby too. When their owner ‘Aunt Sarah’ comes to investigate the cause of the ruckus, Si and Am turn hysterical, kicking their legs in the air like tantruming toddlers and putting the blame on good-as-gold heroine, the doe-eyed spaniel ‘Lady’.

‘The Siamese Cat Song’ not only terrified generations, but for decades afterwards was adopted as an ugly playground taunt directed at people of Asian heritage. It caused deep offence among Japanese Americans too, many of whom had been interned during the Second World War. They were quick to spot the clumsy transposition in which Si and Am come to stand in for a stock villain from the Far East (the Vietnam war began five months after the film’s opening night). In the 2019 remake of Lady and the Tramp, the sequence with the Siamese cats has been dropped and replaced by a number called ‘What a Shame’.

from Catland: Feline Enchantment and the Making of the Modern World (Fourth Estate, £22)

—

Kathryn Hughes was educated at Oxford University and holds a PhD in Victorian studies. She is a visiting lecturer at several British universities and reviews regularly for the Daily Telegraph and the Literary Review. Her previous books are The Victorian Governess, The Short Life and Long Times of Mrs Beeton, George Eliot: The Last Victorian and Victorians Undone. Catland is published by Fourth Estate in hardback, eBook and audio download.

Read more

@4thEstateBooks