The first bride

by Naomi HamillThey went crazy for weddings after the war. All weekend long, the shooting of impotent bullets into the air, the aggravating honking of horns and the incessant drone of the traditional Albanian music. As if they were so glad to be alive that they wanted everyone from Podujevo to Pristina to Tirana to know about it. We are alive, we exist, we are marrying, we are playing our choice of music, we are wrapping ourselves in the fierce red of the Albanian flag, we are driving expensive cars that we didn’t pay for and we are having babies and we are eating our turshi and carrying on our ways of living. Perendi ke meshire per ne.

Of course, it took a while before all this started. The confidence didn’t come at first. At first they were like spiders, scurrying from house to house, the grey grain silo towering over them. But when they could walk from house to charred house, only looking over their shoulders once to see if they were being followed, they began to feel better. When the schools started back and the hospital opened and UN tanks were seen only once in a while, then they trusted that they might be okay. The war is over, thank God, falenderoj zotin, they would say. Faleminderit Tony Blair, our hero. Faleminderit Bill Clinton, the greatest leader America has ever seen. We are free. We will live. We will marry. We will move on.

It must be traditional, the fathers would say. A traditional wedding. An Albanian wedding. A wedding we can be proud of. We are survivors and we will live our lives.

So, the girl, for she was only seventeen at the most, perhaps sixteen or maybe fifteen, would be made to look twenty-seven, with the dark painting of the eyes flicking with drama at the ends and the bejewelled dress that clung to every part of her miniature frame, showing that she was a woman, she was ready. She must look modern. She must look expensive. She must look American, British, Albanian. No, she must look Kosovan.

But she must not smile. She is sad to be leaving her esteemed family. She cannot bear to be parted from them. She is full of sorrow for the respectable father and the loving mother she is forsaking. That is, if the mother and father have been left for her. Otherwise it will be an aunt or an uncle, arranging this marriage in place of them.

In the overcrowded classroom, she whispers to her friends about her engagement, the elaborate plans for the wedding, the glamour of it all. She knows that amongst her friends she is seen as special.”

Of course, she is moving to another esteemed family. But for now she is full of the bitterness of parting. She will not raise a smile or rejoice in her humanity, still intact, though jeopardised by fighting. Not that she can remember much of that anyway. The frozen nights in the hills are just a far-off memory, or does she only even remember them because of the recitation of the stories by every adult in her family? Not every adult, of course.

No, she will stay serious and she will not smile. She will set herself apart, the portrait of the distressed woman, and play the part of the dutiful daughter of Albania.

But inside she is so happy, of course. A suitable man from a suitable family. A traditional family. A family with honour and dignity. An Albanian family. A Kosovan family.

She is the first of her class at school to be married. Whilst learning English in the overcrowded classroom with the scowling teacher who wishes the class would pronounce ‘night’ properly, she whispers to her friends about her engagement, the elaborate plans for the wedding, the aunts and uncles travelling from Germany, the glamour of it all. She knows that amongst her friends she is seen as special. The first bride. Married before she finishes high school. She’ll have a husband and a lover. The girls giggle over the idea of a lover. She does not tell them that he has already begun to teach her what he wants from her. She cannot look at her hands as she remembers where he has asked her to put them. She supposes that this is part of the pathway to becoming a wife. And now she knows things that the other girls do not know, wifely things. Things never spoken of by anyone. And that is what every girl wants.

She chose him herself, of course. He is a friend of her older brother and he was at her school. He began to talk to her when he visited the house. Slowly, at first. Respectfully. And then he made her laugh and told her she was bukur, so beautiful. He sent teddies, dresses, sweets for her mother. He deals in the clichés of love. But she has been taught to expect these tokens, to expect these things and the new names: sweetheart, darling, zemer.

And his family, his father, come to talk to her family. Serious talk in the living room. She cannot be a part of this, but she knows that her father is defending her honour. She knows that he is making it clear that if this boy, this man in the making, does not honour his daughter and marry her now, now that he has shown a clear interest, that his family will find that boy and will hurt him so badly that his face will ache into the sweating summer and the unkind winter of the next year. That his hands will bear the scars of betrayal for the rest of his life. And that, although he has slim chances of employment anyway, he will never ever find a job in this town, should he let her down. Her father smiles but he is not really smiling. And he lectures for a while, of his daughter and his family’s honour. And he says that she is not to be left now. That they will marry, that he will not have his daughter rejected by other men, because she has been pursued by this one. This is all said in the loud and friendly tones of jovial conversation, over Russian tea and the stirring of the thick Turkish coffee. They are friends, their families know each other from old. This family rode in the tractor with his grandfather, deep into the precarious safety of the hills. But they both know that this all must be said. There will be no parts missing from the ritual, the contract, the tradition. And he means it, every word that’s uttered.

Abandoned Soviet T-55 tank used by the Serbian military near Prizren, Kosovo, 2005. Mika Rantanen/Wikimedia Commons

At school she is special, the first. The teachers congratulate her, smile. She is a good girl, she is learning well. Able to do mathematics, she can speak English proficiently and her portraits of her classmates are pleasing. A good girl who deserves this happiness. Of course, there is one teacher who looks at her but does not dare to speak. She teaches her geography and when the girl answers a question in class, instead of responding to tell her if she is correct or not, the teacher stares sadly into her face. The others laugh and say that the teacher was always a little strange, but the girl doesn’t join in the mocking. Inside, maybe she knows.

The wedding day is electric. All around her she sees women made to look like film stars, dresses clinging to every line of flesh, made with the most expensive, cheapest of fabrics. They are watermelon green and pink, the pale yellow of the abundant peppers in the market, the azure blue of the plastic buckets found outside every shop in the town. They are ready to go to the Oscars, ready to prove to the world that they are beautiful, elegant, modern women.

