Blood well shed

by Brett MarieEarly in his debut crime novel Clinch, Martin Holmén makes a play at our sympathy. Waiting for a business contact in the streets of 1930s Stockholm late one autumn evening, former boxer Harry Kvist spots a man beating a stray dog across the way. Kvist is quick to call the man out on his cruelty, allowing the dog to escape (“There’s really no reason to beat a dog half to death like that,” he tells us in an aside). I’m guessing that Holmén has read screenwriter Blake Snyder’s screenwriting bible Save the Cat! The Last Book on Screenwriting You’ll Ever Need – coming to the rescue of a defenceless animal is precisely the act Snyder prescribes for persuading an audience to root for a protagonist from the get-go.

But if the author is willing to make a stab at likeability, it’s clear his heart isn’t quite in it: minutes after the dog has scurried off into the night (nearly getting hit by a car in the process), Kvist gets down to business, namely the violent shakedown of his contact, a car buyer who has stiffed his seller for a couple of thousand kronor. By chapter’s end, Kvist has assaulted another victim, this one a young man whom, after picking him up for sex on a car dashboard in a secluded park, he nearly kills with a single punch to the jaw – delivered because Kvist doesn’t like the young man’s lisp. Our ‘hero’ will give a scratch or a morsel of fish to a cat here and there going forward, but he dispenses far more brutality on the story’s two-legged cast – and it will be another hundred pages before the guy musters an act of genuine decency toward another human being.

There’s not much to like about Harry Kvist – but then Holmén needn’t worry about a charisma gap. Yes, readers need to root for a hero to become invested in a story. But who needs phony virtue, with the card Holmén has up his sleeve? Two chapters on, Kvist gets a visit from two ‘goons’ (Kvist’s entirely unironic term for policemen). After a brief scuffle, the goons overpower him, slap cuffs on him and bring him in for questioning. Kvist’s first assault victim has since been murdered, and the authorities seem pretty certain they have their man. The goons soon release Kvist with a warning that they’re onto him. Thus is revealed the tried-and-true plot of the innocent man, wrongfully accused.

It doesn’t matter how many wrongs I see a character commit; if I see him getting railroaded for something he didn’t do, I’m in his corner. For some strange reason, the minute the finger is on Kvist, I’m behind him.”

We’ve seen this before: a man framed for a murder he didn’t commit spends the length of a story striving to keep one step ahead of the authorities, while at the same time desperately trying to find the real killer before the clock runs down. It was a favourite theme for Hitchcock (see The 39 Steps), and enough people rooted for the principled Dr Richard Kimble in the sixties TV series The Fugitive to justify an exhilarating blockbuster reboot thirty years later. Of course, Harry Kvist is no Richard Kimble. But I learned something about myself as I read Clinch, something interesting about my moral sense: it doesn’t matter how many wrongs I see a character commit; if I see him getting railroaded for something he didn’t do, I’m in his corner. Perhaps it’s not the man I’m getting behind, but rather the concept of justice. Case in point: my modern sensibilities are rankled when the authorities reveal Kvist’s past convictions for homosexual acts, and try to use those convictions to paint him as a villain. So rankled am I, in fact, that his truly villainous deeds suddenly take a backseat in my mind. For some strange reason, the minute the finger is on Kvist, I’m behind him.

My righteousness is far from consistent going forward. It speaks well of Holmén’s writing that I suspend my morality along with my disbelief for the length of the novel. As Kvist scours Stockholm’s underworld for clues to the murder, he opts for the stick as often as the carrot to coax information from the people he meets. It often seems that for every new face he encounters, Kvist requires a pint or so of blood to seal his acquaintance. And although I consider myself a man of peace, I find myself willing to allow this wanton savagery, if it’s deployed in the pursuit of clearing Kvist’s name. When a mob ally grabs two small-time gangsters on our hero’s behalf and finishes his interrogation of them with a series of gunshots to the head, my horror lasts for only the single sentence Kvist takes to consider the fates of the poor thugs’ families. Like Kvist, I leave all guilt behind with the bodies.

Come to think of it, Kvist’s brutishness is more than just something to overlook. In a thriller which leans more heavily on fight than flight, I’m actually thankful for the boxing scars that crisscross his face, for his mangled pinkie finger, for his callous personality. The beatings he takes, like the recurring cough brought on by his constant cigar-chomping, are easier to absorb as a natural side-effect of his lifestyle. Drawing blood from Robert Donat or Harrison Ford is like dinging the door on a pristine Bentley. By contrast, Kvist is a banged-up old Volvo; the bad guys heap punishment on him throughout the book, but each wound is just one more dent.

One thing that does shock is the state of Stockholm in the thirties. Far from the social-democratic ShangriLa that I’ve visited, Kvist’s Stockholm is a maze of filthy streets, populated by an unwashed mob of street urchins, gangsters and prostitutes. Parks are reserved for sex and murder, factories spew out armies of beaten-down labourers at closing time, and across the city, at all hours of the day, the bells of a dozen churches toll eerily, as if in judgment. A relationship with a former movie star eventually brings Kvist out of the slums and into Stockholm’s more glamorous locales, but the pervasive poverty of the book’s place and time is never far out of the frame. And here is where Holmén’s gift for evocative similes, in the Chandler tradition, lifts the book from the gritty doldrums of the crime genre. For Holmén, a moonlit Salvation Army soup line is a linguistic opportunity: “The line of sick, silent faces shines palely like a pearl necklace dropped in the gutter.” Flourishes like this, translated into a surprisingly mellifluous English by Henning Koch, are in line with Kvist’s taste for dapper suits and devotion to the Social-Demokraten crossword puzzle. Together, these elements add the thinnest veneer of class to the story, glossing over the grime and bloodstains just enough to make them palatable.

Periodically I must close the book and remind myself that Clinch‘s fantastically atmospheric setting depicts the real, heartbreaking suffering of the Great Depression, that the action scenes I’m eating up are actually grisly crimes perpetrated by cold-blooded criminals. That Holmén manages to sneak his story past my keen moral-outrage sensors is a testament to a fine writing talent. Harry Kvist is in many ways a monster — Rocky Balboa he ain’t. But with all that he has to go through to clear himself of the one awful crime he doesn’t commit, he has at least one squeamish, peace-loving reader with him to the last page, cheering with every punch he lands.

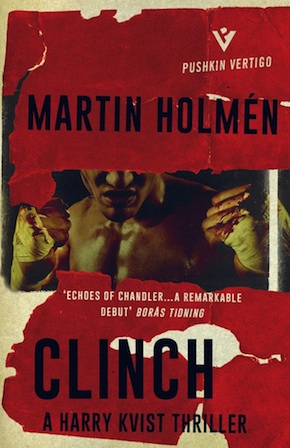

Martin Holmén was born in 1974, studied History at university and now teaches at a Stockholm secondary school. Clinch, his debut novel and the first installment in the Harry Kvist trilogy, is published by Pushkin Vertigo. Read more.

Martin Holmén was born in 1974, studied History at university and now teaches at a Stockholm secondary school. Clinch, his debut novel and the first installment in the Harry Kvist trilogy, is published by Pushkin Vertigo. Read more.

martinholmen.se

Brett Marie, also known as Mat Treiber, grew up in Montreal with an American father and a British mother and currently lives in Herefordshire. His short stories such as ‘Sex Education’, ‘The Squeegee Man’ and ‘Black Dress’ and other works have appeared in publications including The New Plains Review, The Impressment Gang and Bookanista, where he is a contributing editor. He recently completed his first novel The Upsetter Blog.

Facebook: Brett Marie

@brettmarie1979