A party for Hanna

by Rebecca Wait

“A masterclass in familial tensions, told with razor-sharp dialogue, wit and emotional insight.” Guardian

The first guests start to arrive. There is not yet any sign of Hanna, who claimed she would be there early.

‘But “early” for Hanna still means late by most people’s standards,’ Kemi says. She doesn’t seem at all worried that Hanna might not turn up, so Alice tries not to be either.

She welcomes in a couple of Hanna’s friends from sixth-form college (Alice doesn’t recognize them, though Kemi greets them enthusiastically), and then a woman Hanna worked with at the restaurant before she started in the civil service. Alice is very glad Kemi is there. Kemi smoothly handles these awkward early moments as the first guests are shown into the living room (which now seems cavernous, like an empty cathedral), ensuring everyone has a drink and making some quick introductions.

There is a painful early lull when there are still too few guests and they are all standing looking at each other in the too-large, too-quiet room, but after that everyone starts arriving at once. Alice goes back and forth between the front door and living room, never quite finishing introductions or showing people where they can put their jackets before the bell goes again.

Hanna’s Cambridge friends arrive together, and Alice is relieved to see them; they are the first guests she actually knows, if only a little. It is strange to find yourself at a party full of strangers when you are the host. Alice, truth be told, is rather frightened of parties, and she keeps being astonished afresh to discover herself in the midst of throwing one. But she is doing this for Hanna, she reminds herself, to show Hanna how pleased she is to have her home, and that she wants things to be different between them from now on.

So here is Lavinia, statuesque in black, and curly-haired Santiago coming in behind her, and the slender, pale Lola in a sequined dress. They are slightly unexpected friends for Hanna, but Alice will always be grateful to them for how kind they were when Hanna finally returned to Cambridge.

She ushers them into the living room, where she has collected quite a few guests now (it is starting to feel like a large holding pen), and tries to emulate Kemi’s ease in pointing out the drinks, though she is conscious of sounding less like a suave host and more like an anxious waiter. As she goes through her drinks spiel she is remembering how these girls switched their student house when they heard Hanna was coming back, so that she could live with them instead of alone in halls; and now Alice finds she wants to offer them more than just rum or vodka or gin, though nothing will ever be enough.

She says, ‘And there’s milk pudding, too. Please do help yourselves.’

‘Sorry, what is it?’ Santiago says.

‘Milk pudding. It’s Brazilian. My flatmate Vitoria made it.’ She tries to remember what Vitoria has told her. ‘It’s called pudim de leite condensado.’

‘It looks very nice,’ Lavinia says. ‘I like your Portuguese accent.’

‘Vitoria made me practise.’

‘It’ll be full of calcium,’ Lola observes.

‘Yes,’ Alice says. She is on the cusp of listing more of the pudding’s merits when the doorbell goes again. ‘Excuse me,’ she says.

On the doorstep are a couple of young men in a smart-casual uniform of jeans and blue shirts. They introduce themselves as James Symonds and Ye Chen, Hanna’s friends from the Foreign Office, each proffering his surname automatically, as if at a networking event.

‘I’m Alice, Hanna’s twin,’ Alice says, since this seems like the most pertinent fact about her.

‘Really?’ the man called Ye says. ‘Hanna never mentioned a twin. You don’t look like her.’ He sounds both fascinated and suspicious, and Alice has to repress the urge to go and find a childhood photo as proof.

Ye is holding a bottle of wine, and James is holding a large plastic carry case with a metal grill at the front. Alice glimpses movement, a flash of fur and eyes gleaming in the darkness within.

‘Did you bring a cat?’ she asks, alarmed.

‘No, it’s a ferret,’ James says.

Alice considers various follow-up questions, but doesn’t quite know how to ask them.

They go down the hall, but James hesitates at the sitting-room door. ‘Is there somewhere quieter I can put him? He’ll go to sleep quite happily if it’s quiet.’

‘Yes, of course,’ Alice says, trying her best to be a good hostess. ‘You can put him in my bedroom.’

‘Thanks,’ he says, following her back across the hall.

‘Does he live in that box?’ Alice asks.

‘Oh no,’ James says. ‘He’s a house ferret. It’s just that I’ve been visiting my parents, and I didn’t want to put him on his lead on the Tube. And I don’t want anyone stepping on him once the party takes off.’

She is thirty-two; she shouldn’t still be living like a student. But this place was meant to be temporary, sourced quickly from SpareRoom one day when she realized she couldn’t possibly live with her mother a moment longer.”

