A shower of stardust

by Antoine Laurain

It was long after nightfall, and a soft breeze played over Guillaume’s face. He had positioned his telescope to the portside and aft, to observe the constellations of Centaurus, Circinus, Volans and the Southern Cross. With a yellow glass disc placed over the end of the telescope, the image was more sharply focused. He was comfortably installed in a blue velvet-upholstered cabin chair that he had brought on deck for the occasion, together with a rosewood side table and a crystal ink pot. With his goose-quill pen, he noted down measurements that appeared to correspond to his calculated estimates. The wrought-iron lantern hanging beside him swung gently, with a low creaking sound, then puffed out. Immediately, the ship’s boy crossed to the where the astronomer was sitting, to relight it.

‘Leave it, my young friend,’ Guillaume told him. ‘I’ve completed my observations for tonight.’

He shook a little blotting powder over the page to dry the ink, then blew on the paper and closed his notebook full of diagrams, sketches, figures and dates.

The ship seemed to float in the very darkness itself, the ocean indistinguishable from the sky. From time to time, the silhouette of a member of the crew passed by, lit by the flaming torches on the poop deck. A mixture of pitch and resin burned in great, octagonal glassed cages, like lanterns placed there by some giant Cyclops. The mariners seldom spoke to him – not that they felt any hostility towards his person, they simply had no desire to disturb him. His status as the ship’s astronomer, and his royal mission, set him apart from the rest of the company. It had taken Guillaume a while to understand that the captain’s men, even the highest-ranked officers, could not permit themselves to distract him from his thoughts, his observations, and his note-taking. They would draw near, but stand a few paces off, waiting for the scientist to take notice of their presence and turn towards them, before greeting him and addressing a few words. They hardly dared cough to catch his attention. Guillaume told them often that they must not stand on ceremony, but the men of the Berryer refused to break the golden rule: never interrupt the astronomer at work.

Guillaume took a few paces around the deck to stretch his legs, then gripped the ship’s rail and tried to make out the horizon with his naked eye. He saw nothing but darkness. He looked up into the night sky. The vault of heaven was covered with stars, and the night was so clear that he could see numerous constellations. He knew the strange, black star-charts intimately. Each point of light bore a name. Suddenly, a bright streak shone pale mauve across an empty stretch of sky, and Guillaume stepped back in astonishment. More, infinitesimal gleams of light appeared. They glittered and sparkled as a burning wind set the torch flames flickering wildly. The sky glowed purple, in the dead of night, and the men of the ship hurried to starboard. Some muttered quietly among themselves, and the entire bridge seemed gripped with fear.

‘Iron rain!’ The lookout’s voice rang from the top of the mainmast. The men exchanged glances and some of the crew crossed themselves. A glowing and yet sunless dawn was just breaking across the sea. A metal particle no bigger than a small slug bounced off the deck at Guillaume’s feet. He bent to grasp it between his fingers. Twisted and still scorching hot, the tiny scrap of metal had crossed the universe to ricochet off the boards beneath his feet.

What you are picking up off the deck is stardust! These specks have taken millions of years to land at your feet. Keep them safe, give them as a gift to your wives and your sweethearts!”

‘Meteors,’ said Guillaume softly. ‘A meteor shower,’ he corrected himself. He had read accounts of the phenomenon, which occurs when an asteroid falls through Earth’s atmosphere, but he had never seen it other than in engravings. Sometimes the block of extraterrestrial ore fell to earth, or into the sea, in one piece. Unschooled, superstitious men called these ‘thunderstones’, because their fall through the atmosphere caused a break in the clouds and a reaction that produces a sound like thunder. Ancient druids and other wise men thought that the stones, which were far bigger than an ordinary piece of rock, were divine thunderbolts sent to Earth to warn mankind to mend its ways, or risk worse punishment in future. Alternatively, the mass would break up into tiny particles, creating ‘Perseids’, otherwise known as ‘shooting stars’ or ‘iron rain’. A meteor shower. Such was this. The small fragments were falling continuously onto the deck now, while the sky filled with pale, purplish streaks not unlike the aurora borealis. Vauquois came and stood beside Guillaume.

‘My men dislike this phenomenon. They say it brings bad luck. You are a man of science, Guillaume. Would you care to explain to them what is happening, in reality?’

Guillaume nodded.

‘I am ever at your service, Captain Vauquois.’

‘Gentlemen!’ the captain called out. ‘Our esteemed guest, a man who knows all there is to know about the stars and the planets, shall tell us the origins of the iron rain – lend him your ears!’

Guillaume did his best to explain to the company that the stars were like planets. They should imagine a small star falling like a vase toppling off a table and shattering on the floor.

‘What you are picking up off the deck is stardust! These specks have taken millions of years to land at your feet. Keep them safe, give them as a gift to your wives and your sweethearts!’ Guillaume was warming to his subject. ‘They are the beating heart of the universe. See the sky and all its colours!’ He swept the air with his arm. ‘Behold, my friends, the work of God and the beauty of our world!’

The men listened, silent as a church congregation, nodding their heads. Captain Vauquois applauded his astronomer solemnly, and his men followed suit. Guillaume bowed his head in friendly acknowledgement. He turned and stood behind his telescope, while some of the men bent to pick up the scraps of metal that continued to fall with a soft tinkling sound. One struck the telescope’s tube, producing a tiny spark and ricocheting off onto the deck. Guillaume started in surprise, then bent over his instrument: two small nicks in the brass formed a semicolon. He peered around, hunting for the miniscule meteor, then spotted it at last, caught between the ship’s boards. He fished it out and slipped it into his waistcoat pocket. He would give it to Hortense.

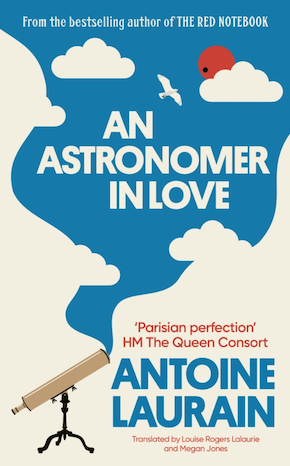

from An Astronomer in Love (Gallic Books, £16.99)

—

Antoine Laurain is a French novelist who previously worked as screenwriter and an antique dealer. His novel The President’s Hat was awarded it the Prix Landerneau Découvertes and adapted for television in France. The English translation was a Waterstones Book Club and ABA Indies Introduce pick, and a Kindle Top 5 bestseller. His novels have been translated into over twenty languages, and The Red Notebook (2015), one of Gallic Books’ all-time bestsellers, was selected for HRH the Duchess of Cornwall’s Reading Room. His other novels are French Rhapsody (2016), The Portrait (2017), Smoking Kills (2018), Vintage 1954 (2019) and The Readers’ Room (2020). An Astronomer in Love is published by Gallic Books in hardback and eBook, translated by Louise Rogers Lalaurie and Megan Jones.

Read more

antoinelaurain.blogspot.com

@BelgraviaB

Author portrait © Pascal Ito/Flammarion

Louise Rogers Lalaurie is a British translator and writer based between France and the UK. Her literary translations from French include thirteen novels, several short stories and over thirty non-fiction titles.

louiserogers.blog

@LLalaurie

Megan Jones is a publishing assistant at Gallic Books and a freelance linguist.

Linked In: Megan Jones