After the deluge: Knowledge in the magical age of (mis-/dis-) information

by Mika Provata-Carlone

A new book by Simon Winchester has just come out. The mere fact in itself is thrilling and exciting. For over 50 years, Winchester has been critically informing his readers as a journalist for the Guardian, the Daily Mail or The Times, and as an author of political histories of troubled places and troubling times, or of lands of wonder and eras of promise; he has whisked them away to faraway regions as a writer for Condé Nast Traveller or National Geographic, or as the bewitchingly meticulous geo-historiographer of mighty rivers, volcanoes and seas; and he has sought to lure them into a life of insatiable questing after knowledge – and perhaps after wisdom – if not, to quote from one of his titles, after “the meaning of everything”, through books such as The Professor and the Madman, The Man Who Loved China, or The Map That Changed the World: The Tale of William Smith and the Birth of Modern Geology. His books are a formidable combination of technocratic precision (he did after all study geology at Oxford), and of highly idiosyncratic, aspiringly elegiac, sometimes volatile idealism. They can occasionally totter, as they struggle to maintain their balance between hard didacticism and superbly erudite munificence, yet they have invariably (or almost) captured the public’s interest and nurtured its imagination.

His latest book, Knowing What We Know: The Transmission of Knowledge, from Ancient Wisdom to Modern Magic, written at the now indomitable age of 79, after a life of prospecting ventures, high-octane adventures, even suspected espionage and confirmed near-catastrophes, seeks to rein in the question of why we ask questions at all. Why we know, what we know, how we know, and whether it all matters. How knowledge continues, travels across continents and time, passes from one generation to the next, transcends boundaries, cultures, and even paradigm shifts. More especially, at the heart of Winchester’s book there is the anxiety for the very survival of knowing, in a world where access to data and information has been both externalised and monumentalised, co-opted and maximalised by man-made tools which many fear might become independent agents and actors, a little like the mops and buckets of the sorcerer’s apprentice in Walt Disney’s Fantasia. Tools for which Truth capitalised may hardly matter, as long as the merely logarithmic statement true/false (as in on/off) may be answered either way. As Winchester starkly writes, “the problematic future of human wisdom is the reason behind this book’s very appearance in the first place.” More programmatically, Knowing What We Know “seeks to tell the story of how knowledge has been passed from its vast passel of sources into the equally vast variety of human minds, and how the means of its passage have evolved over the thousands of years of human existence.” It is both a strict and a tall order. And Winchester’s book succeeds brilliantly in supremely arousing and engaging our curiosity, as well as, strictly speaking, failing at times to fulfil its promises to the deeper level that they might perhaps deserve.

At its finest and strongest (i.e. the significant majority of its parts), Knowing What We Know will leave you gobsmacked – with its ideas, insights, titbits of unsuspected information, sparkling gems of real wisdom.”

Winchester’s style blends magnificence with easy eloquence, flowing storytelling with redoubtable observational powers. It has a lot to commend it, not least its tone of intimate conversation with the reader, even if, at times, the authorial voice verges on the authoritarian. At its finest and strongest (i.e. the significant majority of its parts), Knowing What We Know will leave you gobsmacked – with its ideas, insights, titbits of unsuspected information, sparkling gems of real wisdom. At its weakest, however, the book often morphs into a platform for the detailed showcasing of an essentially disparate, free-associative assortment of (individually) fascinating long segments of personal research which have captured Winchester’s attention, as well they might the reader’s. The result can seem inevitably hotchpotch, not infrequently forced, a mélange of critical reflection and a not always reflected display of erudition. It can even, at times, feel somewhat like a random paying of homage to wondrous figures and events glimpsed along a long life’s way. A little like a Victorian Miscellany of Extraordinarily Interesting Things.

More ponderous statements, such as “Aldous Huxley wrote in Brave New World of how humankind might one day fall in love with devices that help us not to think. His predictions appear to have strenuously taken hold. Might we then observe a lessening in our minds’ tendency to thoughtfulness, to consideration, to a reverence for learning? And if that were to happen, what might be the prospect for the development of wisdom?” are strewn across the book’s peregrination through history, geography, science and technology, politics and ethnosociology; frustratingly, however, they are not always given their full depth, weight and conceptual legroom. The tenuous thread running through the book is DIKW (more below), but the effort required to maintain one’s focus and to make sense of this at times far outweighs the rewards of the dialectical engagement, or even of the sheer intellectual pleasure that is unfailingly provided.

