In the zone

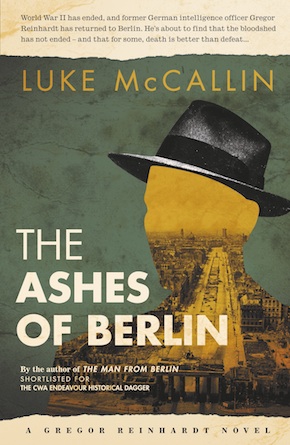

by Luke McCallin

“Let’s not mince words: historical thrillers don’t come any better.” Financial Times

In early 1947, the time in which The Ashes of Berlin is set, the Second World War had been over nearly two years. Although the guns had fallen silent, the war’s effects lingered on, and the peace had thrown up problems all its own.

The main character of the novel, Inspector Gregor Reinhardt, returns to an occupied Berlin. He returns from having been a prisoner of war. He returns to a city he hardly recognises. He returns with baggage from the war. He returns as a former officer of an army so thoroughly defeated there are no words for it. And he returns on the coat-tails of the occupation forces, of the Americans in particular…

Berlin was not only ruined, it was divided. Divided as it was into four sectors, one for each of the victorious Allies, Berlin was a microcosm of the occupation of Germany itself. The country was run by an Allied Control Council supposed to develop and implement policy and issue laws, but there were very different visions for Germany’s future and the role of Germans in it.

The realities of the peace could no longer mask the divisions that the alliance against the Nazis had papered over, and these divisions between the Allies were unfortunate because the tasks facing them were Herculean and demanded cooperation and coordination.

Most of Germany’s cities had been heavily bombed by the British and American air forces. Berlin itself had been shattered by the war and solely occupied by the Red Army from the beginning of May to the beginning of July 1945, when British and American troops entered the city. The city was thoroughly sacked during the Soviet assault, and the population – particularly Berlin’s women – suffered the near-constant depredations of Red Army soldiers in the weeks that followed. Even today, traces of those last battles in April 1945 can be found.

The health and sanitation situation was grave as the country headed into one of the coldest winters in living memory. Diseases such as tuberculosis took virulent root, and there were outbreaks of cholera, typhoid and diphtheria. Rations were insufficient and malnutrition was rife. Researching The Ashes of Berlin, I read about how families were crammed into damaged and insalubrious accommodation. Children went to school hungry, and came home famished. I discovered the stories of the millions of refugees – Poles, Balts, Ukrainians and Jews – who lived in shabby camps, cherishing memories of the homes they had lost and dreaming of the homes they might one day find somewhere else.

The health and sanitation situation was grave as the country headed into one of the coldest winters in living memory. Diseases such as tuberculosis took virulent root, and there were outbreaks of cholera, typhoid and diphtheria. Rations were insufficient and malnutrition was rife. Researching The Ashes of Berlin, I read about how families were crammed into damaged and insalubrious accommodation. Children went to school hungry, and came home famished. I discovered the stories of the millions of refugees – Poles, Balts, Ukrainians and Jews – who lived in shabby camps, cherishing memories of the homes they had lost and dreaming of the homes they might one day find somewhere else.

Basic services such as water and power took time to restore. Law and order and functioning local administration had to be put in place while ensuring neither became refuges for former Nazis. There were millions of displaced people, such as slave labourers and prisoners of war to care for and repatriate, not to mention the dire situation facing most Germans themselves.

There were Nazis to be found, and judged.

All this would have challenged any administration. As it was, and despite the genuine efforts of many Allied officials, the occupation was marked by inefficiencies in administration, vagaries among the zones, often strong degrees of callousness, with corruption a worsening element. Black markets were ubiquitous. People had to adapt. Either that, or they did not survive.

As is so often the case with war and the population displacements that result, the burden of it fell unequally on women and children.”

Many didn’t survive, I discovered. Suicide rates soared, especially among men. What happened to the families they left behind, I wondered, knowing from my humanitarian work that men and women often faced such existential trials in very different ways…?

As is so often the case with war and the population displacements that result, the burden of it fell unequally on women and children. Women and girls were the victims of horrendous levels of sustained sexual violence by the conquering powers, but the fate of their menfolk was playing out to its own drama. A huge percentage of Germany’s men had served in the armed forces and were dead, wounded, missing, or imprisoned. Due to traditional recruitment policies of the German armed forces, many of the survivors of the officer corps were refugees from eastern Germany, from provinces lost to Poland or in the Soviet zone.

As is so often the case with war and the population displacements that result, the burden of it fell unequally on women and children. Women and girls were the victims of horrendous levels of sustained sexual violence by the conquering powers, but the fate of their menfolk was playing out to its own drama. A huge percentage of Germany’s men had served in the armed forces and were dead, wounded, missing, or imprisoned. Due to traditional recruitment policies of the German armed forces, many of the survivors of the officer corps were refugees from eastern Germany, from provinces lost to Poland or in the Soviet zone.

Worsening matters, the Allied Control Council dissolved and declared illegal all German veterans’ organisations, including the armed forces. The law banned any association of veterans and revoked all their pensions, benefits and rights, including from those who had not even fought in the war. At one fell swoop, this rendered all but destitute millions of men and the families who depended upon them. Veterans became widely distrusted and vilified.

