Before my story had a hero, it had a villain

by Jack Anderson

My debut novel, The Grief Doctor, follows Arthur Mason, a man consumed by the recent loss of his wife Julia. In the pit of his desperation, a lifeline descends in the form of Dr Elizabeth Codelle, a visionary psychiatrist with a private practice off the North Wales coast. Seeking an end to his turmoil, Arthur submits himself to Codelle’s care, but quickly becomes a prisoner to her radical views on grief.

The story itself clings tight to Arthur’s perspective, as he fights to understand and ultimately escape the strange corridors of Prismall House. However, the conception of this story didn’t start with its hero. It started with Dr Elizabeth Codelle, the story’s principal antagonist (though, of course, she doesn’t see it that way).

About two years ago, a question struck me, seemingly out of the blue: what would grief look like if it were viewed dispassionately, without the romanticism or humanity we attach to it. Would it seem like an affliction? Could it be argued that it serves more harm than good?

The idea was a little disturbing, a little darkly fascinating. I wondered about those who are debilitated by a bereavement, who suffer from prolonged grief that threatens their day-to-day function; to what degree would it be ethical to intervene? Would it ever be right to hijack such a personal process if it means returning someone to function? A voice in my head, that wasn’t entirely mine, insisted, “It would be unethical not to.”

Whether I agreed with this viewpoint or not, I found it increasingly compelling to engage with this perspective. Right or wrong, it seemed able to defend itself, meeting my romanticism about grief and loss with a far less sentimental, but equally compassionate response. Soon enough, this strange point of view developed a voice, and that voice took on a name: Dr Elizabeth Codelle. As soon as she arrived, I knew I had a fascinating opportunity. A chance to engage with my favourite type of villain.

There are countless archetypes for a ‘villain’, all of them valid in their own nasty ways. Some antagonists, like Hannibal Lecter or Sauron, are an almost elemental, self-professed evil. Though undoubtedly complex, they evoke a sense of old school, fairy tale monstrosity.

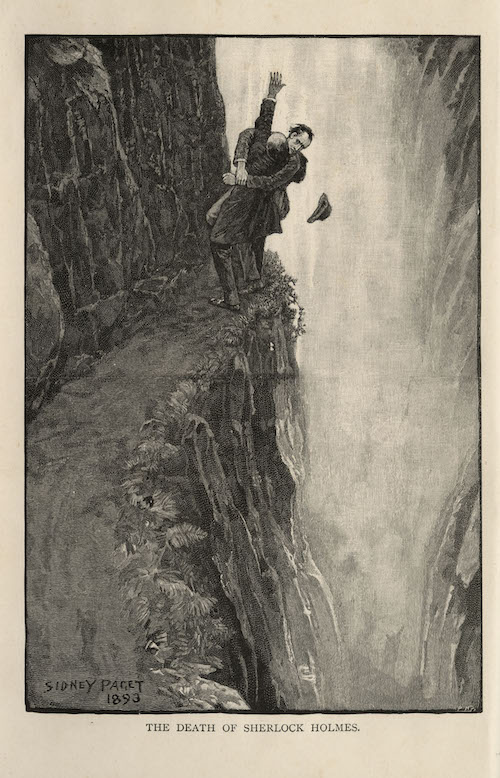

Others, your Moriarty, Tom Ripley types, subscribe to a more banal creed of selfishness and ambition. They can be practically superhuman, but their flaws are the same you encounter in all human beings; greed, apathy, jealousy, pettiness and wrath.

But there is a somewhat rarer subset of antagonist, a villain whose north star is not malice or self-interest, but a profound and unwavering philosophy that they hold to incorruptibly. If the protagonist agreed with them, they would become an ally. If the world agreed with them, they might be the protagonist. Unfortunately, almost tragically, the beliefs they hold so strongly are simply incompatible with the world at large.

Sherlock Holmes gains the upper hand because he’s willing to risk what a self-interested person cannot. He is willing to die for his principles, where Moriarty simply can’t take that leap.”

Victor Hugo’s Javert in Les Misérables is a prime example of this archetype. He possesses no passion for evil, he is incorruptible by greed or self-interest. His ultimate belief in the rule of law drives him ceaselessly and unselfishly. He is almost an optimist, believing if everyone followed the rules, then there would be a place for everyone in society.

A more contemporary, but equally valid, example might be Magneto of X-Men fame. The young Erik Lehnsherr survived systematic oppression and extermination and years later, as Magneto, sees that same oppression on the horizon against his people. Of course, an unsettling question looms over his character: how forcefully, how pre-emptively, can you push back against your would-be oppressors before you become a tyrant in your own right? However, there’s no question that Erik Lehnsherr believes in what he’s doing and that he would do anything to uphold his principles.

In writing Dr Codelle, I came up with an interesting litmus test to help identify a member of the principled villain archetype. At least I found it interesting. In broad strokes, there is a difference in resolve that separates heroes and villains, that allows the former to usually win the day. While it is perhaps a little simple, I characterised it thus: Heroes are willing to die for what they believe. Villains, at most, are only willing to kill for it.

In many cases, this deficit in resolve can be felt within a story. When the chips are down, the hero is simply willing to risk more, accept more danger than the villain. Moriarty could not conceive of throwing himself into the Reichenbach Falls. Sherlock Holmes gains the upper hand because he’s willing to risk what a self-interested person cannot. He is willing to die for his principles, where Moriarty simply can’t take that leap.

A principled antagonist bridges that gap, standing on a level playing field with the hero. It’s fascinating to read, and fascinating to write. At a fundamental level, we’re seeing two protagonists face each other, with terminally incompatible views and no way to resolve them other than conflict.

When you have two protagonists in conflict, the rules begin to bend, and it becomes very difficult to tell who might win. That’s what excited me about creating Dr Elizabeth Codelle. It’s been a privilege to engage with this fascinating species of antagonist, to write a character whose arguments I feel I could adequately represent in a debate, someone who believes so strongly that they’re right, and whose darkest actions are driven by a true desire to do good on her own terms. I’ve even had people read this story who ended up sympathetic for Codelle and her perspective. I’d be lying if I said I expected it, but it’s a fascinating thing to hear.

I can only hope, when the novel is read by the world at large, it will at least prompt some interesting discussion. Discussion of this strange character, the unorthodox values that she holds so dearly, and where she went wrong and, fascinatingly, where she may be right…

—

Jack Anderson is the author of the viral internet serial ‘Has Anyone Heard of The Left/Right Game?’ which has since been adapted into a hit QCode podcast. He lives with his wife in Sheffield. The Grief Doctor is published by Raven Books in hardback, eBook and audio download.

Read more

jackandersonwriting.com

@neon_tempo

@BloomsburyRaven