A time for reading

by Stéphane Carlier

It is the middle of the afternoon on a Sunday in March. She has just woken up from a nap. The snow is no longer falling but its brightness is still being projected onto the ceiling of their apartment. It is rather lovely. The cat is watching her from a pouffe opposite the sofa with a look that says, Who are you and what are you doing in my house? before opening his mouth in an enormous yawn. JB has been helping a friend move house since the morning, and lunch at her parents’ has been cancelled.

She takes advantage of how quiet the apartment is and has a bath, then she calls her mother. Afterwards, she gets a chicken and mushroom pie out of the freezer for dinner and makes herself a cup of tea. While the water is boiling, she receives a message from JB (We’re going back to Sevrey, we won’t be done until the evening) and she sends back two emojis (flexed biceps and a kiss). She opens Instagram, closes it again very quickly, puts her phone down on the counter and looks out of the window, thinking that she could quite happily make love in this moment. The snow, the cold and the soft silence probably have something to do with it. She could happily make love to Jacob Elordi. She discovered him for the first time this week in a series she was watching with JB. Every time he appeared on screen, she wondered if she was managing to hide her attraction to him. She has always liked tall, slim, borderline skinny men. Like the customer who came into the salon a little while ago. She hasn’t forgotten his long hands and slender fingers, imagining them clasped around her waist. She also remembers his mouth, picturing it slightly open, breathing warm air, just a few centimetres from her own. She doesn’t know why this image has such an effect on her…

He left a book at the salon. A paperback. What was it again?

…

Nothing at first. Nada, niente, nichts. There’s that first sentence, as famous as an advertising slogan or the chorus of a song from childhood, and then it all gets complicated. The words are like lines of ants before her eyes. It’s about François I, Charles V and metempsychosis. François I is a king of France. Charles V’s story is already more complex. And it’s not like she’d have heard of metempsychosis at the salon or from JB. What is this book?

She has a sip of tea, pulls the tartan blanket back over her legs and carries on reading. One sentence stands out to her like somebody waving. I would lay my cheeks gently against the comfortable cheeks of my pillow, as plump and blooming as the cheeks of babyhood. She is moved by this image, and even more moved by what follows. It is about a moment of mistaken joy. A man wakes up in bed. He is in pain and is glad to see light underneath the door. It is morning and he can ask for help. But no: the ray of light comes from a gas lamp that has just been extinguished in the corridor. It is still nighttime; he has only been asleep for a few minutes and will have to endure several more hours yet…

She carries on reading, wanting to know more – she is curious and always has been. Another sentence stops her in her tracks: When a man is asleep, he has in a circle round him the chain of the hours, the sequence of the years, the order of the heavenly host. Impenetrable. She frowns but continues, no longer quite so moved. The words become lines of ants once more. Proust is talking about the position of his body in the bed, about his stiff arm and the furniture situated around him. So many words, simply to say that he can’t sleep – the guy obviously has a problem; he should get some help.

It suddenly makes sense. It’s about a man in bed, drifting between sleep and wakefulness, dream and reality, past and present. His state of confusion is familiar to her. She too has experienced it.”

She closes the book and chucks it onto the sofa. That will do, thank you. There are plenty of people who like reading that kind of thing; she prefers Jacob Elordi. She turns to face the window, thinking about the actor’s eyes and his sad cocker-spaniel expression, and then, strangely, as if something had just clicked in her brain, she remembers the last sentence she read. She picks the book up again and finds the page and sentence she is thinking of: everything would be moving round me through the darkness: things, places, years. And it suddenly makes sense. It’s about a man in bed, drifting between sleep and wakefulness, dream and reality, past and present. His state of confusion is familiar to her. She too has experienced it when falling asleep or just after waking up, no longer sure if she’s in her apartment, the house where she grew up or her grandmother’s house in Besançon.

She sits up, concentrates. Proust hints that he’s reaching the end of the back-and-forthing. At least, the character in his book does. At the close of one chapter, he says he is going to reflect on his life of old. To return to the past for good, and, just like Alice falling down the hole that took her to Wonderland, never come back. In Search of Lost Time. Why not go on the journey? She has always been interested in the past. The veils, the long dresses and the horse-drawn carriages dashing along cobbled roads. There used to be a print above the sofa in the living room of her nanny’s house, of a painting which was probably from the same era as the book. It showed a woman standing in the wind. She had a long white skirt and was holding a green parasol to protect her from the sun. Clara had looked at it so intently that the woman appeared to be moving, and sometimes even turning around to silently watch her, her eyes narrowed in the blur of the distance. It’s funny, it’s been years since she’s thought about it. And reading has brought this memory to mind, as if it had been hidden behind a folding screen that Proust has just moved with great delicacy.

She has only read about twelve pages, but she already knows how their relationship is going to play out. She will have to work hard and persevere with him, often through fog, sometimes in darkness, not be put off by his use of nested sentences and the imperfect subjective, exercising patience and a dictionary when necessary. And he, upon regular intervals, will blow her away just when she is least expecting it.

The more she reads, the better she understands him. He doesn’t use complicated words – it’s just that his sentences often wander elsewhere. Once she realises this, once she understands that he isn’t abandoning her and will come back to find her, it all gets much easier. In fact, his sensitivity is what makes him so unique. People aren’t used to feeling things so intensely in day-to-day life. And adapting to that level of subtlety is what requires effort on the part of the reader. That is what demands your full attention – and means you can’t read Swann’s Way with Rage Against the Machine playing in the background. Well, that’s just an example.

Plus, why not admit it? She is rather proud: she is reading In Search of Lost Time. She can do it, and that is quite something.

Anaïs wouldn’t be able to read In Search of Lost Time; Nolwenn doesn’t even bear thinking about. And the fact that it started the way it did, by chance and out of sheer curiosity, adds to her growing sense of triumph.

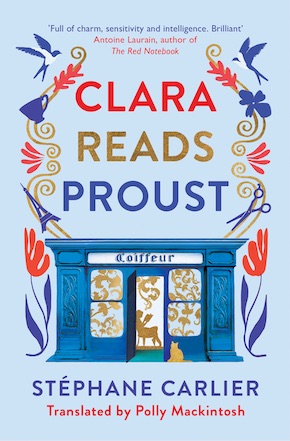

from Clara Reads Proust, translated by Polly Mackintosh (Gallic Books, £9.99)

—

Stéphane Carlier grew up around Paris in the 1970s. He worked for the French Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs for several years, with whom he spent a decade in the United States. He has also lived in India and Portugal. Clara Reads Proust is his eighth novel and the first to be translated into English.

Read more

@GallicBooks

Author photo by Claire Deweggis

Polly Mackintosh is an editor and a translator from French. She has translated the work of Alain Ducasse, Antoine Laurain and early French feminist Marie-Louise Gagneur, amongst others. She lives in London.

@pollymack95