A fresh start

by Anna Smaill

Dinah Glover arrived in Tokyo to take up residence in a block ambitiously named Maison du Parc. The building was surrounded by concrete and clad in more concrete, pink and stuccoed. It was long and squat, like the egg casing of a huge insect.

Dinah had come on a work visa sponsored by Saitama Denki University. The interview had been completed over Skype; the flights had been paid for. She was here to teach English to undergraduate engineering and science students.

Her predecessor, Phil, met her at the airport to show her the train system. It was easy once you got the hang of it; you didn’t need to speak Japanese at all. When they reached their final stop, she followed Phil through a shopping district and down a long residential road. The neighbourhood was suburban and had a threadbare, dusty quality. There were a few empty squares of wild, weedy grass with high wire fences. A poster on bulging damp particle board showed a couple standing outside a new home. The woman held an infant in her arms.

‘There was a typhoon last week,’ said Phil, ‘but you missed it.’ They were at the apartment block now. A gravel-covered pathway made the clattering noise of Dinah’s suitcase all at once very loud.

‘Nice place,’ said Phil. She couldn’t tell if he was being sarcastic. His accent was Canadian. ‘One of your suitcase wheels is broken.’

He was right. It had split into two neat rounds like an orange. Dinah lifted the suitcase into her arms like a wayward child and followed him up the stairs. They were narrow and rusting so that flakes of white paint dropped down through the steps to the ground below as they walked.

When they reached the right floor, the top one, the landing seemed very provisional and narrow and Phil very broad and stocky in his bad suit. The railing only reached his upper thigh.

Dinah walked inside past him, removing her shoes as she did. There was a kitchenette with a small fridge and small toaster oven. A small table in yellowish pine. A door on the left, and one on the right, presumably to the bathroom and toilet. There was a futon couch near the far wall, and that was the end of it. There were sliding glass doors along the back wall and a narrow balcony beyond them.

Phil made it across the apartment in three steps in his stockinged feet. He slid the door open, gestured.

‘There’s your park,’ he said, without a hint of irony.

She went out and looked down. It wasn’t a park. It was a square of gingery gravel. No grass; no green. A few old plane trees lined the periphery, and there was a strange concrete play area rising up out of the dust. Some park benches, all of which were empty.

She was glad when Phil left. He gave her the key and some paperwork.

‘Good luck at SDU,’ he said. Then she was alone.

It was not simply that the neighbourhood was quiet. It was more as if, by some mutual signal, everyone in it had up and left. The silence was like an indrawn breath. “

The door to the apartment was made of metal like a submarine door. It made a ridiculously loud clang into the silent air as she left. The noise echoed around the whole building. She looked up at the other windows. It was very silent.

Dinah walked, which was pleasant to do after the long flight, the train ride.

The neighbourhood’s other buildings were similar to her apartment block, in muted, washed-out colours – pink, blue, cream, grey. Upper balconies had bedding hanging over the rails, as if the façades were covered in patchwork.

She walked and walked. It was very quiet – nobody on the streets at all. Through the gaps in fences she saw paved courtyards, small domestic gardens with assorted pot plants.

It was not simply that the neighbourhood was quiet. It was more as if, by some mutual signal, everyone in it had up and left. The silence was like an indrawn breath. She realised that she was walking quietly, listening. After a few blocks she came across a bike leaning against a wall. In its basket was a brown paper bag emblazoned with the words ‘Mister Donut’. The bag was crisply folded and the bike’s tyres were still spinning.

She turned a corner and almost bowled headfirst into an elderly woman. ‘Sumimasen!’ Excuse me. It was one of her first Japanese phrases.

The woman was crouched over in a patch of grass next to the pavement. There was a black plastic supermarket bag on the grass in front of her, and she was wearing a floral housecoat and zip-up slipper boots. Using a metal spoon she was digging slowly in the grass verge. As Dinah watched, the woman extracted the dirt from her hole and piled it up in a neat heap. When she had removed enough dirt, she reached into the supermarket bag and took out a small seedling. The flower was a bright, almost electric, blue. For a second it seemed the only spot of bright colour in the whole street, possibly the whole neighbourhood.

Dinah watched. The woman nestled it down into the hole. She scooped carefully with her spoon, then she put back the earth that had been removed and eased it in around the plant’s shoulders with great care. Like tucking a child into bed. She didn’t look up at Dinah all the time she worked. When she had finished, the leftover soil and the spoon went back into the plastic bag. She left, slipping through a gap in the fence.

