Blood, Bible, Brer Rabbit and The Bear

by Lisa HoworthIn my neck of the woods, so to speak – the southern United States – the question is often posed, especially by people who are from away: “Why is there such a rich literary tradition in a region known to most of the world (those who know it at all) as poor, and religiously and politically conservative?”

The infamous American journalist and contrarian, H.L. Mencken, maybe known to Europeans as something of a German-friendly World War I correspondent, or for a scathing piece he wrote called ‘The Anglo-Saxons’ (UK friends, check it out), once dubbed the South “almost as sterile artistically, intellectually, culturally, as the Sahara desert”. But this was in 1917, before William Faulkner, before Thomas Wolfe wrote Look Homeward, Angel, Margaret Mitchell wrote Gone With The Wind, Zora Neale Hurston wrote Their Eyes Were Watching God, or Tennessee Williams wrote plays. Before Richard Wright wrote his grim chronicle of African–American life, Native Son, James Agee wrote A Death in the Family, and Eudora Welty, Carson McCullers and Flannery O’Connor published their wonderful stories. (At about this point, Mencken took credit for goading southern writers off their asses and creating a literary renaissance). And then there was James Dickey penning his compelling poetry, the existential novelist Walker Percy, Harper Lee with To Kill a Mockingbird, William Styron’s stunning novel Sophie’s Choice, and the early work of east Tennessean Cormac McCarthy. Faulkner was acclaimed by the 1930s, and Mencken began publishing his short stories in the American Mercury, of which he was editor, and he requested a photo and bio from Faulkner’s agent. Faulkner, whose memory was long and disposition feisty, sent this mocking reply: “Sorry, I haven’t got a picture. I don’t intend to have one that I know of, either. About the biography. Don’t tell the bastards anything. It can’t matter to them. Tell them I was born of an alligator and a nigger slave at the Geneva Conference… Or whatever you want to tell them.” (Fortunately the agent did not relay the message.) But it wasn’t until 1950, when Faulkner received that ultimate literary trophy, the Nobel Prize, that he was widely regarded as one of the greatest voices in the English language, right up there with Shakespeare and Joyce, some say. Perhaps this was when that question was first raised: WTF is it about the South that foments so much great literature?

The American South is a place where dramatic history, vastly different cultures, and an extraordinary environment create a world that is irresistible to writers and has fascinated readers since the 16th century.”

Faulkner hailed from Mississippi – the ‘most southern’ of the southern states – the poorest and most backward state of all. So did Wright, Tennessee Williams, Welty, Richard Ford, Donna Tartt, Barry Hannah, Larry Brown – authors known internationally. One might ask the smaller question: Why Mississippi? Getting even more specific, if you looked on Google Maps for Yoknapatawpha County, Faulkner’s fictional “little postage stamp of native soil” where he lived and centered most of his novels and stories, you’d find that little red balloon thingy would drop on Oxford, Mississippi, (the other Oxford) population 20,000, where I live, and where a disproportionate number of well-known writers like Hannah, Brown, Willie Morris and John Grisham have called the town home. Novelist Pat Conroy (The Prince of Tides) called Oxford “the Vatican City of southern letters”. So what’s up with the little backcountry town? More about that later.

Negro Life at the South, oil on canvas, 1859, by Eastman Johnson. New York Historical Society/Wikimedia Commons

The answer to the bigger question is both easy and complicated. The short answer is a little duh… The American South is a place where dramatic history, vastly different cultures, and an extraordinary environment create a world that is irresistible to writers and has fascinated readers since the 16th century when the first European explorers and naturalists began describing it. The longer, more complex answer, an elaboration on the above, is to look more closely at the origins of southern people, their histories, and at the wild diversity of the natural world in the South.