Winchester is fond of etymologies, categories and classifications, and of beautifully evocative quotations. The first contain, the second allow for what William Blake so memorably described in Proverbs of Hell as the vital overflowing of true understanding and creation. “The cistern contains. The fountain overflows” could well stand as Winchester’s very own authorial motto, and both Heaven and Hell form part and parcel of his discourse on Knowledge, Knowing, and above all their effect on and value for the Knower, i.e. our mere human selves (and, inevitably, the world we live in). The four “cisterns,” which somewhat floppily form the essential touchpoints of what can periodically feel like a “loose, baggy monster” of a book, are Data, Information, Knowledge and Wisdom, or the acronym DIKW, a key investigative structure for Theory of Knowledge (TOK) studies. To illustrate both the organic connection between the nodal elements of DIKW, and what Aristotle would call the meta ta physika, what lies beyond the mere materiality of things, Winchester calls upon the overflowing verses of T.S. Eliot in his later phase, once he too had found a way out of Waste Lands and the Prufrockean disenchantment and commodification of a life. He interweaves in his own analysis and ruminations a chorus from Eliot’s play The Rock (1934), and the lines will function as the single, primary lodestar of his periplous, becoming especially vital when his skies and horizons become obscured by ideological clouds or notional haze:

The Eagle soars in the summit of Heaven,

The Hunter with his dogs pursues his circuit.

O perpetual revolution of configured stars,

O perpetual recurrence of determined seasons,

O world of spring and autumn, birth and dying!

The endless cycle of ideas and action,

Endless invention, endless experiment,

Brings knowledge of motion, but not of stillness;

Knowledge of speech, but not of silence;

Knowledge of words, and ignorance of the Word.

All our knowledge brings us nearer to our ignorance,

All our ignorance brings us nearer to death,

But nearness to death no nearer to God.

Where is the life we have lost in living?

Where is the wisdom we have lost in knowledge?

Where is the knowledge we have lost in information?

The cycles of heaven in twenty centuries

Bring us farther from God and nearer to the Dust.

Winchester quotes this chorus in full, from the first verses which anchor the idea of displacement and dystopia, to those providing reason and causality, to the final ones, which voice, for Eliot, a damning conclusion and diagnosis. The latter is a terminus Winchester will both reflect on and, ultimately, question (as does Eliot). As Winchester launches upon his story, and what is essentially a process of comprehensive reckoning and of final judgement, Eliot comes to represent both the rigorous mechanics of intellection and the ineffable intangibility of real intelligence. Eliot’s chorus, Winchester tells us, surprisingly “helped to originate… [the] academic conceit known today as the DIKW pyramid,” and with Eliot as his own subtext, Winchester will embark upon a lengthy, circuitous, impassioned and highly personal meditation on “the interplay between the first three [compounds and] the relationship that all three enjoy with the ultimate […] concept known as wisdom.” It is a long essayistic exercise, bejewelled with all the fabled riches of a long life of thinking, travelling and researching, reporting and storytelling, but also fraught with the sense of a demagnetised compass – of a disoriented, or at least often disorienting, creative madness.

In part, this feeling of vision in blindness or blinded vision is due to the constant oscillation between the factual and the numinous, as well as the continuous recalibration of the narrative between perceived thematic centres and presumed civilisational peripheries. Also the unclear trajectory as regards periodisation and historisation, and narrative or argumentative progression on the one hand and, on the other, the aspirations towards formulating a philosophy of ideas concerning knowledge. From early on Winchester chooses a strategy of mind-mapping his account by way of selectionist pivotal moments or of equally preferential seminal figures in order to recreate what he has called at the onset the “uninterrupted process of ebbings and flowings” on which, in his view, knowledge and its transmission depend. Interspersed with these are long disputations on invariably fascinating, yet either tangential or fortuitously digressive topics, from technical analyses of inventions, to expositions on political events, to personal recollections which serve as evidentiary exempla. The result is a highly idiosyncratic consortium and collection, purporting to follow a geo-chronographic pattern and order of sorts, except that it frequently doesn’t, unless one keeps whispering the mantra DIKW softly and persistently in one’s mind.

Winchester’s loyalties and natural proclivities also appear to be constantly bifurcating: there is a staunch gravitation towards an Anglo-Saxon (and in particular British) centre of vision, cultural awareness and interpretation; a comparably profound grounding in, and admirable advocacy for a traditional genealogy of culture, from Mesopotamia and Egypt to Greece and Rome, to the European Middle Ages, the Renaissance and the cross-Atlantic and transcontinental Enlightenment, to the more global leaps of the Industrial Revolution and beyond; and, finally, a compunction to interpolate what are presented as ignored or marginalised narratives, such as Mesopotamian antiquity, or South American prehistory, which nonetheless, and contrary to this proposed schema, have long been standard topoi. China, ancient or modern, rather than Russia, India, Africa or the Islamic Arab world, features as the overpowering, towering Other, and the gaze vacillates between admiration and denigration, with a midpoint of unconcealed dread – of the unknown, or of the too-well known, as in the case of the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre.

