Atoms like snowflakes

by Carlota Gurt

“The best of short form writing from across the world.” The Manchester Review

We are in a city where all the streets go up and down, urbanism on an inclined plane, the goddamned omnipresent sea or mountains, sea to the south, mountains to the north, and a scar in the form of an avenue that bisects the city on the diagonal – skewed along a physical, moral, class angle that is its scourge – and the hills that try helplessly to constrain it so it doesn’t overflow in all directions. We are in an uncontainable city.

Yes, Senyora P. lives in Barcelona, and right now she is walking up a street – a torrent, as they call it, in this case a torrent of flowers, à la Rodoreda. But there are no longer any fragrant camellias or wisteria to be seen, now it’s all rows of motorcycles and the pestilent hydrography painted on the pavement by dog piss. She is sweating unbearably, not just because of the Via Crucis of the steep incline, but also because she is dragging her shopping cart behind her, from which a bulky rectangular package sticks out two hands high, containing a device which, despite its laughable weight of a mere three kilos and 300 grams, is capable of executing a thorny task, surely the thorniest task there is, a task which no human being wishes to carry out.

The clerk had offered her free home delivery but that would have meant waiting until the next day, and Senyora P. has had enough. She has been saving up, and dreaming and, above all, waiting, for ten years.

She drags the shopping cart up the last few metres to the door. Huffing and puffing, she crosses the vestibule and casts one more glance at the lair of the concierge, which has stood empty for decades. In this new century, concierges are relics only lavished on the posh menagerie of the Upper Diagonal.

She likes living on the ground floor, at street level. It seems less ambitious and more human to her than being caged in a sixth-floor apartment with too much light to stay grounded. In the foyer, she catches a glimpse of herself in the mirror. Marymotherofgod, if she doesn’t look like a crazy old woman, in her housecoat, with a mop of white hair rebelling like a raging storm at sea. She needs to go to the hairdresser’s, but since her lifelong salon went out of business, the time has never seemed right to try one of those spectacular modern establishments, nor does she have any reason to. To be honest, why would she?

She takes the unwieldy package out of the cart and unwraps it impatiently. Ten years of waiting and now, finally, the eraser is on the table.”

A rather unsubtle moustache marks her upper lip which, in turn, shrinks back inside her mouth, leaving no doubt that today, yet again, she is not wearing her teeth. Lately, she just doesn’t put them in, she doesn’t see the point and, what’s more, she’s a bit afraid she’ll glue them in with the denture adhesive and never be able to take them out again. Sometimes she even dreams about it. She sees Senyor P. approaching her with a hammer and chisel to yank the fake smile out of her gums. Maybe, in fact, this is the thing: she has never tolerated dishonesty or trying to gussy up ugliness. That must be why she lives in this city, though we could certainly find someone who would say exactly the opposite.

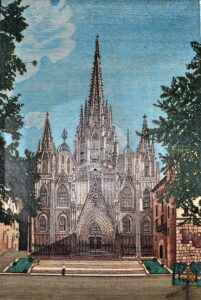

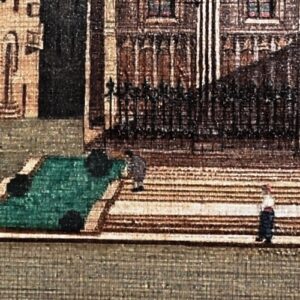

Detail from Barcelona Cathedral by Montserrat Alberich Escardívol (1912–1973), created using a typewriter. Barcelona City History Museum (MUHBA)/Wikimedia Commons

Once in the living room, she doesn’t stop to rest for so much as a minute. She takes the unwieldy package out of the cart and unwraps it impatiently. Ten years of waiting and now, finally, the eraser is on the table. Luckily, she still has a head for technological things. Once she’s read the short manual, she plugs in the machine and the main funnel begins to emit a relaxing buzz.

She places the pinky toe of her left foot inside it and feels a delightful tingling, a melodic wave that flows over her skin. At the other end of the funnel, a little cloud is coming out that soon dissolves into the air: her invaluable contribution to the most polluted air in Europe.