Alice hopes the party does take off. She opens her bedroom door for James, and he places the carry case carefully down. Momentarily, Alice takes in the unwanted vision of her bedroom through James’s eyes: peeling paintwork, a small double bed that takes up most of the floor space, an IKEA chest of drawers wedged in the corner and a narrow built-in wardrobe, the door of which can’t open fully because the bed is in the way. She is thirty-two; she shouldn’t still be living like a student. But this place was meant to be temporary, sourced quickly from SpareRoom one day when she realized she couldn’t possibly live with her mother a moment longer. It was supposed to be a stepping stone to somewhere else, somewhere of her own. To furnish it properly would be an admission of defeat, and yet what is she other than defeated? In another decade, she will no doubt still be here, perhaps with different Brazilians, but still sleeping alone every night in this small, bleak room.

‘Nice place you’ve got here,’ James says, and Alice hopes, since he works in diplomacy, that he is capable of lying more convincingly than this.

James adds, ‘I’ll let him out at some point so he doesn’t get too claustrophobic, but only in here, with the door shut. Is that OK?’

‘Sure,’ Alice says, not feeling very sure.

‘He’s extremely well trained. And there’s not much in your room for him to chew on,’ James says.

‘No, I suppose not.’

‘It’s quite minimalist.’

Alice nods.

‘Not much in it at all, actually,’ James says.

Unwillingly, Alice surveys her room again.

‘Just the bed and the chest of drawers, really,’ James says.

They return to the sitting room, and amazingly there is Hanna herself, having arrived whilst Alice was dealing with the ferret.

‘Hi Alice,’ Hanna says when she sees her. And then she actually hugs her. Alice feels overcome by the bounty of Fortune as her sister’s arms go round her. Perhaps this is how it will be: she and Hanna will just pick up where they left off. (Although where they left off, it occurs to Alice now, was complicated enough even without a dramatic falling-out.)

‘Thanks for the party,’ Hanna says.

‘Well, Kemi did most of it.’

‘She said the same about you. What a modest pair you are.’

‘Welcome home,’ Alice says. She has decided she no longer wants to be one of those people who are always too afraid to say what they mean. So she adds, ‘I’m so glad you’re back.’

‘Me too, I suppose,’ Hanna says. ‘All things considered.’

‘Kemi says you’ve found somewhere to live.’

‘Yup. Move in next week. It’s in Kennington, a house-share with a couple of others. They seem OK. Can’t sleep on Kemi’s futon forever.’

‘If you need help moving, I’m free.’ She is always free.

Hanna smiles at her. ‘Thanks, Alice.’

And Alice has a brief, out-of-body sensation: here she is, chatting casually to her sister.

Then the doorbell goes again, and Hanna says, ‘Well, I’d better mingle,’ and the moment is over. But Alice looks forward to the other conversations they might have this evening.

She opens the door to find Michael and Olivia outside. Alice is more relieved to see them than she might have expected, even Olivia. Two more people she knows at this party.

‘Thanks so much for coming,’ she says as she takes their jackets and hangs them on the crowded rack.

It has been a long time since she has seen them together. The thought worries her, and is hard to shake once it has arrived. She reminds herself again that it is impossible to judge other people’s marriages from the outside.”

As ever, Michael looks rather ill at ease out of a suit. Tonight he is wearing a crisply ironed blue shirt and jeans that look like they might also have seen the iron. Olivia is strikingly pretty in a green dress and red lipstick. Alice realizes that it has been a long time since she has seen them together. The thought worries her, and is hard to shake once it has arrived. She reminds herself again that it is impossible to judge other people’s marriages from the outside. But it has been a surprisingly tumultuous relationship for Michael to be involved in, not at all the kind of thing they might have imagined for him. There was the original engagement straight after university, which was quickly broken off, and then the first wedding nine years ago, in Italy, that was cancelled at the last moment. By the time they got to the second wedding three years after that, in Islington Town Hall, the whole family was on edge in case this ceremony didn’t go ahead either, Hanna wondering aloud how many run-ups Michael and Olivia were going to take before they finally managed to complete a wedding. (Hanna hadn’t yet had a broken engagement of her own; later on, she might have been more sympathetic.) But then there was Olivia coming in, serene in her huge ivory gown, her waist tiny above the voluminous folds of the skirt, a bouquet of peonies in her hands. In his speech at the reception, Michael described himself as the luckiest man alive. Alice thought he looked exhausted.

‘We can’t stay long,’ Michael tells her now. ‘I have a lot of work to do tomorrow.’

‘On a Sunday?’ Alice says before she can help herself.

‘I’m in the middle of drafting a very important memo.’

‘Parties aren’t really Michael’s scene these days,’ Olivia says. ‘Too much fun. Not enough tax.’

Alice sees Michael’s jaw tense, though he doesn’t say anything.

‘They’re not really my scene either,’ she says. ‘I was so nervous earlier that I felt a bit sick.’

‘It does seem like an unnecessary carry-on,’ Michael says.

‘Why go to all this effort, Alice? I don’t think she’ll really appreciate it.’

‘She will,’ Alice says. ‘She does.’

‘Nobody ever throws parties for me,’ Olivia says, with a pointed look at Michael as the three of them move down the hall.

‘I held that dinner party for your birthday last year,’ Michael says.