Diderot and le Rond d’Alambert’s l’Encyclopédie was to public education what printing was to books: it made knowledge quite literally massively accessible.”

Following T.S. Eliot, two of the first influences on Winchester’s thought process to be thus introduced are Voltaire and Socrates. Voltaire’s involvement in the intellectual circle which was to create the first modern compendium of human knowledge, Diderot and le Rond d’Alambert’s l’Encyclopédie (coming some 800 years after the Byzantine Greek Suda composed in the 10th century), grants him a place among the pioneers of a new era of information-gathering and data-sharing, and of defining not only what or how much to know, but especially the very who-ness of the knowers. The Encyclopédie was to public education what printing was to books: it made knowledge quite literally massively accessible. The word encyclopaedia, Winchester affirms, comes from “the Greek enkyklios paideia (ενκύκλιος παιδεία), signifying ‘general education.’” In this and on other occasions, he is a little slipshod over proper lexicological definitions, and here it actually matters: enkyklios means comprehensive and all-rounded, not merely general. Encyclopaedias at their best were intended as affordable, shelfable, expert manuals of self-education, to have conveniently at home and for private use, to consult at one’s leisure and pace, as well as promising to be treasure chests filled to the brim with thrills and wonders. In Candide, Voltaire would conjure up such an awe-struck optimistic new learner (and in caricature his polymath teacher, Pangloss), as well as perform a near double-take. Posited as it is as the supreme Enlightenment critique of both abstractionist (and therefore arguably elitist) ratiocination and of religious institutions, the novel nonetheless issues forth an unyielding call-to-arms in favour of essentialist intelligence and of God, and especially, for that matter, of faith in God. God stays firmly in the picture, even when logic in its superb isolation seems to engage in an epic bras-de-fer with Logos,and all that this entails and presupposes.

For Winchester, Voltaire is Modern Man personified, of a rationalising modernity which still allows for a chink in the wall through which the divine may be glimpsed, a clear hint to contemporary readers, since God is there looking out from the wings in Winchester’s storyline as well. The crypto-immanence of the transcendental is one of the most seductive, but also perplexingly ambiguous realities in his writing, perhaps embodying the Pandora-like tenacity for Hope with which Knowing What We Know claims to end.

Compared to Voltaire, Winchester’s Socrates is a luminous figure in the shadows, half there and half spirited away. He is the voice of wisdom in Plato’s Theaetetus, where the conversation between an eminent logician and mathematician (Theaetetus) and the sage who loved to walk around the Athenian lanes and market streets, leads to a true turning point in intellectual history. Socrates seeks to understand what precisely takes us from the physiological perception of a thing, to the acknowledgement that we possess an inventoried identification tag for the thing perceived, and not only that, but we also know on solid grounds that we have reasons for knowing that a thing is what we believe it to be. It iswhat Winchester calls “the first consideration [of the question of knowledge, what it is, how it works, why it matters] in all of human history so far.” Socrates too kept God well in the picture. While he lived, he unfailingly listened to a daimonion, a divine voice which always showed him the way to true knowledge. Before he died, according to the accounts we have of his final hours, he yet again recognises one further level of knowing: in addition to the acknowledgement of human Logos, and of human limits and limitations (the one thing that we can know being, namely, that we know nothing), he also knowledges (in the original etymology of the word) the unknowable certainty in an eschatological, sacred reality. His final Justified True Belief statement applies to a cockerel he owes to Apollo.

The beginnings of Winchester’s story (and of humanity’s journey towards forging structures, customs and institutions of knowledge and learning) lie well before these two milestones of Western modernity and Greek antiquity, yet both Socrates and Voltaire, polarly different though they are, define the first essential conditions: the sense of wonder, the strength to question, the willingness to share, the strong feeling of belonging to and engaging with one’s community, the faith in a meaningfulness of things beyond the solipsism of the ego. It was such membership in a human group that started it all: the ecumenical, communally generated, and shared understanding and knowhow, the traditions of experiential learning which depended on societal gestures and rituals. Winchesterderives great relish in providing illustrations from contemporary non-historical societies, where their ancestrally innate apperception of the world and its phenomena have often given them a critical advantage over those supposedly ahead in technical progress. The transmission of knowledge especially in such societies allowed for more than physical survival: it made for essential survivance, “a continuation of tradition by way of the regular connection with the spirits of the tribal ancestors, a connection that helps keep ‘a sense of presence over time’”. It also provided the basis for community coherence. Interestingly, the organic continuity of tradition and community coherence are questions at the heart of contemporary debates on cultural identity, the need for, or the issues with multiculturalism and diversity and so much else, and perhaps a more fruitful discussion might emerge if they were more complexly and bilaterally examined in order to truly arrive at a dialectical polyphony rather than aiming for a simply different, and determinedly absolutist monophony.

