An alternate story

by Gina Apostol

“At once a murder mystery, a war movie, and a moving exploration of all the ways grief lives on, both in a people and in a person. A masterful puzzle.” Elaine Castillo

It turns out Chiara is a member of a group of Hollywood types who gather every few years or so in the Catskills. In a woodsy agricultural setting, Chiara’s group plays parlor games and captures ghosts in séances and commands lunar apogees and exhibits all sorts of megalomaniac tendencies, in small and unreported doses, usually in April, the cruelest month only if you are a poet, not a millionaire.

At one of the revels, Chiara’s cabal gathers for lunch at the giant liver-shaped kitchen table in the eighteenth-century manse owned by Chiara’s mother, a dreamer in constant convalescence whose absence from her mansion goes unremarked. The artist guests spontaneously carry in their arms, as if lifting ritual Byzantine icons, their identical fifteen-inch, quad-core, silver MacBook Pros.

People barely look at each other or even check the wine list (one of them has been in AA since age fourteen). Instead, they all begin typing memos or searching the difference between heirloom or heritage apples or opening their email at the same audible incredible momentous freaky time! Snapping her head up at the moment when everyone else understands that the room has just exploded into one eerie propulsive click, all together, twenty-first-century robots come to life – Chiara laughs.

They begin to eat the free-range duck confit with organic pea shoots and Roxbury Russet compote (heirloom, not heritage) and drink the local cabernet franc, which has no sulfites. But a pall comes over the afternoon, though no one mentions it.

Perhaps only Chiara had this recognition that something terribly gauche had just united them, wistful, emerging auteurs. After dessert, still sipping espresso, the group comes up with a parlor trick. It occupies them for the next few days, in between yoga and once again watching Mulholland Drive.

Each moviemaker chooses a search term, and from information produced by a single Google search – from the Web’s constraint – each will write a movie script.

***

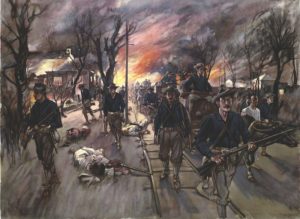

20th Kansas Volunteers marching through Caloocan at night, 1899. Harper’s Pictorial History of the War with Spain, Vol. II (Harper and Brothers). Wikimedia Commons

There is always an alternate story – so Chiara’s search reveals.

It turns out a Filipino scholar has written a paper linking the massacre of civilians in Balangiga, Samar, 1901, to the 1968 Vietnam massacre that frames her father’s film. As some viewers might recall, The Unintended is a memoir, or as the Guardian describes it, “a sterile mystery wrapped in spiral flashback,” about a teenage kid, Tommy O’Connell, who fails to be court-martialed for acts he has committed in a South Vietnamese hamlet, code-named Pinkville (the name of the actual village is never mentioned). The boy Tommy, along with his fellow soldiers of Charlie Company, razes the hamlet to the ground. He tells his story so that the world does not forget the horror he, Tommy, cannot leave behind.

The Balangiga incident of 1901 is a true story in two parts, a blip in the Philippine-American War (which is a blip in the Spanish-American War, which is a blip in latter-day outbreaks of imperial hysteria in Southeast Asian wars, which are a blip in the infinite spiral of human aggression in the livid days of this dying planet, and so on).

Part One: An uprising of Filipinos against an American outpost in Samar (the exposition here would be a fascinating movie in itself, though with too many local color details) leads to forty-eight American deaths, with twenty-two wounded and four missing in action.

I want no prisoners. I wish you to kill and burn. The more you kill and burn, the better it will please me. The interior of Samar must be made a howling wilderness.”

Part Two: The US commanding general demands in retaliation the murder of every Filipino male in Samar above ten years of age. Blood bathes the province. Americans savage – “kill and burn” is the technical term – close to thirty thousand Filipinos, men, women, and children, in a rampage of such proportions that the court-martial of the general, Jacob H. ‘Howling Wilderness’ Smith, causes a sensation when the events become public in 1902.

The scholar, Professor Estrella Espejo of the University of the Philippines in Diliman, points out that the Samar incident also implicates a Charlie Company (though of the wrong regiment, the historic US Ninth Infantry, the Manchu Fighters, a glamour brigade). And as in the Vietnam incident (and in other similar times, e.g., in Afghanistan and Iraq), barely a handful of Americans are tried for the homicidal affair.

Filipino casualties on the first day of Philippine-American War, 1899. National Archives/Wikimedia Commons *

The infamous General Jacob Smith ordered the Filipino deaths by making memorable staccato statements: “I want no prisoners. I wish you to kill and burn. The more you kill and burn, the better it will please me.”

The general’s resonant phrase made his name: “The interior of Samar must be made a howling wilderness.”

According to Professor Espejo, the repulsive yet fascinating Smitty Jakes, the Kilgore-like lieutenant whose pathological patriotism is the most troubling yet truest aspect of Ludo Brasi’s film, is a nod to the butcher of Balangiga.

The movie’s hero, the guilt-ridden wraith Tommy O’Connell, Espejo concludes, resting her case, is clearly the West Point–educated commander of the Samar outpost, twenty-six-year-old Captain Thomas W. Connell, a moralist whose meager ethics measured in full the absurdity of the American cause.

from Insurrecto (Soho Press, UK paperback £12.99, US/Canada hardback $26/$32. Also in eBook and audio download)

* The original US Army caption reads: “Insurgent dead just as they fell in the trench near Santa Ana, February 5th. The trench was circular, and the picture shows but a small portion.”

Gina Apostol’s first two novels, Bibliolepsy and The Revolution According to Raymundo Mata, both won the Juan Laya Prize for the Novel (Philippine National Book Award). Her third book, Gun Dealers’ Daughter, won the 2013 PEN/Open Book Award and was shortlisted for the William Saroyan International Prize. Her essays and stories have appeared in The New York Times, Los Angeles Review of Books, and other journals and anthologies. She grew up in Tacloban, Philippines, and lives in New York City and western Massachusetts. She teaches at the Fieldston School in New York City. Insurrecto is published by Soho Press.

Gina Apostol’s first two novels, Bibliolepsy and The Revolution According to Raymundo Mata, both won the Juan Laya Prize for the Novel (Philippine National Book Award). Her third book, Gun Dealers’ Daughter, won the 2013 PEN/Open Book Award and was shortlisted for the William Saroyan International Prize. Her essays and stories have appeared in The New York Times, Los Angeles Review of Books, and other journals and anthologies. She grew up in Tacloban, Philippines, and lives in New York City and western Massachusetts. She teaches at the Fieldston School in New York City. Insurrecto is published by Soho Press.

Read more

ginaapostol.com

@GinaApostol

Author portrait © Margarita Corporan