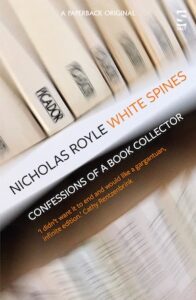

A collector’s thing

by Nicholas RoyleNicholas Royle’s White Spines: Confessions of a Book Collector reflects on the author’s passion for Picador’s fiction and non-fiction publishing from the 1970s to the end of the 1990s. It explores the books themselves, the bookshops and charity shops he gathers them from, and the way a unique collection grew and became a literary obsession. Above all, it’s a love song to books, writers and writing.

Tell us about the bookshelves in your home

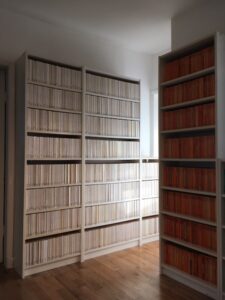

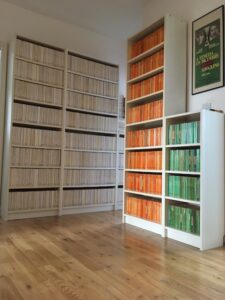

They range from the terrifyingly ordered to the comfortingly chaotic, according to your preference. Picadors are shelved together, but only the white-spined ones published between 1972 and 1999/2000, excluding all ‘anomalies’ as I call them (logo in the wrong orientation, wraparound coloured cover/spine, inset illustration on spine, etc.). So are orange Penguins and green Penguins. Certain other imprints are shelved together – white-spined editions by King Penguin, Abacus, Paladin, Sceptre, etc. – so that walking into my flat is a little like entering Foyles in the 1980s. Elsewhere, things look more conventional, more of a mishmash, but there’s still a kind of order, even if only I would know it.

Which books are your most recent bookshelf additions?

I’ve just come back from Holmfirth Oxfam Bookshop with a lovely copy of La Belle Captive (Cosmos) by Alain Robbe-Grillet and René Magritte, the first copy I’ve seen since the copy I borrowed from the University of London library (and returned) in 1986. On the way home from Holmfirth, I visited George Street Community Bookshop in Glossop and relieved them of an armful of books, including a Picador I’d never seen before, Robert Edric’s The Earth Made of Glass.

Do you judge people by their bookshelves?

I am endlessly fascinated by people’s bookshelves. I form opinions, like anyone else.

Which is your most treasured book?

In December 2017, in Book & Comic Exchange in Notting Hill, I found a copy of my fourth novel, The Director’s Cut (Abacus). When I find second-hand copies of my own books I always have a look inside. On the title page I read, “Thank you*. Nicolas Roeg.” Lower down I found: “* What on earth do I mean? This is a present to me!! NR. It’s BRILLIANT…” I didn’t know what to make of it. Nicolas Roeg is/was my favourite film director. He lived in Notting Hill and was still alive in December 2017 (he died in November the following year). I had given him copies of both editions of the book, since I had hidden the titles of his films in the text. But still, this didn’t quite make sense. It was just someone messing about. I put the book back on the shelf. Later, however, I googled Roeg’s signature. It was the same. It was him. Maybe he felt he didn’t need both editions. I went back the next day and bought it. I hope they were nice to him when he went in. I’d been in a few times selling books in the 1990s. There was a look they gave you. I hope they didn’t give it to him.

What do your bookshelves say about you?

When Miranda Sawyer wrote about my shelves in the Observer in 2015, she described them as colour-coded but, with respect to Miranda, they’re not really. The books are shelved by imprint. She asked me what my system says about me and I answered, “I suppose they say I’m a massive control freak. But I just like a certain degree of order in my life.” Or at least that’s what appeared in print. I can’t remember if I actually said that, but it sounds about right. Maybe what they really say is that I like to impose at least the appearance of order on the terrible and bewildering chaos of the world.

What’s the oldest book on your shelf?