Winchester’s deviations can be so engrossingly exhaustive as to feel at times meandering, haphazardly arranged or too selectively picked out from a larger pool of equally vital candidates vying for attention and inclusion.”

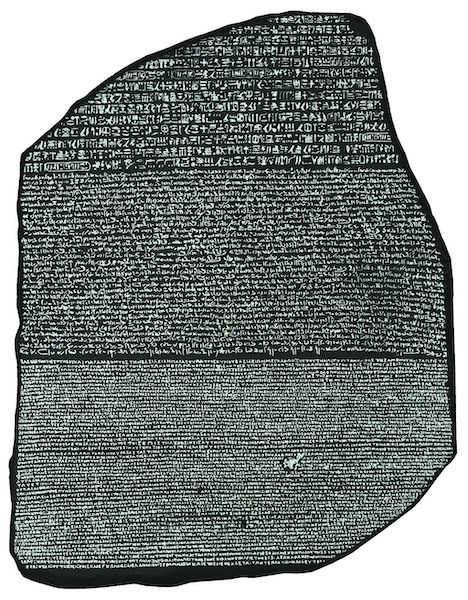

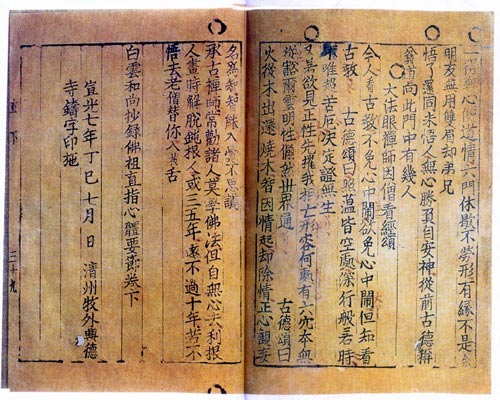

From his chosen starting point to his conclusion, Winchester proceeds throughout Knowing What We Know by way of deep flashbacks and proleptic leaps (his “ebbs and flows”). From communal learning-sharing, he will proceed to writing in its various forms and media, including considerations regarding factors which define or condition civilisational development: from geography and climate (papyrus), to cultural receptibility (scrolls vs. manuscripts vs. codices and printed books), socio-political or even economic structures, to sheer serendipity, which nonetheless must also be paired with ingenuity and a will for practical application (paper). His progression is steady, although deviations can be so engrossingly exhaustive as to feel at times meandering, and the selected waystations, although almost always cardinal, can occasionally seem haphazardly arranged or too selectively picked out from a larger pool of equally vital candidates vying for attention and inclusion. Stone inscriptions, for example, are given no space at all (barring the inevitable Rosetta Stone, which features in order to allow for a lament that the “man who knew everything”, the Englishman Thomas Young, was beaten by the Frenchman Jean-François Champollion in the race for its deciphering. That the Rosetta Stone has been in Britain since 1802 somewhat softens the blow). Nor is there any attention given to ancient or medieval messengers, as primary (and highly inventive) transmitters of knowledge (messages could be written on a shaven head, the hair regrowing between departure and arrival, and thus concealing the message), to town criers or, for that matter, to postal services, or more crucially the act of translation. The Press will get its fair share of glory and critique, even if political and ideological propaganda or indoctrination only receive a mild treatment.

Writing, whatever the medium, was the great civilisational earthquake. The first tablets were indeed storehouse inventories and accounting records, as Winchester richly recounts, but they also contained spells and curses, supplicants’ addresses to gods such as Dagon, haruspices’ readings, and soothsayers’ prophecies. As Winchester notes, they also bore testament to schoolboys’ efforts and the disciplinary measures which made such efforts successful. Some of the world’s first schools have been unearthed in Mesopotamia, a region which in its pre-Arab, pre-Islamic time, as Winchester notes, “was a highly educated corner of the early world, with schools that might well today be the envy of the current inhabitants.”

From Mesopotamia (where there is an unclear delimitation and dynamics between Babylonian, Akkadian, Assyrian, Hittite and Sumerian histories and stories), Winchester makes a precarious leap into the future, in a way which is indicative of many of the thrills but also of the significant failings of his model of history and the structure of his narrative. In a single stroke, a mirage-like linearity is constructed, topsy-turvy, time-defying, breathtaking, and profoundly questionable:

