Ami Rao: All life is here

by Mark Reynolds

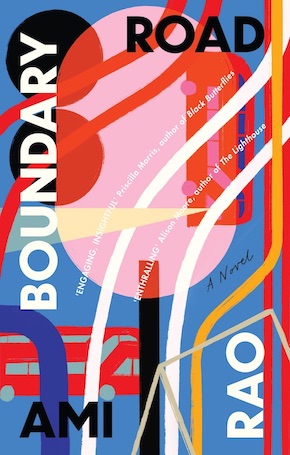

Ami Rao’s Boundary Road is an inventively structured, deftly observed and uncompromisingly raw snapshot of contemporary multicultural London in which two young passengers on the Number 13 bus from central to north London have fleeting encounter whilst lost in their own pasts. Aron is making a new start as an assistant in a suit shop, embarking on a life beyond the gangland scene that once defined him, and chats brightly to anyone within earshot, gathering their stories. Nora, who is trying to make ends meet as a hotel chambermaid while shaking off the recent advances of a repugnantly insistent guest, is more circumspect but keenly aware of interactions between her fellow travellers. Their fortunes cross when another young man who has joined Aron presses the emergency button above the rear doors and they both scramble off the bus. The scuffle continues minutes later at the edge of Nora’s estate as she’s walking home, until finally Aron and Nora are face to face…

Mark: What drove your decision to use the timeframe of a single bus journey, and begin the narrative from the viewpoints of two random passengers?

Ami: For me, literary voice (or in this case, two voices, Aron and Nora) comes first and everything else follows. Once I’d found my two voices, I wanted Aron and Nora to notice each other but not to meet, and the bus suited my purposes in that regard. It’s a place where so much human drama unfolds yet one can choose to be a part of it, or not. That was my first motivation. Second, after I’d established that I wanted the narrative to be told from two simultaneous points of view, I wanted to write every flashback, conversation or thought as a ‘moment in time’ while still creating a kind of awareness in the reader that time doesn’t stop, we are in perpetual forward motion… until we are not. So, setting the story on the bus worked for me, both logistically and metaphorically. The bus makes multiple stops along the way, people come in, people get out, but the bus itself keeps moving until the end of the route. Like life.

At what point did you decide to write a novel that ‘ends in the middle’, with the second part of the book looping back to the defining moment?

This was a creative decision about the shape of the book that I made pretty early on. Boundary Road is a work of art, but if you take away the abstraction, it is ultimately about knife crime. The novel ends in the middle as a tiny gesture of resistance to closure. Philosophically speaking, the story cannot end until the unbidden violence underpinning it also ends.

Reading between the lines in your Acknowledgements, did the naming of Nora come after it was pointed out to you that it spells Aron backwards? It’s satisfying that ARON:NORA meet in the middle in the same way that their stories overlap.

Aron and Nora both came to me at the same time. I was visiting my friend Nora in Maida Vale when I received a text message from my friend Aron. I told him where I was and that’s when he pointed out the ARON:NORA thing. I’d say that was probably the genesis moment for the entire novel. It immediately gave me a structure, a sense for the architecture of the book. Sometimes that’s all it takes to spark an idea – an observation, a coincidence, an incongruity, a puzzle that floats around in your head, and doesn’t go away and you feel compelled to do something about it. Write a book or whatever.

I think to be a novelist, you’ve got to have a certain curiosity about other people’s lives and ever since I can remember, I’ve been endlessly fascinated by total strangers.”

On first reading it’s a bit of a leap of faith to believe that Aron would have quite so many animated conversations with strangers on a single bus ride, but it does reflect how we all carry multiple memories/stories in our heads at any given time, that can be sparked by incidental interactions, conversations and observations. It also evokes how Aron’s senses are heightened at this particular moment when his past, present and hopes for the future collide…

I wrote Boundary Road entirely during Covid and the multiple conversations are probably a projection in opposition to the experience of the unnatural isolation we were all a part of. If you trace the development of the novel over time, you can see how it tends to be a reflection of, or a reaction to, the time it is set in, and my response to that moment in time was to produce a polyphonous novel. George Orwell wrote in his wonderfully funny ‘Why I Write’ essay that a lot of novels are written out of some kind of desire to fix things or right some kind of perceived wrong. I guess that’s what I was doing – all totally subconscious of course.

Are you a prolific taker of notes as you travel around London (and elsewhere)? To what extent do peripheral, overheard conversations pique your curiosity and fire the imagination? There’s one particular broken-off phone call in the book that I really hope you actually overheard – where Aron realises that “sometimes you don’t have the faintest idea what someone is talking about. And of course, the chances are that you will never find out.”

I don’t take notes, I wish I was that meticulous, but I do eavesdrop! All the time and with great enthusiasm! I think to be a novelist, you’ve got to have a certain curiosity about other people’s lives and ever since I can remember, I’ve been endlessly fascinated by total strangers. Faces and accents and tiny idiosyncrasies in people, gestures, body language, random bits of conversation that have absolutely nothing to do with me. And yes, of course, I overheard the conversation you reference above!

What were the challenges of using multiple voices, slang and patois in the novel?

I felt it a necessity, both artistically and technically. From a literary point of view, what I was really after was to celebrate Bakhtin’s idea of heteroglossia – which translates directly from Russian into “different speechness” or the variations in language within a single language. But even on the simplest level, if everyone sounded exactly the same, the book would be so lifeless and any attempt to reflect the complexity and diversity that makes London, London, would fall flat.

