Towards an aesthetics of (im)perfection

by Mika Provata-Carlone

“Austenites will appreciate the historical context Johnston provides… Students and devotees of Austen will appreciate the light shed on a lesser-known part of her career.” Publishers Weekly

There is a certain aura of myth and legend when it comes to Jane Austen. We think we know so much about her, and at the same time we apparently never tire of being thrilled by the mystery that seems to surround her, from her private life to what is quite simply her writerly genius. Yet if we pause and think, her art is a supreme celebration and triumph of litotes at every level: we know a surfeit of biographical details, thanks to her surviving correspondence and the copious industry of her family who set out to ensure her posthumous persona but, arguably, little of the individual person; we feel as readers that her literary corpus is as vast and plethoric as her indelible mark on the cultural tradition and the popular imagination, yet her six published novels, on which this extraordinary Nachleben and timeless presence rest, were written during the course of six years and ten months.

It is a tension of proportions and of a certain minimalist magnitude that has mystified critics and biographers. We cannot resist, it seems, the effort of near-forensic analysis of the genealogy of her work: just how did she do it? Typically, her writings are taxinomised in strict Darwinian fashion, from low amorphous creatures, to infantile lives, to perfectly evolved species. In fact, Austen and her writings can be said to be the quintessential victims of both pride (that of her nephew and earliest biographer, James Edward Austen-Leigh) and prejudice – that of nearly almost every generation of Austen anatomists and scholars, who observe this linear progression of worth (or worthlessness) with almost religious fervour.

In Jane Austen, Early and Late Freya Johnston seeks to show the dynamic continuity of a life and mind, the creative praxis as a whole, in all its stages of metamorphosis and recalibration. Above all, she sets out to reveal Austen as a thinker, as a reflective auctor and actor, resisting the equally tenacious tradition that sees Austen as a composer of divertissements, of cloud-cuckoo-lands of privilege and affectation. Johnston’s Austen thinks hard, feels deep, sees with penetrating clarity, and writes with words that capture infinitely more than their contextual circumstances. More than two hundred years on, Austen remains as contemporary and as audacious, as keenly conscious of public pulses and private impulses as ever. Johnston’s book, a scholarly study written with irresistible directness, is a sprightlily intelligent, deeply engaging reappraisal of a highly introspective and brilliant female voice and mind, of a daring public commentator and artist.

Johnston has a rare talent for interweaving the critical tradition concerning Austen and the full gamut of textual theory and cultural hermeneutics with effortless fluency and naturalness.”

The retrospective thrust is in fact a declaration of intent, of a cognitive but also socio-politically alert ethics of academic practice and intellectual resolve. Johnston’s theoretical referent is Quentin Skinner’s rather underappreciated concept of the “mythology of prolepsis”, from his ‘Meaning and Understanding in the History of Ideas’, a 1969 essay that we should perhaps do well to bear keenly in mind especially today: “it is rather easy, in considering what significance the argument of some classic text might be said to have for us, to describe the work and its alleged significance in such a way that no place is left for the analysis of what the author himself meant to say, although the commentator may still believe himself to be engaged on such an analysis. The characteristic result of this confusion is a type of discussion which might be labelled the mythology of prolepsis.”

Johnston has a rare talent for interweaving the critical tradition concerning Austen and the full gamut of textual theory and cultural hermeneutics with effortless fluency and naturalness. She sets the ground for a discussion that is as meaningful as it is beguiling and graceful. She dismisses the evolutionary, geneticist account of Austen’s authorial development as an advancement from primitive or protozoic attempts to perfect organisms. As she has said elsewhere, the earlier writings show Austen “thinking or rehearsing for the role of an author”, echoing Virginia Woolf’s own comment that they show “Jane Austen practising”. What is emphasised is the consciousness of agency, the determined deliberation and the development of both skill and mind. There is experimentation, improvisation, heuristic play and serious self-examination, the cultivation and exploration of a radical imagination. Johnston’s conclusion could not be further removed from the Barthean pronouncement of “The Death of the Author”: “people and their stories”, authors and their writings, “do not end. They grow.”

The 27 surviving early texts that Austen composed between the ages of roughly 11 and 17 are far from spontaneous productions. They have been meticulously transcribed, and as carefully preserved. Johnston argues that Austen revisited these ‘Juvenilia’, as they came to be called, throughout her writing life, reflected on them, not only in terms of plot or storylines, but especially as the vivid micro-universes of the worlds she wished to give life to in her published novels. They were repositories of memory, of the first experiencing of things, of original insights, and even of the social art of banalisation. Far from being “childish effusions”, as they were once described, they were the Ur-texts on which Austen’s own civilisation of words, characters and lives depended.