“Swept along with these tides [of rising and waning civilisations] were soldiers and traders and missionaries of one persuasion or other, so education itself began to be transported around the world from where its origin myths persuade us it all began. One can imagine the Roman legionnaires bringing the idea of schooling to their various outposts in Britannia and Gallia, Illyria and Iberia. It would be no stretch of the imagination to suppose that teachers would swiftly get to work clear throughout the Hellenistic world once Alexander the Great had spread his empire from the Indus to the Nile. Indeed, there is a little wooden notebook displayed in the British Library that comes from second-century Egypt. It shows the patient hesitancy of a local child doing his best to write and calculate – in Greek. Schools had already been well established along the Nile Valley, with hieroglyphic instruction for the Cairene nobility a prominent feature of Egyptian society for many hundreds of years. But here with this little string-bound loose-leaf notebook was education becoming global. Using a metal tool to scratch words and numbers onto a wax insert rubbed into a hollow on the wooden ‘page,’ the boy’s teacher writes a simple aphorism […] then has his pupil copy it out, just as the scribe in Nippur [in Hammurabi’s Mesopotamia] had demanded of his pupils (whip in hand, maybe) two thousand years before. […] The child’s trials show one thing incontrovertibly: education, exported from afar, was by now in full swing beside the Nile, with writing, numeracy and literacy at its core, an element of organised human life that was by now increasingly common everywhere within reach of the intellectual tentacles that had spread out westward from the banks of the Tigris.”

In one great leap, we have gone from Mesopotamia to Hellenistic Egypt, with Roman soldiers anachronistically interjected in between, and heading, no less, for what is now Great Britain, France, Spain and Albania. Herodotus’ immortalised Persia, or Minoan, Cycladic, Ionian, Athenian, Spartan, Theban, Stageirian Greece, Magna Grecia, Carthage, Etruscan Italy and Roman Rome and more, just simply do not appear. The troubling opacities of the term “intellectual tentacles” notwithstanding, this is a superbly stroboscopic conceptual braiding of distinct, and distinguished cultural strands, with a claim to a fantastically trompe-l’oeil factuality which might well appear irreproachable to the unsuspecting.

Yet between the Tigris of Hammurabi and Roman cultural translatio, there is a vast territory of reflected encounters, of original creation, reimagination and regeneration, of conscious analysis, and of redefinition of whatever cultural loan was initially involved in the process. Winchester sadly never addresses the fundamental question of what happens during that moment of cultural transference or, better still, at such a space of cultural crossroads, and more critically beyond it. From the Phoenician alphabet to the concepts and words, let alone the new forms of the letters these words and concepts were embodied in, in Greece or Rome, in Iberia, Gallia or Illyria, Hellenistic Egypt or Britannia, the distance is arguably as great as that between clay and potter’s wheel, and finished, glazed pot. Roman soldiers did transport the “idea of schooling” which they had absorbed from the Greeks (and reinterpreted, redesigned and reformulated according to their own Roman principles, values and cosmotheories) to their “various outposts”. Winchester’s strangulated historical survey, however, allows for and implies a very different coupling of concepts and genealogies.

The promoted suggested reading is that the Romans, having taken over the Hellenistic kingdoms of the Greeks, now became the vessels and the vehicles of Babylonian “ideas of schooling” and their so-termed “intellectual tentacles”. In a grand gesture of revisionist history, we are meant to see brought to the fore unjustly marginalised cultural groups, and to witness the redress of the mis-centredness of our chronology of civilisational consciousness. This is, however, staggeringly disingenuous: no educated mind across Western history would have ever presumed to either ignore these groups or deny them their primacy, as evinced, very significantly, by their earliest historians, the Greeks Herodotus and Xenophon. What Winchester’s magisterial slide reveals is that history today, cultural dialogue and civilisational polyphony often fall prey to (or must account for) a complacency of un-education, misinformation, and distortionist optics.

A traditional Western curriculum is invariably constructed so as to impart a sense of awe for a past which is seen as a constant dynamic presence – and which looks towards equally continuing enrichment. Anyone learning within this context will know exactly how the Sumerians, the Akkadians, the Babylonians or the Assyrians (or the Phoenicians and the Hittites) interacted with one another (often very bloodily, but also magnificently and inspiringly), and with others around them. Winchester’s sense of wonder at everything he has turned his mind to is in fact a case in point, as is the fact that his books never fail to have great hosts of readers. There has always been (no matter where one feels that one belongs) a sense of “looking through the eye of the beholder”, but that does not mean that the beholder is solipsistic, denialist or exclusionary. The “anxiety of influence” and the Animal Farm perspective of everything is, tragically, a contemporary predicament and pandemic, equally pervasive in academic and non-academic narratives of history today, yet neither were at play before quite significantly recent times.

