Alice Munro: ‘Menesteung’

by Suzanne BerneOne of the reasons to write about the past, it seems to me, is to try to save someone or something from obscurity, or as Alice Munro says in ‘Menesteung’, from her collection Friend of My Youth: “to rescue one thing from the rubbish,” to “see a trickle in time.” This is that kind of story.

It’s set in Canada, like so many of Munro’s stories, in a small rural town; the Menesteung is a nearby river. Our unnamed narrator has been poking around the local library and comes across a little book of sentimental poetry titled Offerings, published in 1873, the work of a very minor Canadian poetess named Almeda Roth – who has been all but forgotten save for a few mentions in back issues of the local paper, probably stored now on microfiche. Almeda Roth was a nobody, a fussy old maid, a bad poet. Hardly worth notice. Until the narrator decides to start noticing, to pay attention to the rough 19th-century world in which Almeda lived and how she lived there, what she must have cared about, been passionate about.

Structurally, this story works by leaps of conjecture. The narrator has a limited amount of information, mostly garnered from the library, but she uses each shard of it as a kind of raft to sail into the past. She’s got a photograph of Almeda, printed inside Offerings; there’s Almeda’s own treacly preface to her collection (in which we discover that her parents and siblings are all dead); the poems themselves; old issues of the town newspaper, the Vidette. Most of all, there’s the narrator’s own tremendous interest in wresting from the river of history this one insignificant human being.

Here she is on the photograph of Almeda:

“The poetess has a long face; a rather long nose; full, sombre dark eyes, which seem ready to roll down her cheeks like giant tears; a lot of dark hair gathered around her face in droopy rolls and curtains. A streak of gray hair plain to see, although she is, in this picture, only twenty-five. Not a pretty girl but the sort of woman who may age well, who probably won’t get fat. She wears a tucked and braid-trimmed dark dress or jacket, with a lacy, floppy arrangement of white material – frills or a bow – filling the deep V at the neck. She also wears a hat, which might be made of velvet, in a dark color to match the dress. It’s the untrimmed, shapeless hat, something like a soft beret, that makes me see artistic intentions, or at least a shy and stubborn eccentricity…”

And with this marvellous eye for detail, and even more marvellous sense of what to make of it, the narrator goes on to describe the town itself, part of what was then called Canada West, treeless, hardscrabble, dusty, “bare, exposed, provisional-looking.” Full of stray dogs, pigs, cows that get loose from their tethers. A wholly convincing portrait, but then she offers this odd disclaimer: “I read about that life in the Vidette.”

A statement which, of course, establishes her authority. She’s going to be making up a lot, but she has some basis for all her conjectures and suppositions. She’s starting from the known to venture into the unknown, the world of late 19th-century provincial Canada. Soon she moves from contemplating the whole town to Almeda Roth’s corner of it, the corner of Pearl and Dufferin Streets, where her house is poised between the respectability of Dufferin Street and the Pearl Street Swamp. Enter a love interest in the form of Jarvis Poulter, salt merchant, who lives next door. Our narrator is now starting to excavate Almeda’s emotional life the way Jarvis excavates salt from below the earth. And yet, weirdly, wonderfully, at this point in the story the narrator exits. Her presence still registers in occasional asides, but the personal pronoun vanishes. This story is now Almeda’s.

The Vidette, meanwhile continues to supply commentary, acting as a kind of Greek chorus:

“Among the couples strolling home from church on a recent, sunny Sabbath morning we noted a certain salty gentleman and literary lady, not perhaps in their first youth but by no means blighted by the frosts of age. May we surmise?”

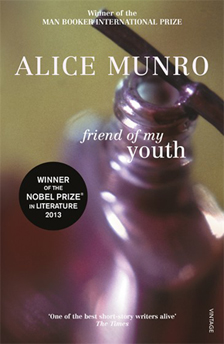

Detail from the Canadian Penguin Modern Classics edition of Friend of My Youth

Well, if no one else is going to surmise, our narrator will. Meanwhile, she’s also still filling in this place, which is of as much interest to her – or more – than Almeda herself, a “raw countryside just wrenched from the forest.” Within the town, trying so hard to be civilised, there are brawls in the night on Pearl Street, overheard by Almeda. On one night in particular she half-witnesses brutish consensual sex, a scene all but unimaginable to our minor poetess. In fact, she assumes she’s overhearing a murder, and runs barefoot, in her nightdress, to Jarvis Poulter’s house for help. The narrator is utterly subsumed in the story now. No more commenting on comments in the Vidette as we arrive at Munro’s real concern, to show us that the past is full of violence, sex, lust, death – even the past of a prissy poetess who lived in a house with lace curtains and baked overelaborate cakes. Her house, after all, looks onto a swamp full of danger, depravity, foul smells and disgusting sights – a true ‘Gypsy Fair’, the title of one of her sentimental poems. And it is when Almeda finally becomes part of the mess of life that Jarvis Poulter is “sufficiently stirred” to imagine her as his wife.

This is the turning point, when the story could have gone another way. History could have turned out differently, Almeda might have become Mrs Poulter. Jarvis Poulter knocks on her door later that morning to escort her to church, but Almeda refuses to answer. To calm her nerves after her upsetting night, and to soothe her menstrual cramps, she takes laudanum instead and slips into a kind of ecstatic madness. And now the story becomes truly breathtaking as pale unassuming Almeda Roth, already going grey at 25, transforms into a marvellous figure of passion and artistic ambition, of madness and supreme sanity, a woman whose mind is a great river of rapids and eddies, though she lives in a world of crocheted table runners and wax fruit. Meanwhile her rescuer, the narrator – who knows only a few details of Almeda’s life and where she is buried – has found a lost woman and a whole lost world, and Munro has written one of the most brilliant stories I’ve ever read.

Suzanne Berne‘s first novel A Crime in the Neighborhood won the 1999 Orange Prize. She has since published the novels A Perfect Arrangement and The Ghost at the Table, and the memoir Missing Lucile: Memories of the Grandmother I Never Knew. Her latest novel The Dogs of Littlefield is published in the UK by Fig Tree. She teaches creative writing at Boston College and is on the faculty of the Ranier Writing Workshop in Tacoma, Washington.

Suzanne Berne‘s first novel A Crime in the Neighborhood won the 1999 Orange Prize. She has since published the novels A Perfect Arrangement and The Ghost at the Table, and the memoir Missing Lucile: Memories of the Grandmother I Never Knew. Her latest novel The Dogs of Littlefield is published in the UK by Fig Tree. She teaches creative writing at Boston College and is on the faculty of the Ranier Writing Workshop in Tacoma, Washington.

suzanneberne.net

Read Lucy Scholes’ interview with Suzanne in this issue.

Alice Munro was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2013 and won the Man Booker International Prize in 2009 for her life’s body of work. Born in Huron County, Ontario in 1931, she is the author of over a dozen short-story collections, often set in her home county. Friend of My Youth is published in the UK and the US by Vintage, and in Canada as a Penguin Modern Classic.