Increasingly, Austen’s novels are deemed to be in need of adaptation, familiarisation, modification and modernisation, a process that can rely heavily on exploiting with blaring sonority the intimate satirical theatrics and family performances that gave a young Austen her sense of voice, drama and audience. The weight is placed unyieldingly on the farcical, the caricatural event, on the self-ironic and the social burlesque. This, as Johnston shows, is to miss (or to deliberately erase) Austen as a commentator, as a female agent, as a shrewd yet empathetic analyst of human nature, fate or situation. It is to suppress, intentionally and even violently, what G.K. Chesterton saw (as Johnston reminds us) as the “very real psychological interest, almost amounting to a psychological mystery, [which] attaches to any early work of Jane Austen.”

Austen insists on the prioritising of intended meaning over pat fictionalisation, on the dramatic articulation of a question (of many questions) over mere plausibility.”

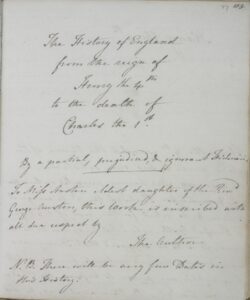

Title page of Jane Austen’s The History of England, 1791. Wikimedia Commons. Browse the complete manuscript at the British Library

Johnston explores and redefines the apparent duality between Austen the private individual and Austen the published author and memorialised persona – a duality poignantly captured in E.M. Forster’s cryptic formula ‘Miss Austen and Jane Austen’ (TLS, 1923). For Johnston, the relationship is more yin and yang than tug of war, with the two being dimensions of the whole rather than markers of centrifugality and of disruption. They inform the remarkable precision of Austen’s narrative technique, her mastery of both craft and inspiration, her talent (and instinct) for open-endedness, even her often overlooked radicalism, evinced in her conscious resistance against the expected conventions of her time. Austen insists on the prioritising of intended meaning over pat fictionalisation, on the dramatic articulation of a question (of many questions) over mere plausibility. “In her published novels, the resistance to finality… becomes a moral problem or question as well as a joke about the limits of novelistic ‘pictures of perfection’”, as she termed them in an 1817 letter.

Her earlier writings would inspire a vehement anti-tradition to her formal published corpus: they were proclaimed burnable and thus damnable, but they were also fiercely acknowledged as too intimate a part of what would progressively emerge as the Austen Monument to be easily destroyed. They were shame-worthy sacred nothings, yet sacred nonetheless. Johnston writes against this depersonalised monument with engrossing insight, offering a vision of the extraordinary sensitivity and art with which Austen was so gifted. She places one of Austen’s phrases about families and buildings at the heart of her enquiry, an extraordinary formulation that encapsulates any gesture or process of being and civilisation. Rather than juvenilia, or the curios of a life, the early writings are integral parts of her nous, continually “preserved in a state of alteration”. It is almost a philosophical maxim to live by…

Borrowing from Wordsworth, and with that same strong sense of both progress and tradition, of change and continuity, Johnston will argue for a “deliberate preservation of affinities between all stages of the life of a woman” in Austen’s case, but implicitly also for the same critical process of development as regards our culture and humanity. She posits analysis, reassessment, re-evaluation but also recognition of a legacy, of an effort and of a journey, against theories and ideologies of denial, erasure or destruction. In this, she could be said to be aligning herself with Clifford Geertz’ famous injunction: “The essential vocation of interpretative anthropology is… to make available to us answers that others… have given, and thus to include them in the consultable record of what man has said” – and in the spirit and true sense in which these answers were originally formulated.

One can read Johnston’s study as an analysis of how to look at Jane Austen, but also, and very crucially, as an exploration of and a reflection upon the ways in which we should engage with the past, whether as a state of lost idylls, or as a more nebulous realm of unsatisfactoriness, darkness, guilt, ignorance or innocence. Her literary categories and classifications for “authorial growth” are equally resonant and lucid prisms for social analysis, historical contextualisation, the creation of coherent and polyphonic narratives, as opposed to dominant ideologies and theorising dogmas. She gives us Austen’s Zeitgeist not only in the well-rehearsed form of social structures, mores and conventions, but most importantly and excitingly in terms of an ebullient intellectual milieu, a state of historical unrest and of radical redefinitions as regards sensitivities and sensibilities, perceptions of and expectations from the self and its community, the angst and thrill of starting the New, without leaving anything of what has mattered behind.

One can read Johnston’s study as an analysis of how to look at Jane Austen, but also, and very crucially, as an exploration of and a reflection upon the ways in which we should engage with the past.”