That it is highly problematic to assume that de- and re-centring does not constitute a new, and troubling gesture of dominant and privileged perspectives is also evinced from Winchester’s next rhetorical attempt: “It is tempting to suppose that eastward tentacles brought Mesopotamian-style education to China, too. After all, the Antioch-to-Xian trade route we have come to call the Silk Road was connecting the two civilizations firmly from about the first century BC. Camel trains and caravans were plodding through the steppes of central Asia for hundreds of succeeding years, with merchants commuting on a regular schedule between the various capitals, bringing notions of their various cultures in tow, and doubtless contemplating teaching theirs to the others as part of their civic and national duties.” Once again notwithstanding the darkly perplexing repetition of “eastward tentacles,” China is off the hook, at least for now: “In fact, however, formal education had begun in China long before, without any apparent influence from the schools of the Near East, nor from anywhere else. […] Any outside influence on China was minimal to nonexistent.” Archaeological evidence, however, abounds of precisely such outside influence, in both directions. One can only wonder at the gallery of mirrors which seems to pop up as one looks at patterns, techniques, forms and representations; a little later Corinthian capitals found their way into Indian and Chinese architecture, and there are porcelain figures which mirror ancient Greek terracotta dancers. Byzantine textiles have Chinese motifs, as do Persian or Turkish ones. The wonder of encounters and the dialectical exchange they render possible is by no means the same as the ordeal of colonisation, appropriation or deculturation…

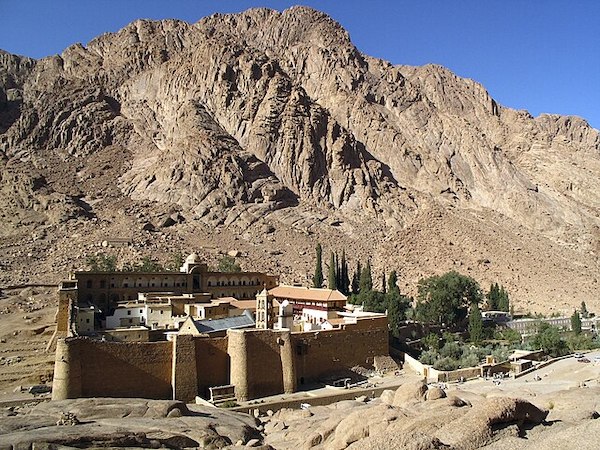

Libraries get a fair showcasing, though their history is truncated, and too far transposed into the future. The emphasis on cultural or political hostility towards them overshadows their centrality throughout time, from Mesopotamia through Greek and Roman antiquity, the Middle Ages and all the way to early and late modernity. Equally, key instances of catastrophic attacks by invaders on books and on a particular way of life are muted, such as the destruction of King Corvinus’ great library (second only to the Vatican Library in its time) by the Turks in 1526. Of its 2,000 irreplaceable volumes, only 220 survived, by virtue of having been exported earlier to other European countries, where they are still known as corvina. The desolation of the many libraries and book collections in Constantinople in 1453 is also silenced out. Monastic libraries East, West, North or South (Mont Saint-Michel? Saint Gall? Mount Athos? Canterbury? Ambrosian monasteries in Southern Italy?) are also skimmed over, except for a reminder that the finest (and oldest) is perhaps the one at Saint Catherine’s Greek Orthodox Monastery in Sinai.

Is curating printed or visual content a process which liberates and inspires the mind, or an interest-serving manipulation of the masses?”

Winchester’s account of encyclopaedias, however, and of the broader concept of easy-to-use, public-aimed, social-interest-focused containers of wonders of the mind or the senses, is one of the most absorbing and strongest points of his book. From private collections (often the result of Grand Tours, thus bringing home a mini version of that experience for the benefit of more than the original participants) to ambitious pangnostic projects such as the Mundaneum, to museums, to cheap instructional book collections, to Charles Babbage and his proto-computer (Ada Lovelace somehow falls through the cracks and into oblivion), to Wikipedia and Google, Winchester offers a galloping running commentary on their inception and their revolutionary impact. Yet he also points to the questions which must be raised regarding their power to alter and adulterate as well as shape and form, the ratio between material cost and social value, the debate on free or fee-paying access to culture, the virtues and pitfalls of ‘educating’ the public: is curating printed or visual content a process which liberates and inspires the mind, or an interest-serving manipulation of the masses?

