At the museum

by Maki Kashimada

The glass door slid open without a hitch. That was only natural, the woman realized. They were automatic doors. She glanced around the main entrance. The building was immaculate, and looked to have been designed with considerable attention to architectural aesthetics. It reminded her of a hospital. Whiteness and curves. She wondered whether people associated such things with peace.

She found the entrance at the bottom of a spiraling slope.

There, she bought a ticket, and made her way to the automatic entrance gate. The room beyond was shrouded in darkness. The woman hesitated. It wasn’t like the museum in Hiroshima. The Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum displayed various objects in glass cases arranged in brightly lit rooms, things like clothes worn by survivors of the atomic bombing. The Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum, however, felt almost like entering a choreographed stage production.

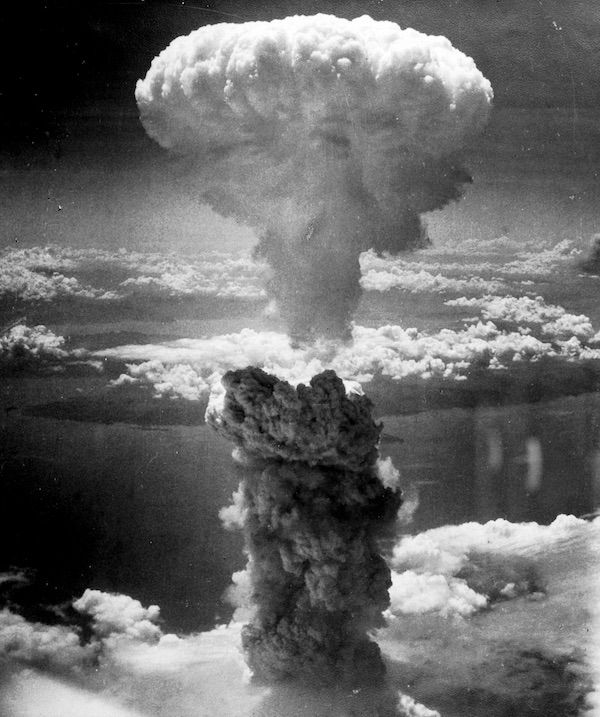

She stepped gingerly through the automatic ticket gates. It was dark inside. She could hear the loud sound of a clock ticking. Uneasiness fell over her. A clock in an illuminated display. It was broken. The hands pointed to 11:02, the minute that the atomic bomb was dropped. That alone was enough to explain its significance. The exaggerated sound of the ticking clock. Fear took hold of the woman. She escaped to the next room.

The space was dimly lit, as though by an old miniature light bulb. Photographs of the city of Nagasaki and Urakami Cathedral in the immediate aftermath of the attack. Lots of digital monitors. Dead bodies appeared on the screens, testimonies and diary entries from that day. She could still hear the ticking of the clock. The woman’s anxiety didn’t abate. A statue of Christ rose up in front of her. She was afraid. She suspected that she might be killed by that statue. It didn’t occur to her that the atomic bomb would kill her.

The woman was struck with relief when she entered a normal room free from those special effects. She looked over a model of the city of Nagasaki. It was well made. As she approached the model, a recording began to play. The city of Nagasaki, August 9, 1945. Population: two hundred and forty thousand. Number of deaths caused by the blast: seventy-three thousand eight hundred and eighty-four. Number of injured: seventy-four thousand nine hundred and nine. No sooner did the voice read the numbers out than it disappeared. The model lit up in concentric circles. Those circles, representing the damage caused by varying degrees of radiation, spread across the city. The woman was fascinated by them, so beautiful and precise.

Glancing around the room, the woman caught sight of a number of children dressed in school uniforms. One of them was hugging a full-size model of the Fat Man bomb. Hey, this thing’s cold, he said. It’s nice and cool.

In the glass cases by the walls were a photograph of a woman’s burned back, a steel helmet with pieces of a skull stuck to it, and other displays. It was the same as what she had seen in Hiroshima. There was a melted soft-drink bottle next to a placard indicating that visitors were free to touch it. The glass was twisted and distorted. It was cold to the touch. The temperature that glass is meant to be. Nice and cool. She realized that she was sharing the same impression as the child hugging the Fat Man replica a moment ago. It was cold. At this point in time, that was. In any event, this point in time was all that the woman could understand.

You said you came to this land to witness the thirst of six thousand degrees for yourself. Maybe here, you thought, you could lay eyes on that invisible thirst.”

The woman returned to the hotel shortly after noon. She made her way to the youth’s room.

I went there. To Urakami.

The woman pressed herself against the youth’s chest, slowly pushing him down onto the bed.

I saw what Nagasaki looked like that day, recreated by the Japanese.

The woman pressed her lips against the youth’s chest. They’re cold, he said. The two of them stared into each other’s eyes.

It was Nagasaki, exactly as the Japanese saw it.

The two pressed their lips together.

They’re cold. Your body is cold too.

The youth pulled the woman close.

It’s the air-conditioning. That’s why spring is so cold in Nagasaki.

I heard it was already hot and humid that day, before it was dropped.

It was so cold in the museum too. I felt a chill, but I don’t know whether it was because I was scared, or because of the air-conditioning.

Did you see the people with all those burns?

I saw a woman’s festering back. But it wasn’t only people who were burned. There were six soft drink bottles melted into one. An ivory seal that had swelled up like someone’s big toe. There were so many things that represented heat. I saw them all. One after the other. I could feel my head becoming more and more inorganic. My flesh turned cold. I couldn’t even visualize heat anymore.

But you said you came to this land to witness the thirst of six thousand degrees for yourself. Maybe here, you thought, you could lay eyes on that invisible thirst.

That’s right. I wonder if my heart is festering like that woman’s back. I wonder if the contours that define me have melted away like those of the soft drink bottles. I wonder if I’ve been warped like that ivory seal. I don’t know. Sympathy? Because those things turned my heart cold and white. They swept away everything that my heart tried to compare them to.

What did you see in the museum?

I saw a tragic story, a story that rejected my whole existence. The Japanese describe that day so tragically, you know?

It was tragic. They’re only describing it faithfully.

It’s such a strange feeling. My mind was filled with tragedy when I came to Nagasaki, and other things too. But when I stood in the museum, I forgot all about them. That place has the power to render you unconscious. So I couldn’t remember what else I had been thinking about, apart from tragedy. If not tragedy, then sorrow, maybe? Or madness? Those too can be like an atomic bomb.

extracted from Love at Six Thousand Degrees, translated by Haydn Trowell (Europa Editions, £14.99)

—

Maki Kashimada is a multi-award winning novelist well known for her avant-garde style. She is the author of Two, which won the 1998 Bungei Prize, and Touring the Land of the Dead (Europa Editions, 2021), winner of the prestigious Akutagawa Prize. Love at Six Thousand Degrees was awarded the Yukio Mishima Prize, for work that “breaks new ground for the future of literature’, and is now published by Europa Editions in paperback and eBook.

Read more

@EuropaEdUK

Author photo © Shinchosha

Haydn Trowell is an Australian literary translator of Japanese fiction. His translations include Touring the Land of the Dead by Maki Kashimada, The Forest Brims Over by Maru Ayase and The Rainbow by Yasunari Kawabata.

@haydntrowell