Where there were three very different cultures coming together – Native American, European, African (and more recently others) – so intimately but unnaturally entwined, there will be passion, conflict, tragedy, and a desperate need for expression and communication. The most obvious example would be musical – the field hollers, spirituals and blues music that grew out of the slave experience, when only non-literate forms of expression were acceptable to white masters. The remarkable music of African-Americans was vital – often harking back to the music of the African societies from which slaves had come. Where would the world be without the haunting, blood-stirring, blues songs that evolved into jazz and rock ’n’ roll? No Elvis, no Stones, no Louis Armstrong? No Black Keys? I choose to include blues masters like Muddy Waters, (who literally electrified American music) Robert Johnson or Bessie Smith in the South’s literary heritage, as well as the great folk musicians of the southern mountains like the Carter Family, the father of bluegrass Bill Monroe or Florence Reese, composer of the coal mining protest song, ‘Which Side are You On?’ Although some of their music was traditional with English, Welsh, or Scots-Irish origins, imagine: no Lonnie Donegan or Billy Bragg?

The South has been a battleground – a land of vicious bloodshed, rebellion and resistance – for centuries, and some might say it still is. All its people have been ‘invaded’ by governments – people with causes – just or not. Everyone suffered here; some more than others to be sure, but all southerners have felt oppressed at some point in history. I don’t just refer to colonialism and the American Revolution, much of it fought and ended here (no hard feelings!) and the Civil War, which sometimes pitted brother against brother, but to fights against indigenous people and the Trail of Tears which forced Native Americans westward from their southern lands, and to the many tumultuous years of the civil rights struggle. Everyone in the South experienced defeat, impoverishment, humiliation and feeling ripped-off, even if they deserved to be. White southerners have felt a huge compulsion to explain their misguided, inhuman lost causes and their abiding, deep love for the South, despite its awful past, as Faulkner has his character Quentin Compson do in Absalom, Absalom when his Canadian roommate at Harvard begs him to “Tell about the South.” A critic, Fred Hobson, has called this compulsion a “rage to explain”, believing it’s common to all southern writers, whatever their color.

Battle stories, stories of rising above oppression, stories of survival against all odds, make great dramatic literature, oral or written. The famous civil rights anthem, ‘We Shall Overcome’, and Scarlett O’Hara, the prototypical belle in Gone With the Wind, vowing as she roots for turnips after the Yankees loot and destroy Tara, “As God is my witness, I’ll never be hungry again” come to mind. In the South there has never been a dearth of subject matter to sing or write about, for sure. In this, a rich historical background fueling an immense, vibrant storytelling tradition, I see the South as very like Ireland and Russia, other places that have experienced defeat, oppression and violence and from it created a brilliant literature. There are the characters struggling to survive, or just to exist not unhappily, failing or not failing, and often created by authors with dark, gallows humor; a tool to go on. I think of Flannery O’Connor, Solzhenitsyn, the samizdat writer Venedikt Erofeev, Lyudmila Ulitskaya, William Trevor and Patrick McCabe as modern examples. In Native American and African-American culture storytelling was essential too. Stories were the way family and community history was passed down, and stories instructed younger generations. Out of handed-down tales, Alex Haley and Alice Walker have written about what southern history meant to their people. There were humorous trickster stories, like the creolized ‘Uncle Remus Stories’ of slavery days in which the trickster Rabbit, common in Cherokee and African fables, outwits figures of authority, aka bad guys. What storytelling can we expect to emerge from Syria, Gaza, Sierra Leone, El Salvador or Ukraine? Or Ferguson, Missouri?

Many southerners, black and white, are fundamentalist Christians, meaning that they are deeply schooled in the teachings of the Bible and accept them as truth. The influence of the 1611 King James Bible, often the only cultural possession in southern households, with its archaic language and imagery, can’t be underestimated. What is the Bible but a collection of vividly told stories, and the preacher an interpretative storyteller? It’s not a stretch to say that Biblical storytelling sparked imaginations – think of Genesis, Exodus, or the fire and brimstone, violence, monsters and apocalyptic events in Revelation, for example. Verily, verily I say unto you…