The balance is precarious, the answer not as straightforward. Winchester makes his own argument by way of an example, in this case the Victorian practice of providing the non-privileged with carefully anthologised knowledge which had until then been presumably the prerogative of the few: “In the nineteenth century well-intentioned grandees who wished to nudge society away from religion toward the wider spread of knowledge made particular use of books that were wholly secular and, given the economies of scale brought about by the printing press, were affordable by everyone. The Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge was established in London in 1826 […] The SDUK, as it was known, was, much like books and newspapers, designed for what one might call the horizontal transmission of knowledge. There was no question here of adults informing the generation that would eventually come to succeed them. This was the educated nobility attempting to lift up their less well-schooled kinfolk, for the benefit and betterment of all. This was an exemplar of what was to be called the March of Mind – a furious debate that took place in the early nineteenth century with those who felt that knowledge ought to be ever more widely spread, that understanding should not be a monopoly of the ruling classes but that all had the absolute right to know all. Opponents of this view – and there were many, and they were loudly vocal – complained bitterly that to educate the lower orders would bring havoc to society, that the steam engine and the industrial revolution were to blame for such a noxious idea, which would only encourage mischief and riotous behaviour among the working classes. […] the March of Mind would usher in that bogeyman of the conservatives, progress” – and what were seen, then and now, as its many discontents. The fact that progress has somehow always been nurtured by true conservatives is a point for a longer conversation which Winchester sets aside. Lord Henry Brougham’s Library of Useful Knowledge, a collection of cheap slender booklets on various subjects, would also expand to include a Library of Entertaining Knowledge, and the SDUK’s Penny Magazine.

The neurophysiological nature of learning and memory (emotive and factual) opens up the terrain to significant gnoseological questions: if we do not need to remember everything, are we still capable of learning, of creative, critical, original thinking? Do too many facilitating tools atrophy the mind? What is the truth-value of the products of such tools as they evolve with ever greater speed and exponentially more massive complexity? As he writes, “technology has now advanced in such undreamed-of speeds and directions that humanity’s very mental existence must be considered to be at risk. What can and may and will happen next to our mental development if and when we have no further need to know, perhaps no need to think? What if we are then unable to gain true knowledge, enlightenment, or insight – that most precious of human commodities, true wisdom? What then will become of us?” The first spell-checkers for the newly devised electronic word processors would appear to load the dice in a particular direction in the Technology vs. Humans debate, as claimed by a famous ditty of the time:

Eye have a spelling chequer,

It came with my Pea Sea.

It plane lee marks four my revue

Miss Steaks I can knot sea.

Eye strike the quays and type a whirred

And weight four it two say

Weather eye am write oar wrong

It tells me strait a weigh

The irreducible pragmatic logicality of the parts in isolation, the irrefutable surreal nonsense of the whole, felicitously lead on to what is Winchester’s centre of analytical and narrative gravity, namely the debate between human acquisition, production, processing and use of data, information and knowledge, and what we have come to term ambiguously and perhaps unreflectedly Artificial Intelligence. The wonders of hyper-textuality, virtual reality and the mass appeal and reach of the internet, as well as the unharnessed sovereignty these have granted to the Press and the Media as they disseminate both real and fake news; self-mythologising, and the culture of narcissistic (and totalitarian) autoctisis; the sheer thrill and very real substance of Google and Wikipedia (and their own pitfalls of potential falsification and unverifiability); the near-prestidigitatory magic of GPS gadgets and SatNav systems; the power of AI (first formulated by the son of ardent communists, who was raised on Soviet science books and Vienna Circle formalist ideals, before turning ardent Republican) to support research in technology, theoretical science and the life sciences, but also to pervert the significance of the data it works with; all these give occasion for a grand, sweeping tale (or several, for that matter, including Winchester’s real-life real-watch Rolex Moment). They more crucially allow Winchester to bring together 70-odd years of mature reflection and problematisation, of socio-political concern and experimentation, of life, more simply, and to ponder hard.

Winchester’s concern is not so much that humans will be replaced or eradicated – but whether, by delegating all cognitive or sentient processes or even practical tasks to AI, they will be reduced to a state of total idiocy, and therefore Darwinian redundancy and natural extinction. It is a dystopic vision the West has confronted before, perhaps most poignantly in Jonathan Swift’s tale of the Houyhnhnms and the Yahoos. It is tantalising to think that behind Swift’s Houyhnhnms, the supreme equine beings whose logic is so pure, so clinically rational, as to be terrifyingly and lethally absurdist, lies the Greek word distinguishing animals from humans, alogon, namely that which is devoid of speech, but also of reason. Swift had a thorough scholastic grounding in both Greek and Latin, and from the Hellenistic times onwards, alogon would be an alternative term for horse in Greek. The Houyhnhnms’ ultimate civilisational scheme foresees a world from which the Yahoos, the bestialised humanoid creatures who serve as the labour force (or worse) in the Land of the Houyhnhnms, will be totally exterminated.

Is AI the Houyhnhnm equivalent of the digital age? And are we willingly or even elatedly converting ourselves into growling yet submissive Yahoos? The implicit argument in Knowing What We Know is that our very fascination with scientific objectivity might be at the root of our subjection, and likely catastrophic transmogrification. There is a perverse Rousseauism inherent in the entire AI debate as it currently stands, with AI taking over the role of the noble savage who must be allowed to grow and flourish unhindered by the conventions and strictures of a human society. We observe mouths agape, minds in awe as AI evolves, devolves, performs unimaginable tricks of mental acrobatics before our very eyes. Yet the question we should ask is arguably not “what can AI do,” but “what do we feel it ought to do.” The answer, implicit in Winchester’s line of thought, although he does not ask the question directly, is simple. AI ought to be a perfect tool, in the hands of invariably imperfect humans. It should be not merely needs-driven, but conditional to an ethics of wisdom, rather of suprematist knowledge, an ethics of philosophically understood individual and social eudaemonism.

