Business

by Linda MannheimYou’re standing outside the bar on 104th Street and Broadway, the rain beating down like it means you harm at first, then dissipates so all it does is leave the street slick and smooth as a sheet of marble. You inhale that smell of wet pavement you’ve known forever, and the city shines back at you. The light stretches across the street and plays in shapes that change when the wheels of the cars hit them.

You huddle back in the doorway; your expensive, clean trench coat around you that you’re angry has gotten wet, doesn’t seem so new anymore. And the edge of your straight, black hair has gotten damp, and you’re afraid you don’t look like what you are, that someone will mistake you for what you once were. And when a beat-up brown Chevy pulls over, you start to go to the sidewalk’s edge because you think it’s him, but it isn’t. It’s just someone street-looking and scrappy, baseball cap and Bronx walk and B-Boy clothes, who says to the man in the driver’s seat, Just a minute, man. I’ll just be a minute. I just gotta get something.

You look at your watch, wind your way out and turn your head to see up the street as if you’re waiting for the bus, waiting to get taken somewhere. He’ll be coming from uptown. He’ll be coming from where you come from.

It returns to you, with that smell of water on pavement, where it was you went when you first came to this neighborhood. The gated entrances to CCNY appear as if they were right before you; the gothic campus of the City College of New York, free back then. It was only later, when a minority of the students there were white, that they started charging tuition. The stone buildings stood like a bet laid on hauntings, their gargoyles warning you away even as you told yourself again and again that those buildings would be your salvation.

That was the year the government was dousing Southeast Asia with napalm. A picture of a girl screaming as she ran naked and bearing her burns stayed with you all that fall. You drank beer with the boys and reported your nightmares at the West End Bar. And that spring you had a plan. You were going to stand up and repeat your nightmares to the class, and tell them, No business as usual. And Sonny, Robert, Ada, would all stand. And the others, who had not planned to stand, would go with you to the next class, and more would come, until the march snowballed so that thousands of you would make your way across campus chanting, No business as usual. But it didn’t go the way you’d planned. You all stopped when you saw the flames, no one knowing who threw the fuel, who tossed the match, as you watched the ROTC building burn.

After that, there was Yvonne Carter, and the twenty-three children who lived with her, some adopted legally, some not, all squatting in a building the college said they needed for student housing. She had a payphone in her kitchen, an endless supply of people who sat in the kitchen talking, mimeographed leaflets that sat in stacks. You slept on the living room floor. One night, one of her sons came home, hollow-eyed from Vietnam. He knew, he told you, how the heroin was coming into the city. It was flown in on military planes.

You turned from him, tired of tirades, weary of conspiracy theories.

Six months later, he was shot dead. Found on the roof of a building nearby – a single bullet to the head.

This is the safe place to come from where you live, the safe place to buy. Because you can’t go back uptown, you can’t cross the line. Things have gotten so bad. Even back on 83rd Street, there’s been some violence. It’s those SROs between the co-ops, all those people from the shatter-glassed welfare hotels out on the stoops when it’s hot because there’s no place else to go. You know Ellen’s scared of them, wondering if it was a good idea for her to move to the city, even though she used to come in all the time when she was growing up. Anyway, it’s interesting, she says. And she loves the cafés here, and the bookstores, and Zabar’s bread. Be careful, she tells you, before you go out.

She tells you stories about her growing up and the boring Boring BORING suburbs, and how hard it was to get away, how hard it was to get around before she learned how to drive. And you say nothing. You don’t tell her about the beating of the pipes in the building when the heat wouldn’t come, you don’t tell her about the bullet trade in high school, you don’t tell her about the best way home – avoiding all the places you should never go. You just smile and make jokes about how tough it was there, and, yeah, of course you can get some horse.

You’re standing in the doorway, waiting for the man to come, waiting for the cranberry BMW with Jersey plates. It comes and you go, open the door just enough so you can hand him the cash and he hands you the tiny bag, and you take it like it’s a ticket home, the cellophane smooth in your palm. You reach back in and shake his hand, automatically giving him that forced smile you save for all your business transactions.

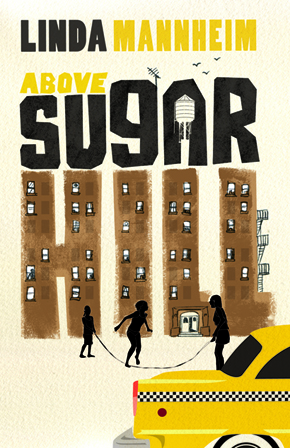

From Above Sugar Hill.

Linda Mannheim is the author of the novel Risk, written while she was a visiting associate at the University of Cape Town’s Centre for Africa Studies, and the story collection Above Sugar Hill, now published by Influx Press. Her stories have appeared in Nimrod International Journal, The Gettysburg Review, New York Stories and New Contrast. She lives in London.

lindamannheim.com

“Linda Mannheim’s smouldering vignettes of New York life are both achingly sad and beautifully wrought. These are stories to re-read and savour.”

– Stuart Evers