The shopkeeper was right, it didn’t hurt a bit. That was the only thing that had given her pause, the pain. Well, the pain and the blood, but there isn’t so much as a drop. Once she has carried out the deatomisation test, she pulls her foot back, sans small toe, and sticks the exhaust duct out the window. Everything’s ready.

Before starting the procedure, she goes to the kitchen, picks up two bars of dark chocolate and leans on the windowsill to contemplate the bustle of the city for the last time. She lets the chocolate melt in her mouth. It’s delivery time: vans with four blinking lights and drivers quick to honk. The walls, like everything else, are obliterated under the young people’s uninspired graffiti, as if by plastering a twisted signature there they were taking possession of something. They, the dispossessed, it’s the only way for them to own anything. But today Senyora P. is not grumbling, she even looks at the tags with magnanimity and is amused to think that, before she goes, she too might leave her signature on the façade of the building where she has spent her entire life, a good life.

The indifference on the faces of the passersby surprises her. It’s out of sync with the joy she is feeling. She wished everyone was singing and dancing as if in a musical, and passing trucks were tossing out candy, and everyone was having canelons for lunch. Her day of liberation is here.

But no. Ever since some scoundrel put canelons in a different kind of eraser nurtured over decades that also turns everything into smoke, the cannelloni brought here by fin-de-siècle Italian chefs have lost all interest; old-fashioned cooking is out of fashion.

She leaves the window half-open and ensconces herself on the sofa with the still-buzzing machine in front of her. The instructions make it clear that you must proceed from the feet to the head so as not to leave the job half-done.

She sticks her whole left foot inside, all at once, ignoring the explicit warning to proceed bit by bit to avert obstructions. The eraser lets out a howl and Senyora P. fears the worst, but the contraption starts to deatomise her foot. She feels her molecules being decomposed with a caress.

Her foot is erased, but not the memory of when she broke it a year ago and her son had to come and live with her for a few weeks. Manel. Poor Manel, he’s not going to understand. Is it so hard to see that she’s done all she’s going to do? That she has no reason to keep getting up in the morning?

Manel insists that she’s depressed. He doesn’t get it. Even as a kid he was a little peculiar, in his own world, playing with his strings and gadgets. He’s not a bad kid, but he lives in his own bubble. He always takes her by the hand, imitating gestures he’s seen. He can’t find his own way to express what he’s feeling. Or maybe he doesn’t feel anything. Manel and feelings, a fish on a bicycle.

She sticks her whole leg into the funnel, little by little now, so as not to overwhelm the machine. When the tickling is almost at her groin the phone rings. Damn, she forgot to disconnect it. She tries to ignore it. It rings ten times and stops. Finally. But it starts up again right away.

She gets up, a little aggravated, balancing on the foot she still has and holding on to the shelves full of books from fifty years ago that no one has ever read. Her knee creaks, the office door creaks, the city of last century also creaks under the pressure of the new city pulverising it. She makes her way down the hall to the telephone, which is now ringing for the third time.

‘Yes? Manel, I can’t talk now. No, you don’t need to come over, I have things to do. What things? Things I want to do, son, that’s all. But take care. You know I won’t be around much longer. No, I’m fine, just fine. Big kiss. I love you. No, don’t be stubborn, there’s nothing wrong, can’t I even say I love you? Yes, okay, talk later.’

She unplugs the phone and the creaking starts again, the creaking that precedes the final collapse.

Love, the antithesis of the eraser: a machine that creates matter where there was none. Without her even realising it, the funnel has sucked up her belly button.”

When she gets back to the sofa, she’s exhausted from the expedition. She’d better get a move on. It’s time for the right leg. She resists the temptation to stick it in all at once and get it over with, and decides to enjoy the pleasure of the moment. That’s it, no more walking, no more varicose veins – those blue worms that tunnel down her legs – no more cramps, no more torture of climbing stairs. Outside, the exhaust tube excretes a thick cloud of smoke.