This is the unmistakable thrust behind Winchester’s conclusion, which oversteps the signs of darkness and foreboding to voice rather a plea for hope. He drops a hint for us, namely Rudyard Kipling’s principle of ’Satiable Curiosity from his story The Elephant’s Child, and for those who have not read the story, the hint might well remain a cryptic one (that Winchester drops Kipling’s apostrophe from the word Satiable does not help either). The Elephant Child’s curiosity is not satiable, but insatiable, and he ignores all injunctions (supplemented by laborious spanking) to follow the Augustinian tenet of “I no longer wished to read further.” He almost loses his life as he seeks limitless knowledge, and only escapes thanks to the help of the Bi-Coloured-Python-Rock-Snake, who comments memorably “Some people do not know what is good for them.”

It is knowing where to stop wanting to merely know, because of a deeper understanding of what is good, which defines wisdom, and Winchester will override the eminent experts of the London Centre for Evidence-Based Wisdom, and their project to provide scientific delimitations and parameters, in order to make his own point on that question. The thirty experts had concluded that although “a person who was neither spiritual nor intelligent was unlikely to be wise,” wisdom is ultimately a measurable, though rare, cognitive and emotional state, which is both learnable and age-cumulative, though not pharmaceutically achievable. There is no pill for it. It is a reductionist, Houyhnhnm abstraction of a quality that defines the very essence of our humanity, culturally, historically, spiritually and ethically. To counter this de-fleshing of the meaning of existence, Winchester calls upon his final pair of seminal minds – and lives.

“Before all of this, however, before the Renaissance, before the Enlightenment, before the industrial revolution, before Galileo and Newton, Milton and Einstein and Tim Berners-Lee (but after Plato and Socrates), there was Aristotle and there was Confucius. […] The influence of each has been profound and enjoys a peculiar longevity, making it likely that Aristotelian and Confucian will come to signify schools of thought and affect and moral rectitude that will exist so long as humankind remains capable of civilized behaviour. […] Confucius laid down rules; Aristotle opened doors. Whereas Confucius suggested the existence of the tao, the way to right behaviour, Aristotle showed how virtuous living can and should lead to what so many Greek philosophers famously called eudaimonia, happiness.”

During a memorable plane journey, another figure, a Dr Agrawal, had taught Winchester that Aristotelian eudaimonia is commensurate with true ethical behaviour – or as Socrates, the originator of that principle put it, there is only one free choice, the choice of the good. Christianity would later come to claim the same.

Between allowing for something beyond our mere mortal ken, and perhaps acknowledging that we may well know nothing, lies a journey across human experience and time as Winchester sees it – an Odyssey, as he indirectly calls it, with varied stops, monsters and sirens. Throughout this journey lies the sheer delight of discovery and understanding, the encounter with the unknown and the unknowable, as well as with the terrifying, and very frequently with simple human fallibility and the limits of mortality. And at the end of it? At the end of Odysseus’ peregrinations and, one hopes, at the conclusion of our enthralment with the exotic, Circean potential of AI, is a familiar Ithaca, a world of satiable rather than insatiable curiosity, rendered meaningful and now consciously cherishable through a process of encounters which are critically processed, and act as reminders that what we already have is often the only thing that truly matters. These Odyssean encounters progressively help us recover (nostos), rather than traduce our humanity. Knowing What We Know delivers at least that much (and certainly more): a summons and an appeal to remain human, to cherish what has sustained us for as long as we can remember, to continue growing in our living traditions, while harnessing AI for the needs but not the meaning of life.

—

Simon Winchester grew up beside the Atlantic in southwest England and studied geology at Oxford. He is the bestselling author of The Man Who Loved China, A Crack in the Edge of the World, Krakatoa, The Map That Changed the World, The Surgeon of Crowthorne (a.k.a. The Professor and the Madman), The Fracture Zone, and many other books. Awarded an OBE in 2006, he lives in western Massachusetts and New York City. Knowing What We Know is published by William Collins in hardback, eBook and audio download.

Read more

simonwinchester.com

@simonwwriter

@WmCollinsBooks

Mika Provata-Carlone is an independent scholar, translator, editor and illustrator, and a contributing editor to Bookanista. She has a doctorate from Princeton University and lives and works in London.

bookanista.com/author/mika/