Into the darkest corners of the dark ages

by Rebecca Stott

London, one of the greatest and oldest cities in Europe, is now nearly two thousand years old. Most people know that it began as a small Roman trading post on the north bank of the Thames around 43 AD, but few people know that, after the Romans abandoned Britain in around 410 AD, it lay empty for almost four hundred years.

When I first read about the mile-wide ruined city, it seemed to me like Sleeping Beauty’s castle in the fairy tale, creepers and brambles closing over the great Roman walls and ornate stone buildings and statues, wolves scavenging, crows and red kites nesting, trees pushing through the roofs of crumbling palaces, the amphitheatre and warehouses along the banks of the Thames open to anyone who wanted to walk there.

But for four hundred years, archaeologists believe, virtually no one walked there. They knew this because the number of objects that they have found inside the city walls that can be safely dated to the period 450 to 800 AD – belt buckles or brooches or swords dropped by local people – during the years of the city’s ruined and crumbling centuries, can be fitted into a single shoebox.

Once I had decided to set my novel in the ruined city in 500 AD, around eighty years after the Romans left, I began to read every book and article I could get my hands on. I wanted to see the ruins for myself in my mind’s eye, smell it, explore it for myself, push open doors into overgrown gardens and courtyards. I was following my curiosity. That’s what you have to do as a fiction writer sometimes: trust your curiosity. And my curiosity was quickly turning into an obsession.

In the early stages of my research an archaeologist warned me that I was heading into the one of the darkest corners of the dark ages, one of the most unknown periods of British history. When I asked him how he thought it might have looked after eighty years or so, he showed me photographs of the modern city of Pripyat, cordoned off after the explosion of Chenobyl just over thirty years ago. It was already overgrown, cats raising their young in the rusting drawers of old filing cabinets in schoolrooms with no roofs.

Waves of migrants were coming into Britain. They needed to co-operate with each other, learn from each other, and that surely meant they had to learn each other’s languages and share their skills.”

In order to build my world I spent five years reading about and researching sixth-century sword-making and smithing, farming practices, clothing, native and migrant languages, patterns of migration as well as religious beliefs and gods. I travelled around the country to interview archaeologists and historians. I spent a day in a forge with a smith who used Anglo-Saxon methods of sword-making. Everywhere I asked questions. Why did no one go inside the ruins? What was daily life like out there? Might people have thought that smiths had special powers? How did people live alongside others who worshipped different gods?

Gradually, glimpses of daily life in the sixth century came into view. Waves of migrants were coming into Britain from the northern parts of Europe, people we now call Saxons and Jutes and Angles, driven from their own lands by crop failures and rising sea levels. We know that the incomers were farming alongside the native Britons. Everyone must have been trying their best to feed their children, get through the winters, learning to make pots and ironwork again after centuries in which the Romans had imported so many high-end goods. They needed to co-operate with each other, learn from each other, and that surely meant they had to learn each other’s languages and share their skills. They would have had little time however to go exploring inside the walls of a great stone, crumbling city full of strange gods and statues.

One particular tiny object gave me the most tantalising glimpse into this period, and brought the two sisters of my novel into view. It was a brooch only a couple of inches wide found in the ruins of an excavated Roman bathhouse and villa on the north bank of the Thames in 1968. It has come to be known as the Billingsgate brooch. The archaeologist who found it knew as soon as he cradled it in his hands that it was unique. He could tell from the pattern that it belonged to a Saxon woman who had found her way into the ruined city. The brooch would have been one of a pair designed to nestle against her collarbone and hold her tunic in place. If she had dropped it on top of the fallen roof tiles of this small private bathhouse, what was she doing in there? Was she on the run? Was it a love tryst? Was she alone or with others?

Historians and archaeologists know nothing about what the Billingsgate brooch’s Anglo-Saxon owner might have been doing in the ruined city or how she got there or what she might have been looking for – or hiding from. She is lost to history. But fiction can sometimes take steps into the unknown where historians cannot reach. With this rusted talisman in my hands, I set out to imagine her story.

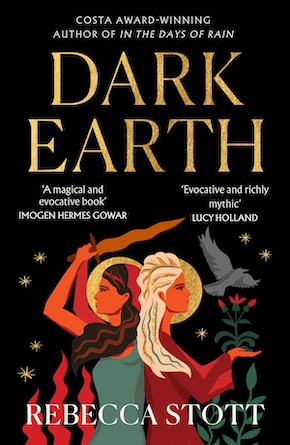

My novel Dark Earth tells the story of Anglo-Saxon sisters Isla and Blue. They are second-generation migrants, the daughters of a great migrant smith who forges fire-tongued swords, swords that have an extraordinary pattern running down their centre, the result of a secret and highly skilled method he has brought with him from northern Europe. His skills have attracted the attention of a local warlord who knows that he can use the fabulous swords to make alliances with other warlords. He has exiled the smith and his daughters to a mud island in the Thames so he can make sure the smith makes the swords only for him. What he doesn’t know is that Isla, the smith’s eldest daughter, has been working alongside him secretly, learning his skills. Trouble is, women are not allowed to enter the forge or touch the blades, so Isla must keep her skills hidden.

When the great smith dies, the sisters are forced to go on the run. In the ruined city of Londinium, they find sanctuary in a secret underworld community of squatters, migrants, travellers and looters, led by the mysterious Crowther. When the warlord and his men track the sisters down and enter the city, the women, with the help of Isla and Blue, have to find their own kind of power through myth and magic and storytelling.

Most historical novels set in this period of British history are dominated by stories of men on horses with swords, tribes massacring each other. Women tend to feature only as trophies or as sisters or wives or maids. But now that historians have started to look more closely at the history of women, and filmmakers are hungry for new angles and vantage points too, new stories are coming to light or being retold with women at their centre, not just Boudicca and Guinevere, but ordinary women like my second-generation migrant sisters, living in a multicultural Britain of different languages and gods, who have to work together with other women to survive against the odds.

—

Rebecca Stott is a novelist, broadcaster, historian and Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature. She is Professor Emeritus at UEA. Her previous books include Darwin’s Ghosts and Darwin and the Barnacle, the novels Ghostwalk (a New York Times bestseller) and The Coral Thief, and the Costa Award-winning memoir In the Days of Rain, an account of her childhood growing up in a Christian fundamentalist cult called the Exclusive Brethren. She lives in Lewes. Dark Earth is out now in paperback, eBook and audio download from Fourth Estate.

Read more

rebeccastott.co.uk

@RebeccaStott64

@4thEstateBooks