The backdrop for the storytelling – the stage set – is the exotic environment of the South. Visually, it is breathtaking, and early English naturalists like Mark Catesby, John Lawson and William Bartram came here and wrote and drew profusely, trying to capture the look and feel of it for folks back home. There are seacoasts, islands, swamps, caves, mountains and powerful rivers. The legendary 16th-century Lincolnshireman Captain John Smith described what he thought was the Edenic Chesapeake Bay area as “a country that may have prerogative over the most pleasant places of Europe, Asia, Africa, or America… heaven and earth never agreed to frame better a place for mans habitation”. The critters alone are a magnificent, Revelationary array: possum, bear, panther, cotton mouth and coral snakes, catfish, crawdads, coons, gar, bobcat, nutria, cooter, bats. Alligators! Armadillo! Mosquitoes, boll weevils, and two-inch flying cockroaches! The Essex gentleman Catesby said of the cockroach, which still plagues southern homes: “These are very troublesome and destructive Vermin, and are so numerous and voracious that it is impossible to keep victuals of any kind from being devoured by them.” Lowlands of the region are jungly, overgrown with kudzu, poison ivy, Spanish moss, wisteria, fern, honeysuckle, cypress knees, palmetto, ancient cedar, sprawling live oak and magnolia, not to mention vast fields of tobacco, cotton and soybeans. It seems safe to say, given the near-failure of the Jamestown colony, that Captain Smith had yet to experience the crazy anomalies of weather in the South; we don’t have snowstorms here as much as we have treacherous ice storms, and there are increasingly frequent, calamitous hurricanes, tornadoes, floods and drought. The heat and humidity is brutal (as I write this the temperature outside is 97°F, the humidity 70%), and in the days before air conditioning and TV, southerners spent time on their porches shelling peas, (black eye, not the round, green kind that we call ‘English peas’), paring peaches, reading the Bible or the Sears catalog, or just sitting, trying to keep cool, but talking, talking, talking. And listening.

To me, given all this, the history and religion, and the extraordinary physical world, the question would be, how could the South not have inspired so many writers for so long?

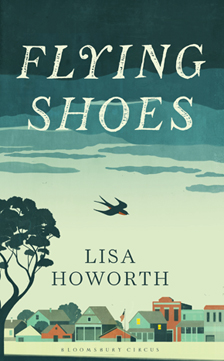

The tradition continues in Oxford. Writers are drawn here, some by the ghosts of Faulkner, Barry Hannah or Larry Brown, or by the thriving creative writing program at the University. Of course, much has changed, but much remains. Monuments to the Confederate dead still stand at the entrance to the University (nearly the entire student body of 1861 went off to war and met with 100 per cent casualties), and on the town square. But there is also a monument to James Meredith, the first black man to enroll at ‘Ole Miss’, a plantation-era nickname that has just been officially retired. Even this small Mississippi town has been brought – maybe dragged – into the 21st century. Some of the younger writers here now look toward other inspiration in the wider world, no longer so concerned, or maybe bored with southern themes. But others who’ve come to Oxford – Jesmyn Ward, Chris Offutt, Tom Franklin, Beth Ann Fennelly, Ace Atkins – continue to find what they need to write about in the South’s past, or its legacy in ongoing struggles with race and poverty, its music, its indomitable spirit. Old themes, new interpretations and demographics. Maybe it’s my own rage to explain, but I think there is always something new under our blazing sun. In my novel Flying Shoes, set in Oxford, Teever Barr, a homeless African-American Vietnam vet, gets ‘cross-wise’ with white folks, Vietnamese and Mexican immigrants. As Teever might say: there’s sumthin’ every day. Every single goddamn day.

Lisa Howorth was born in Washington, DC, in the area where her family has lived for four generations. She moved to Oxford, Mississippi, where she married her husband, Richard and raised their three children. They opened Square Books (named by Publishers Weekly as the 2013 Book Store of the Year) in 1979. Flying Shoes is a work of fiction, but the murder at its heart is based on the still-unsolved case of Lisa’s stepbrother in 1966. It is published by Bloomsbury Circus. Read more.

Lisa Howorth was born in Washington, DC, in the area where her family has lived for four generations. She moved to Oxford, Mississippi, where she married her husband, Richard and raised their three children. They opened Square Books (named by Publishers Weekly as the 2013 Book Store of the Year) in 1979. Flying Shoes is a work of fiction, but the murder at its heart is based on the still-unsolved case of Lisa’s stepbrother in 1966. It is published by Bloomsbury Circus. Read more.