A dreadful fascination

by Blessin Adams

The true tales of murder that feature in Great and Horrible News cover a period of some 200 years, from approximately 1500 to 1700. It was a time that encompassed the rise and fall of the Houses of the Tudors and the Stuarts, the English Civil War, the Protectorate, the Restoration and the Glorious Revolution. England split from Rome, and the country was torn asunder by the Protestant Reformation and Counter-Reformation. Medieval superstitions began to wane, and secular knowledge flourished through movements such as the Renaissance, the Enlightenment and the Scientific Revolution.

Through these centuries countless wars were waged, plagues ebbed and flowed, the countryside was transformed by enclosure and cities and urban populations grew exponentially. The lives of individual men and women were shaped, sometimes irrevocably so, by the significant events of their time. Yet, first and foremost, this is a book that is interested in the personal, human experiences of everyday people as they confronted death in its most extreme, violent and tragic forms. Through the surviving historical records we can step into crime scenes from hundreds of years ago, examine clues and objects left behind, and hear the voices of victims, families, witnesses and perpetrators as they navigated the crises that had devastated their lives.

Reading about shocking crimes and exercising one’s indignation has long been a popular pastime. True-crime publications in early modern Britain were more than news sheets describing the details of murder; they also sought to provide moral and religious instruction along with occasional, practical advice to fearful citizens who were keen to avoid becoming victims of crime themselves. More than anything, however, the early moderns were drawn to true-crime narratives because they touched upon fears tucked away in the darkest corners of their hearts: these are dreadful events that happen to other people, may they never happen to us.

As an ex-police officer I found the experience of exploring historical records of crime and murder to be strangely familiar. In my old profession I often stood upon the threshold of scenes of sudden, violent and unnatural deaths. Walking into those scenes, I felt myself passing from the role of spectator to active player in the story of a complete stranger’s death. They would never know me, but perhaps I would come to discover a little about them as I entered into their private space, touched their personal effects and inspected their body. On the whole I examined scenes of sudden death through the lens of professional training, but I couldn’t help be moved on a personal level by the remaining artefacts of an everyday life now gone: an unfinished paperback novel on the bedside table, last night’s dishes waiting to be washed up, or a well-worn pair of shoes with the backs flattened by years of hurried use. It was not only the mystery of sudden death that fascinated me, but all the details of life that remained in its wake. Just such artefacts are also present in historical records, and while we shall never know the people written about in those documents we nonetheless can be moved by the small details of their lives that remain after death.

The way in which early modern investigators approached potential crime scenes may strike readers today as being not only forward-thinking but decidedly modern.”

While the mechanisms of law enforcement in the early modern period were ancient, the methods by which murder was investigated were slowly changing, innovating and modernising. Forensic pathology and toxicology were newly emerging sciences, and surgeons, physicians and coroners alike sought not only to identify but to classify the symptoms of death. This was the era that ushered in the Enlightenment and the Scientific Revolution; it was a time of rational thought in which professionals in secular fields held evidence as being superior to belief. It was no small wonder that revolutions of thought in the worlds of science and medicine were to filter down on to the front line of criminal investigation. Some coroners strove to establish logical methodologies as they processed crime scenes, gathered material evidence, examined bodies and questioned witnesses. Those men in the business of law and justice in the early modern period combined good old-fashioned detective work with the innovative ideas coming out of the schools of science and medicine. The way in which early modern investigators approached potential crime scenes may strike readers today as being not only forward-thinking but decidedly modern. Yet progress was a slow process, and many professional bodies were resistant to change. By and large the investigation of murder in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries was intuitive, and successful prosecutions often came down to the intelligence and experience of individual investigators.

—

Stories of murder and mayhem in early modern England often come to us in a piecemeal fashion through print and manuscript records that are fragmentary and faded by time. My research is drawn from a wide range of sources, which include coroners’ inquest records, court documents, pamphlets, newspaper articles, ballads, wills, letters and diaries. Within these records we find fascinating, disturbing and often deeply moving tales of murder as told by those who were personally involved or who bore witness to those events. The stories in this book are true, yet we must remember that they were presented and recorded by individuals and groups who had their own biases, motivations and agendas. Nonetheless, I believe it is important to preserve the voices of the dead, and so when quoting from these sources I have expanded the trickier contractions but otherwise kept the original spelling. One of the agonies in researching crime in this period is that so much of the historical record has not survived. Many records have simply been lost or destroyed, others thrown away in the name of bureaucratic efficiency, a few have been stolen, and many yet remain undiscovered in the dark recesses of archives and libraries. From what small pieces we have, there are to be found amazing stories of the lives and deaths of people that at once seem so distant and yet so familiar.

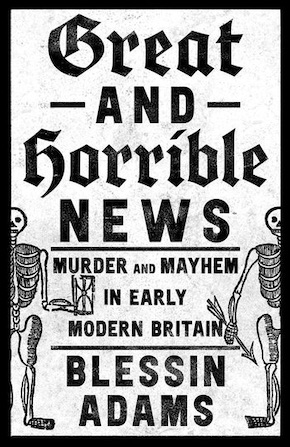

from the introduction to Great and Horrible News (William Collins, £18.99)

—

Blessin Adams traded police work investigating today’s crime in the Norfolk Constabulary for academia, tracing the lives and deaths of people in early modern England. She received her doctorate following research in early modern English law and literature at the University of East Anglia. As a fan of true crime she is fascinated by historical stories of murder and justice. She lives in Norfolk with her husband and two dogs, and is a beekeeper in her spare time. Great and Horrible News, her first book, is published by William Collins in hardback, eBook and audio download.

Read more

blessinadams.com

@adams_blessin

@WmCollinsBooks