She sees an aunt with shoes that take her breath away. The hundreds of diamante pieces wink at her with excitement. The straight back of the heel. That heel is so proud and aloof. It is so glad to hold up this beautiful specimen of a woman, with her peroxide hair and the thick, theatrical arches over the eyes, revealing a daring that doesn’t really exist. The woman knows that her shoes will cause excitement amongst the other women. They were sent by her brother in London and she tells them so. She is proud. She hopes that she might visit him one day, she says, although she, and the other women, know that the visa would never be allowed.

Still, they smile and they greet each other. The men with their sincere handshakes followed by the placing of the hand on the heart. We love our people, this placing is saying. We mean what we say. We are a people once more. We are honourable men. Of course, we do not talk about the browser histories in the internet cafes, or what happens in the woods, unreported, some days. We are honourable men. We will live our lives.

And the women. The women are preened to perfection. Some can hardly walk, others can hardly breathe, but they look astounding. They have taken all week to prepare for this wedding and the twinkle of the plastic jewels and the shine of the surprising dresses and the Albanian red of the lips, ready to kiss each other in greeting, show that it has been worth it. It is a wedding. We will look glorious.

The women hold their hands, linked, into the air, each forming a bridge that, unlike Gredelica, will not be broken. We are a nation, they are saying. This is how we dance and we can carry on all night.”

As the music begins, the women take to the floor. There is no need to think, as the one, two, three and back of the dancing that they learned when they were just girls comes as naturally to them as walking. Their faces hide any sense of excitement or embarrassment or joy or sadness. They will remain blank, their eyes staring, glazed, as their legs take over. The women hold their hands, linked, into the air, each forming a bridge that, unlike Gredelica, will not be broken. We are a nation, they are saying. This is how we dance and we can carry on all night. There is no need to think. This is part of who we are. The woman on the end waves a small handkerchief, but there is no energy lost in this action. It is as though the rhythmic movement of her arm is as much a part of her as the chopping up of the peppers, or the mixing together of the flour for the flija, or the steady weaving of the intricate yarns into jackets and tablecloths, or the carrying of her child into the mountains to some sort of nervous safety. The line of women travel the floor, each connected, each showing that she is now a proud mother of Kosovo, a sister, a daughter, a wife, a friend.

She has never seen anywhere as beautiful as this. It was paid for by the shacat, the sweetie pies, as they affectionately liked to call them. Those who got out during the war and now were so rich that they could send back money from Germany and could arrive for the summer in their Mercedes and drive them boastfully round the town. They must be so wonderfully happy, those shacat, she thought. And so kind. She was so grateful to her uncle for paying for her wedding without question. She did not know that this whole wedding was pitifully cheap by German standards.

This wedding must be spectacular. Of course, they all know that after the wedding, when she is a wife, there will be scrimping of euros and turning off the generator if the salary isn’t paid, and the grateful relief at the gift from Germany each month. But for now, they will shine.

The music fills the place. The enticing mix of Eastern and European sounds. It leads the dancers on, through the evening and around the room, entrancing them all. The men will join in later and will show their honour by their enthusiastic flinging and flicking. They will swivel their arms in defiance and scoop their legs from one side to the other in careless abandon. It will get noisier and the children will melt to the sides, sleeping on golden hotel chairs. The women will pick at crisps and drink Fanta. The men, outside, will smoke their cigarettes. The music will continue. They will dance for the entire evening. They will live their lives.

The Kosovan bride will remain in her chair. Although she is not smiling, they all know that this is the most glorious day of her life. Later, when they are ready to leave, they will pin notes to her and kiss her and wish her love and blessings from God. Her face will stay emotionless, of course. She is a good girl and she will show respect to her family.

The Kosovan bride will not be found by her older cousin in the toilets of the expensive hotel, so expensive that she has never seen such luxurious handwash before, locked away and stubbornly trying not to cry. She will not be afraid of what will come next. She will not insist that she cannot, will not, let this man, this disgusting boy, touch her again.

All this will not happen. You will not let it.

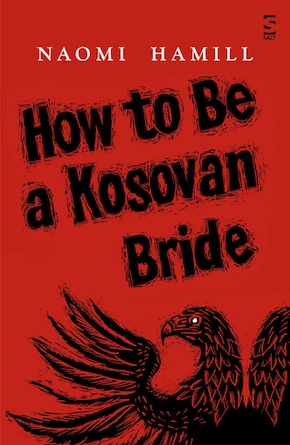

From How to Be a Kosovan Bride (Salt Publishing, £8.99)

Naomi Hamill was born in Wales in 1979 and grew up in Hampshire. She has an MA in Creative Writing from Manchester Metropolitan University and works as a secondary school teacher in Manchester. She has been visiting Kosovo for over ten years, with the charity Manchester Aid to Kosovo. She has heard many stories of those caught up in the 1999 conflict and been a guest at many Kosovan weddings. How to Be a Kosovan Bride is out now in paperback from Salt Publishing.

Naomi Hamill was born in Wales in 1979 and grew up in Hampshire. She has an MA in Creative Writing from Manchester Metropolitan University and works as a secondary school teacher in Manchester. She has been visiting Kosovo for over ten years, with the charity Manchester Aid to Kosovo. She has heard many stories of those caught up in the 1999 conflict and been a guest at many Kosovan weddings. How to Be a Kosovan Bride is out now in paperback from Salt Publishing.

Read more

@naohamill

Author portrait © Paul Cliff