The challenge? Error, most definitely, error. I’ve been told I have a good ear, but at the end of the day, I am just me, I am not all these people, nor can I ever be. The best I can do is to listen and observe as honestly and with as much attention to detail as possible, but I’m pretty sure I’ve still made mistakes all over the place. But that kind of error doesn’t scare me. I view it as the price I have to pay for a genuine interest and curiosity about someone who is not me. That is the essence of fiction in my mind – to walk in someone else’s shoes, to inhabit someone else’s soul, albeit fleetingly. If I wanted to create some kind of perfect flawless thing, I’d have to limit myself to writing about me or versions of me, and honestly, I can’t think of anything more dull – can you?

I can’t write a single word until I feel I know my characters intimately. That gives me the trust to cede creative control to them and I more or less let them lead the narrative.”

Boundary Road is a real place, but also a gift of a title for a novel about borderline lives, and how even the most gentrified parts of London rub up against poverty and hardship. Did the title, the location or the characters come first?

For me, it’s always the characters that come first. Again, it sounds very prosaic, but I can’t write a single word until I feel I know my characters intimately. That gives me the trust to sort of cede creative control to them and I more or less let them lead the narrative. It’s not that I’m not present, but in a kind of close-third-person way if that makes sense. I’d always rather the reader hear the character’s voice than the authorial voice. So, when the climax of the story fell into place, the ‘when’ and the ‘how’ of it all, it was pretty obvious to me that the ‘where,’ had to be on that particular stretch of Boundary Road. After that, there was only one natural title, really. The actual physical Boundary Road of the book of course is extraordinary in its character, the history of its etymology, the subtle or perhaps not so subtle delineation between NW8 and NW6 and everything that signifies. But even if you don’t know it, as you say, there’s so much depth to the ‘boundary’ of Boundary Road, just what the word connotes is so vast, so full of meaning and nuance. A gift of a title, really!

As I happen to be a local, I couldn’t help but notice small shifts in the actual geography of the area, and choices you made in naming and not naming certain landmarks. Can you talk me through the decisions to substitute Elizabeth Road for Alexandra Road; renaming Grenfell Tower; yet giving a callout to Bruno’s Deli?

(And does Bruno himself yet know that the deli gets a mention?)

There’s no real significance behind the choice in fictionalising certain places and not others, except for the choice itself. As a writer, you spend a really long time with the book, and at least for me, I need to find ways to keep it enlivening, even just for myself. What you’ve observed is me trying to play with the reader, to dip in and out of fiction and reality, to be specific about a certain material geography but then scramble it up to see if the reader can make those connections, because that in itself is a kind of connection that I make with the reader. Unlike in drama or stand-up or music, the writer is not present in the moment of reception, so it’s my way of speaking to the reader, of saying – are you still with me? Did you see what I did there? A certain kind of reader will play along! At least that’s the hope!

(I don’t think Bruno knows, at least not from me, but let’s just say it was a little homage!)

Despite the immediate confines of the bus, it’s a very visual and visceral book that includes plenty of flashbacks and external action that I could certainly see playing out for film or TV. What would be the biggest challenges in tackling a screen adaptation?

Thank you. That’s very flattering. I guess so much of what makes a compelling book is in the writing itself, so to translate it successfully across to a purely visual medium, you’d have to try and capture the philosophical underlayer that runs parallel to the narrative. The spirit of the book, if you will. I think attempting to transpose the poetry of the language is risking whatever Gertrude Stein meant when she said: “There’s no there, there!”

What are the themes that connect all your fiction writing to date? And what sets David and Ameena, Almost and Boundary Road apart?

The aspiration, always, is to complicate consciousness; to move the reader both intellectually and aesthetically. I do literally mean move – make them laugh, make them cry, make them think… like you were there before you read my novel, and now somehow, you’re here. No matter how miniscule that shift, if there’s a shift, that’ll do.

Your second question… I would hope it’s craftsmanship. Language matters to me. Rhythm, musicality, balance, all matter to me. A beautiful sentence matters. In a world where our commonplace language has become so trite and so ugly, where there are character limits and ‘like’ and ‘love’ have lost all meaning, language is almost all that matters.

What are you writing next?

I’m working on a psychological thriller about a woman whose story is drip-fed to the reader in 19 sessions with her psychotherapist. There’s a seriously twisted twist in the end and when I told it to my husband, his response was “Boy, your mind is one scary place!” Which is really reassuring. Writing-wise that is. Also, it’s in the first person which I’ve never done before. It’s exciting. I mean I’ve written about two words, but still…

—

Ami Rao is an award-winning British-American writer who has lived and worked in Asia, Europe, North America and the Caribbean. She has a BA in English Literature from Ohio Wesleyan University and an MBA from Harvard. She is co-author of the memoir Centaur with jockey Declan Murphy, and the author of the novel David and Ameena and the novella Almost. She lived in North London for many years, taking the Number 13 bus for her daily commute. When she is not writing, Ami can be found reading, listening to classical music or dabbling in jazz. Boundary Road is published in paperback and eBook by Everything with Words.

Read more

amiraowrites.com

amiraowrites

@EveryWithWords

Author photo by Vanessa Berberian

Mark Reynolds is a freelance editor and writer, and a founding editor of Bookanista.

@bookanista

wearebookanista

bookanista.com/author/mark