The eraser starts to make a blur of her pubis and for a moment, like a sleeping beauty after a hundred years of lethargy, her strawberry wakes up – that’s what Senyor P. used to call it when he played with it – and all those nights of naughty secrets with her husband rush into her head, and the moment when he lost his drive, and she wasn’t in the mood anymore and they would just cuddle tenderly, more out of habit than love. Or maybe not, maybe that’s exactly what love is, she doesn’t know anymore. She surrenders to thinking about the nature of love and remembering that immense and fleeting sensation. Love, the antithesis of the eraser: a machine that creates matter where there was none. Without her even realising it, the funnel has sucked up her belly button.

Outside she hears two women’s voices talking about incomprehensible things in that hellish language that’s spreading through every neighbourhood like a plague. She’s doing the right thing to leave now, just in time, before the city becomes entirely unintelligible to her, leaving now, happy and in full possession of her faculties, cushioned by the sweet memories of the seven-and-a-half decades that she has been beating this asphalt. When you’re playing cards, you also have to know how to stand with a seven-and-a-half to win.

Now she wonders if she should lift her arms and leave them for the end or stick them into the machine. She doesn’t have enough stomach muscles left to get up and consult the manual or stop the eraser and think about it for a while. Zumzum. Time to decide. Tick-tock.

With the wisdom of Solomon, she decides to stick one arm in and leave the other for the end. Her right hand sinks into the funnel. Goodbye pain in her joints every time she opens a can of tuna, opens the blinds, closes the gas valve. Goodbye writing with a shaky pulse. Goodbye holding Manel’s limp hand, always sweaty and ridiculously fearful, having to sense his attempts at tenderness.

What a relief!

The contraption moves up past her withered nipples and swallows the parchment skin of her breasts, the same breasts she used to parade through the streets of Gràcia during the Festa Major, the August street festival that has morphed into an absurd mess of beer, tourists, and gigantic amplifiers; the same breasts that in her youth coveted a full life and discovered the enigmas of maternity; the breasts that fed Manel when he was born, which as a baby he had already suckled with the same scant desire with which he now imbibed life.

The atoms of her heart are already dissolving out through the exhaust pipe, and Senyora P. feels a comforting inner silence. Enough boom-boom. Infinite serenity. She wishes she could thrust herself in so the eraser could swallow her up in one gulp, but she restrains herself. Now all that is left is her head and her left arm, which is resting on her nest of hair.

She feels the turbulent massage of the extractor at her chin and, before it’s too late, she decides to hear her own voice for the last time and shouts the first thing that comes into her head, not trying to say anything brilliant, because she doesn’t have time to think. She just bursts out with all her lung power, I’m on my waaay, but she hasn’t even got so far as the ‘y’ when the eraser silences her on its determined way to her nose and ears.

She looks at the ceiling and the light fixture that Senyor P. bought too many years ago in that store that doesn’t exist anymore. Remembering this, the liberating joy she feels is tinged with an old sadness.”

Senyora P. isn’t focusing on odours – she hasn’t smelled anything in years – but on sounds. She hears her upstairs neighbour beating an egg, a truck wheezing to reach the top of the hill, the back and forth of a pair of high heels punishing the sidewalk and, in the background, the hypnotic buzz of the eraser. Suddenly, total silence with the density of lava, which is a little intimidating and, more than anything, out of character for this uncontainable city, always screeching like a starving newborn.

Her eyes open wide as she notices the tickling at her cheeks. She looks at the ceiling and the light fixture that Senyor P. bought too many years ago in that store that doesn’t exist anymore. Remembering this, the liberating joy she feels is tinged with an old sadness. Her eyes become moist and there is still enough time for them to squeeze out one last tear which, like her tired pupils, soon turns to atoms.

The funnel chews up her parietal and frontal lobes, and she is assaulted by an uncontrolled army of memories bubbling up amid disconnected sensations. Her memory is dissolving like an effervescent tablet. Fragile, ephemeral bubbles. Memory in eruption.