With the German armed forces, indeed almost any organisation remotely military in nature rendered illegal, this left the police as the only remnant of the German state capable of exercising control and upholding the law. The police, however, were powerless to prevent crimes committed by the Allies. Furthermore, the police leadership across the country had been replaced with men picked by the Allies for their loyalty. In Berlin, this saw the Soviets replace the entire police force with ‘anti-Fascist’ elements that often behaved as badly as, if not worse than, their Fascist forebears.

Paul Margraff, a German soldier captured at Stalingrad, became Berlin’s chief of police. Margraff unabashedly promulgated pro-Soviet policies, turned a blind eye to Red Army excesses, and ensured Berlin’s police towed the Soviet line. Police officers were complicit in the harassment of non-Communist politicians and parties, and showed little cooperation with the Western Allies. Exasperated by Margraff’s behaviour and the general attitude of Berlin’s police, the Western Allies eventually negotiated a thorough reform in October 1946.

Paul Margraff, a German soldier captured at Stalingrad, became Berlin’s chief of police. Margraff unabashedly promulgated pro-Soviet policies, turned a blind eye to Red Army excesses, and ensured Berlin’s police towed the Soviet line. Police officers were complicit in the harassment of non-Communist politicians and parties, and showed little cooperation with the Western Allies. Exasperated by Margraff’s behaviour and the general attitude of Berlin’s police, the Western Allies eventually negotiated a thorough reform in October 1946.

This reform brought Reinhardt back into the Berlin police.

It brings to a close a story that began in the Balkans, that led Reinhardt from despair to a reawakening to himself, to resistance, and finally to a form of reconciliation – with himself, his city, and with his estranged son, who he thought had vanished on the eastern front.

With war, and its aftermath, it is too easy to be stunned by the glare of violence, the shatter of ruins, and to forget that most people do no harm but they do receive it, and somehow they carry on.”

The path that led from Sarajevo to Berlin was a logical one within the life I had imagined for Reinhardt. But it was in deciding how to get my head around the challenge of writing a novel set in Berlin that was as true as it could be to the realities of an occupied and devastated city, that I realised with Reinhardt I was trying to get to the human aspects of one man caught between choices. And that with war, and its aftermath, it is too easy to be stunned by the glare of violence, the shatter of ruins, and to forget that most people do no harm but they do receive it, and somehow they carry on.

Bringing Reinhardt back to Berlin was closure for that part of his life, and for those times, for which I thought I had things to say about collaboration, resistance, occupation. The time of the Second World War is one that fascinates me, when the fates of individuals – or the ability of individuals to decide their fates – were cast into the fire. We like to think there is not much we cannot control, but in fact the raw edges to life are closer to us than we like to think. Not only that, but a person can be undone and brought to nothing, or worse, can be warped away from who that person might have been.

Bringing Reinhardt back to Berlin was closure for that part of his life, and for those times, for which I thought I had things to say about collaboration, resistance, occupation. The time of the Second World War is one that fascinates me, when the fates of individuals – or the ability of individuals to decide their fates – were cast into the fire. We like to think there is not much we cannot control, but in fact the raw edges to life are closer to us than we like to think. Not only that, but a person can be undone and brought to nothing, or worse, can be warped away from who that person might have been.

There are other things I want to say with Reinhardt now. I want to start a new story, new stories. I’m working on a fourth book, which will show Reinhardt in the trenches. I always wanted to write a WWI book, and with Reinhardt I think I have the right vehicle. We’ll see him as a young man, faced with an investigation in the trenches at a time of utmost turmoil as the war begins to turn definitively away from the Germans, as men’s discipline begins to fray, and the tide of revolution begins to sweep from the east.

All that will begin a new period of research, which is exciting and terrifying at the same time. I’ve noted that WWI is somewhat ‘owned’ by the British, the Australians, the Canadians and New Zealanders when it comes to touring the Western Front. I need to tour the old battlegrounds, but I need to do it from the other side, so to speak, from a German perspective. Who knows how I might see things once – if – I manage that…?

Whatever else it will be, it will be exciting!

Luke McCallin was born in 1972 in Oxford, grew up in Africa, went to school around the world and has worked with the United Nations as a humanitarian relief worker and peacekeeper in the Caucasus, the Sahel and the Balkans. He lives with his wife and two children in an old farmhouse in France in the Jura Mountains. The Ashes of Berlin is published in paperback and eBook by No Exit Press, along with the earlier Gregor Reinhardt novels The Man from Berlin and The Pale House.

Luke McCallin was born in 1972 in Oxford, grew up in Africa, went to school around the world and has worked with the United Nations as a humanitarian relief worker and peacekeeper in the Caucasus, the Sahel and the Balkans. He lives with his wife and two children in an old farmhouse in France in the Jura Mountains. The Ashes of Berlin is published in paperback and eBook by No Exit Press, along with the earlier Gregor Reinhardt novels The Man from Berlin and The Pale House.

Read more

lukemccallin.com

@mccallinluke

Author portrait © Barbara McCallin