Dinah kept walking.

Dinah opened the can and took a long swig. It was grapefruit flavoured. Below that, thank god, was a clean, dry alcohol with no flavour. The bubbles stung her throat.”

The train tracks. Then more apartment blocks. All concrete stucco like her own. A small supermarket. A drycleaner, a hairdresser, a few convenience stores. Some cafés and restaurants that looked somehow domestic, as if they were really people’s homes that had one day been turned to this purpose.

She bought a tall can of either soft drink or alcohol from one of the convenience stores.

At last she had walked the full circumference of the neighbourhood and was back at her apartment block. The light was fading as she looked up at the windows. There were three floors above the ground floor. She counted nine apartments in all. Three on the bottom floor and two on each of the three floors above. All of the windows were dark, except her own, at the top. She touched the key in her pocket. It was true that she did not wish to go back up. Too quiet. The windows around her too dark and blind.

The next corner, then, and the park. There was a metal chain strung between two dark metal bollards, but there were gaps on either side, large enough for a person. The plane trees stood like gentle sentries.

Peering in she saw that the wide space of fine, biscuity gravel was larger than the view from her apartment balcony had suggested. It was completely empty. She took a leaf from each of the trees and stepped over the chain. ‘One of each kind,’ she said to nobody.

What was the story again? You picked the leaves for something. To prove you had been down into the underground world. Or did you collect the leaves so you could use them later? They would transform into silver or gold, if you brought them back up with you to the surface. There was something about being silent. You had to be silent. It shouldn’t be too difficult to be silent here.

There were benches along the edge of the park and she sat on the first. From this position she could study the odd playground structure. The main element was a large dome of concrete, which had metal rungs embedded in its sides. It looked a bit like the hump of a prehistoric beast that had died and gradually subsided into the bath of gravel. It had a slide at one end; not far away was a small swing set. It didn’t look very child-friendly but resembled a piece of modernist sculpture more than anything.

Dinah opened the can and took a long swig. It was grapefruit flavoured. Below that, thank god, was a clean, dry alcohol with no flavour. The bubbles stung her throat.

There was a grapefruit tree in the garden of the house she had grown up in. She recalled the way it had grown, right in the middle of the lawn, popping rudely out of the grass as if it had burst through in a single night. Her twin brother used to twist the grapefruit right off the tree and bite right through the skin and the horrible white pith so that the juice ran down his chin. That was the kind of person he was. They were her brother’s fruit; she didn’t even really like them. Something morose and sharp and rebarbative about the taste and the way their heavy oil hung around. She smelt it now, the sourness and sweetness. It asked you to go back to your body in some way, like plunging into very cold water.

Dinah sat on the park bench and took another sip. She felt the mercy of mild drunkenness. She finished the tall can and placed it carefully next to her on the bench. Then she turned her attention to what was in her hand. She inspected the leaves. They were large and palmate, a late-spring green. There was writing on the back, scribbles from an insect that had recorded its journey. She studied the message for a long time. It was in a different language to her own. She had known it once, but now its meaning was lost altogether.

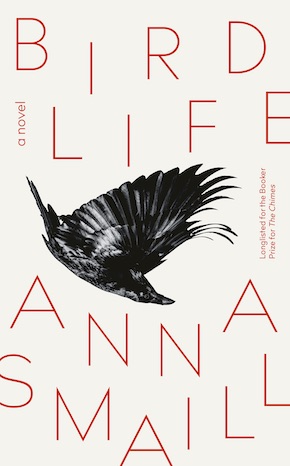

from Bird Life (Scribe, £16.99)

—

Anna Smaill is a poet and novelist. She was born in Auckland, and lived in Tokyo for two years before moving to the UK where she completed a PhD at University College London. In 2015, she published her debut novel The Chimes, which won the World Fantasy Award and was longlisted for the Booker Prize. She lives on Wellington’s south coast with her husband and their two children. Bird Life is published by Scribe in hardback and eBook.

Read more

annasmaill.com

@AnnaESmaill

@ScribeUKbooks

Author photo by Ebony Lamb

“Magic, mental illness, and sorrow drive this powerful offering. Smaill excels equally at emotional drama, magical realism and horror. Readers will find much to love.” Publishers Weekly