‘Oh yes! Talking politics over our cappuccinos. It was all very wild.’

‘Is Hanna here yet?’ Michael says as they enter the living room.

‘Yes, she’s over there in the corner with Kemi.’

Michael nods. ‘I need to have a chat with her.’

‘About what?’

‘Making sensible choices. Investing in property, not throwing all her money away in rent. Hopefully she’ll be more receptive this time.’

He disappears, leaving Alice and Olivia alone.

‘He used to have chats with me about investing in property,’ Alice says sadly. ‘I think he’s decided I’m a lost cause now.’

‘Owning property is very unimaginative,’ Olivia says. ‘It ties you down. I miss my freedom desperately.’

Alice doesn’t think she’d miss her freedom too much if she owned a half-a-million-pound flat in Kentish Town, but she says, ‘I suppose renting gives you a bit more flexibility. But security is nice too.’

‘Most of the ills of our society can be traced to ownership of one kind or another,’ Olivia says.

Alice reminds herself, in a ritual she often seems to carry out in Olivia’s presence, that Olivia has a good heart (and if Alice hasn’t seen much evidence of this, then perhaps that is because she hasn’t been looking hard enough). To pre-empt any more of Olivia’s well-rehearsed views on the oppression of ownership, she says, ‘Can I get you a drink?’

‘I can’t drink at the moment,’ Olivia says. She gives Alice a meaningful look.

‘Oh right,’ Alice says. ‘Oh dear. Are you feeling unwell?’

Olivia puts her hand to her stomach, still looking at Alice meaningfully.

‘Do you have a stomach upset?’ Alice says.

‘No,’ Olivia says, sounding irritable now. ‘I’m pregnant.’

‘Oh!’ Alice says. ‘Oh.’ Reflexively she thinks, Now he won’t ever be free of her. Then she is shocked at herself.

‘That’s wonderful,’ she says to Olivia. ‘Wonderful! Wow!’ I’m going to be an aunt, she tells herself, not quite believing it.

‘Don’t tell Michael I told you,’ Olivia says. ‘He doesn’t want to tell his family yet.’

His family. Alice isn’t sure if she is imagining the distancing quality of the pronoun. She says, ‘Of course, I understand. That makes sense. This is wonderful news! Let me get you a soft drink. Lemonade? Coke?’

Olivia reacts as if Alice has just offered her a puff on a crack pipe. ‘Do you have anything less sugary? A lime and soda, perhaps?’

‘I’m afraid we don’t have any limes,’ Alice says. ‘Or soda.’

‘Sparkling water?’

‘No, sorry,’ Alice says humbly.

‘Just tap water then,’ Olivia says. ‘Do you have any little canapés that I can nibble on? It tends to help with the nausea. There’s not much I can eat at the moment, but I can usually tolerate a bit of flaky pastry or a few olives.’

‘I think there are some sausage rolls in the kitchen,’ Alice says. She is ready to acknowledge her failure as an adult. Plenty of lemonade and party rings to go around, but no sparkling water or vol-au-vents.

‘I’m a vegetarian,’ Olivia says. Her tone is reproachful, though Alice is almost certain this is new information.

She says, ‘Oh! Sorry. Well… I could, sort of, disembowel it for you? Take the sausage bit out and leave you with the pastry?’

‘Disembowel it?’ Olivia says.

‘Or!’ Alice says in relief, as she remembers. ‘There are some breadsticks somewhere. I’m sure there are.’

‘Fine,’ Olivia says magnanimously.

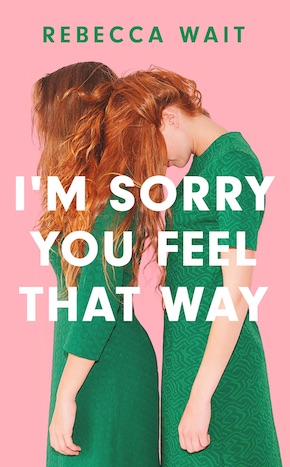

from I’m Sorry You Feel That Way (riverrun, £16.99)

Rebecca Wait has written for the New Statesman, Independent and Pool on subjects as diverse as suicide, cults and autism and appeared on Woman’s Hour. Her third novel Our Fathers, published by riverrun in 2019, was a Guardian book of the year and a thriller of the month for Waterstones. She lives on the outskirts of London. I’m Sorry You Feel That Way is published by riverrun in hardback, eBook and audio download.

Rebecca Wait has written for the New Statesman, Independent and Pool on subjects as diverse as suicide, cults and autism and appeared on Woman’s Hour. Her third novel Our Fathers, published by riverrun in 2019, was a Guardian book of the year and a thriller of the month for Waterstones. She lives on the outskirts of London. I’m Sorry You Feel That Way is published by riverrun in hardback, eBook and audio download.

Read more

@QuercusBooks

Instagram: quercusbooks