Austen emerges as a fellow traveller of Goethe and Keats, taking on Byron and the Romantics, a challenge to the Brontës rather than their shabbier distant cousin. Johnston tackles the question of Austen’s education (in Rousseau’s sense as well as in the context of the sociopolitical agency of girls and women at the time), giving us an extraordinary portrait of an insatiably curious mind, a ceaselessly engaged sensibility. Austen was an avid reader, as much so, perhaps, as Virginia Woolf, and as sharply self-observant of herself in the act of reading and writing. Her conscious uniqueness versus her contemporaries comes not only from her choice of formal stylistics (crisp, tightly woven narratives, in opposition to the multi-volume, trendier doorstoppers), but also from her remarkable intertextuality, the complex, intentional semantics developed by Austen as a critical discourse, as a language of social analysis and of human experience, and as a way of being in her time, but also singularly ahead of it. Wordsworth, Keats, Mary Wollstonecraft, Samuel Richardson and Henry Fielding, Alexander Pope, Oliver Goldsmith, William Robertson and even David Hume (though not Edward Gibbon) are fellow wayfarers and interlocutors, in what Johnston shows to be a riveting, but also heated meta-fictional conversation. Austen’s constant and complex problematisation as regards History (capitalised) and the infinite interweaving (or tangled) threads that make up its human fabric is at the core of Johnston’s focus, and her reading of the embedded “discussions on history as a subject”, as the “vestigial idea of studying history as a ‘means of improvement’”, as Austen quips in Sense and Sensibility, reveals (or recovers) the latter’s heightened political sense and social sensibility, her intense engagement with her time, and with the people (grand figures or ‘mere’ individuals), who determined its course. History for Austen was both a part of the formative process of social identity and, when stultified, yet another societal mannerism to be abstracted and critically assessed, and daringly or comically analysed.

Such an approach brings Johnston in direct confrontation with Edward Said’s famous ‘post-colonialist’ (mis)construction of Mansfield Park in Culture and Imperialism, and she (refreshingly) takes no prisoners in accepting the challenge. In her own analysis she exposes Said’s deliberate “subject[ion] of the novel to a form of Whiggish misreading”: “the critical and political manoeuvres involved in [Said’s] writings are more evasive and less defensible than the teenage Austen’s bold, overt moves” in her mock History of England. Against such “critical and political manoeuvres”, Johnston finds Henry Fielding’s Modern Glossary, an anti-lexicon or expository analysis of words and the social function of their meaning, as a more pertinent key to Austen’s inspired and multivalent piffle and equally trenchant use of language. This allows her to bring to close focus Austen’s mordant suspicion of ‘universals’, of grand categories and blanket definitions, of sweeping generalisations and totalising abstractions.

“Like [Edmund] Burke, Austen endorsed both the communal view of things and the moral reality of exceptions to that view”; like John Grosse, her worldview was centred around the crucial assumption that “seldom, very seldom, does complete truth belong to any human disclosure; seldom can it happen that something is not a little disguised, or a little mistaken.” Austen, Johnston shows, “began from a very young age to think about the motives and scope of universal truths”, which allowed her an extraordinary creative freedom, free writerly will and freedom of spirit and thought, and also required of her an equally formidable commitment to self-examination, to sincere questioning, as well as affirmation. Rather than easy satire, her manner of thinking is a precise course of analytical reflection, of facts and opinions, principles and stereotypes, reality and publicly held views. For Johnston, this process is initiated, experimented on, systematised and developed in the early writings, to be perfected into an art that is Austen’s very own mark of an identity continually “preserved in a state of alteration”. It would lead, in the most essential manner, to the palpable achievement of the published adult novels. Johnston is clearly fascinated by Austen’s voice, mind, life, the heartbeat of her human and intellectual presence, and in Jane Austen, Early and Late she certainly lures us to share her enchantment and admiration. It is a beautifully written, meticulously argued study of an extraordinary public and private life, one that takes its readers seriously by engaging with them deeply – and with thrilling expectations of responsiveness and understanding. A rare example of scholarship, a deeply resonant, most welcome addition to our human conversation about what constitutes intelligence, tradition, legacy, humanity, the expression of a life, of being, time and experience.

Freya Johnston is University Lecturer and Tutorial Fellow in English at St Anne’s College, University of Oxford. She is the co-editor of Jane Austen’s Teenage Writings and the author of Samuel Johnson and the Art of Sinking, 1709–1791. Jane Austen, Early and Late is published by Princeton University Press in hardback and eBook.

Freya Johnston is University Lecturer and Tutorial Fellow in English at St Anne’s College, University of Oxford. She is the co-editor of Jane Austen’s Teenage Writings and the author of Samuel Johnson and the Art of Sinking, 1709–1791. Jane Austen, Early and Late is published by Princeton University Press in hardback and eBook.

Read more

english.ox.ac.uk

@PrincetonUPress

Mika Provata-Carlone is an independent scholar, translator, editor and illustrator, and a contributing editor to Bookanista. She has a doctorate from Princeton University and lives and works in London.

bookanista.com/author/mika/