The taste of horseradish as the breeze ran through her hair on the green tricycle. The warm smell of madeleines as she felt Senyor P.’s hands on her waist. A velvety sensation and her mother’s fava beans à la catalana. A strange iron aftertaste as she sees herself walking down the Portal de l’Àngel holding Manel by the hand. The acidic impression of her first French class with Mlle Thibaut in that neighbourhood of houses clustered on the hill, leery of the city at their feet. A restful hum as she watched her father loading sacks of flour. A spongy warmth as Manel recited the Christmas poem like an automaton. The salty vertigo of the night she lost her virginity. The strident bitterness of the day she cut herself on the knife for carving ham off the bone. The rough sketches she traced with her footsteps on the Barcelona of yore, now dead. The fossilised memories pile up without allowing her time to react, and soon the eraser vacuums up her language and she can no longer sensibly articulate ideas.

Everything turns into sensation, thought in its pure state.

Without hearing or sight, she can’t perceive how close her son is, how a few seconds ago he turned the southern corner and, seeing the thick smoke pouring from the ground-floor window, started running at full speed.

He stops in surprise when he reaches the smoke, as it doesn’t smell of burning. He sniffs it with a scientific curiosity and breathes in a few very tiny air bubbles that make him sneeze. For a moment he feels a mass of sensations: a strident bitterness, a spongy warmth, a salty vertigo and, above all, a total freedom, a science fiction plenitude. He dispels these indecipherable emotions, pulling the curtains aside in one fell swoop and watching his mother’s last hairs disappearing into the funnel. He jumps over the window bar and rushes to turn off the machine.

He gets there just in time to avert her complete volatilisation. Her left hand, which had been resting on her head, has been salvaged. He will keep it in a fishbowl full of formaldehyde at 36.5 degrees Celsius. Every morning he will hold that warm piece of dead flesh just as he has always done, and with the obstinacy of a man who can’t tolerate things moving forward, changing and dying, he will persist in not understanding why his mother wanted to disappear.

To no avail, though, because the rest of Senyora P. is drifting freely down the street, like a liberating torrent of atoms sneaking into all kinds of noses, invading Greek and Roman protuberances, climbing clandestinely into nasal cavities like an invisible neurotoxin, a chemical weapon insisting on spreading happiness amid all the urban din. Her molecules are now inseparable from those of the conquered organisms, irreversibly amalgamated with them.

Maybe this, too, is the city, the promiscuity of atoms that fall lightly onto the asphalt like flakes of snow, burying the times and the ruins of past lives.

This evening, in ancient Barcino, where all the streets go up and down, someone will eat a plate of canelons with delight.

Translated by Mary Ann Newman. From the anthology The Book of Barcelona (Comma Press, £9.99)

This story was first published in Catalan in Cavalcarem tota la nit (‘We Will Ride All Night’, Proa, 2019)

Carlota Gurt is a writer and translator. She has translated work by Nino Haratischwili, Hans Magnus Enzensberger, Peter Handke, Sarah Lark, and David Safier, and was previously production manager for La Fura dels Baus and the Temporada Alta Festival. Her first collection of short stories, Cavalcarem tota la nit won the Mercè Rodoreda Prize.

Carlota Gurt is a writer and translator. She has translated work by Nino Haratischwili, Hans Magnus Enzensberger, Peter Handke, Sarah Lark, and David Safier, and was previously production manager for La Fura dels Baus and the Temporada Alta Festival. Her first collection of short stories, Cavalcarem tota la nit won the Mercè Rodoreda Prize.

@CarlotaGurt

instagram.com/la_gurt

Author portrait © Sergi Alcazar

Mary Ann Newman translates from Catalan and Spanish. She has published a collection of short stories and a novel by Quim Monzó, essays by Xavier Rubert de Ventós and poetry by Josep Carner. Her most recent translation is Private Life, a 1932 Catalan classic by Josep Maria de Sagarra. She is President of the Jury of the Premi Internacional Catalunya, a member of the PEN America Translation Committee, and director and curator of the Sant Jordi NYC Book Festival.

@newm161

The Book of Barcelona, the latest anthology in the acclaimed ‘Reading the City’ series, edited by Manel Ollé and Zoë Turner, is published in paperback and eBook by Comma Press.

Read more

@CommaPress