It looks like it might be Volume 1 of The Family Physician: A Manual of Domestic Medicine by Physicians and Surgeons of the Principal London Hospitals, including Sir William Gull. It’s not dated, but online research suggests it dates from 1900.

Maybe what my bookshelves really say is that I like to impose at least the appearance of order on the terrible and bewildering chaos of the world.”

Do you rearrange your bookshelves often – and where do your replaced books go?

I’m forever having to find more shelf space as certain collections expand. I try to make more space by replacing hardbacks with paperback editions, which I realise is a bit pathetic and/or desperate, but, really, who wants hardbacks? Not me, not any more, not if there’s a paperback edition. I do most of my reading walking along and hardbacks are much less convenient for that.

Do you have any books from your childhood on your shelves?

I’ve still got a full set of Squelchers, little booklets about football produced for Esso in 1970, and a full set of Greater Manchester bus timetables, or Bus Guides, as they called them, dated 1976–78. A red hardback book called Insect Life (Winchester Publications) that has my older sister’s name on the half-title page crossed out and my younger sister’s name written in underneath. And a 16-page home-made – well, school-made – book by me called All About Me, with a drawing of me, by me, on the cover. It begins, “My name is Nicholas Royle. I am 5 years old.” There are crayoned unlikenesses of my parents, details about my hands and feet, and a statement that my favourite television programme was Doctor Who. I’ve got lots of Enid Blytons and Hardy Boys books and Three Investigators books and John Gordon’s The Giant Under the Snow in the same editions that I had when I was a child, but in many cases, perhaps all cases, these are copies I’ve reacquired since in a vain attempt to recreate the innocence and blissful happiness of my childhood, the original copies having gone missing, or perhaps migrated to my younger sister’s bookshelves.

Book lender, book giver or book borrower?

I’ve lent out far too many books that I’ve never seen again, so it makes more sense to be a book giver, especially as I keep buying books that I’ve already got. I generally try to avoid borrowing books, as I fear I’ll forget who I’ve borrowed them off and so not know who to give them back to. I’ve got a couple of books that I know are not mine but I can’t remember who gently insisted that I borrow them. One I do know who lent it to me, but he’s disappeared. Or I don’t know where he is or how to get in touch with him. It nags at me every day, the knowledge that this book is not mine.

Whose bookshelves are you most curious about?

When I walk down residential streets, my eye is always drawn to bookshelves half-seen in front rooms. In the front room of a flat across the road from my wife’s flat in Stoke Newington, north London, someone seemed to have created a shelf of Picador books – white-spined B-format paperbacks of some description anyway – and a shelf of black Penguin Classics beneath that. Maybe there was also a shelf of green Penguins. I can’t remember and I can’t find the photograph. Yes, I took a photograph.

Nicholas Royle is the author of seven novels, including Counterparts and First Novel, and four collections of short stories, most recently London Gothic. He teaches at Manchester Metropolitan University and runs Nightjar Press. Series editor of Best British Short Stories, he also edited The Art of the Novel, in which he included a chapter by his namesake, also a novelist and a professor at the University of Sussex. His recent translation of Vincent de Swarte’s novel Pharricide (Cōnfingō Publishing) was chosen as runner-up in the TA First Translation Prize. White Spines is out now in paperback from Salt Publishing.

Nicholas Royle is the author of seven novels, including Counterparts and First Novel, and four collections of short stories, most recently London Gothic. He teaches at Manchester Metropolitan University and runs Nightjar Press. Series editor of Best British Short Stories, he also edited The Art of the Novel, in which he included a chapter by his namesake, also a novelist and a professor at the University of Sussex. His recent translation of Vincent de Swarte’s novel Pharricide (Cōnfingō Publishing) was chosen as runner-up in the TA First Translation Prize. White Spines is out now in paperback from Salt Publishing.

Read more

nicholasroyle.com

@nicholasroyle

@saltpublishing

Nicholas was talking to Mark Reynolds

Click on images below to enlarge and view in slideshow