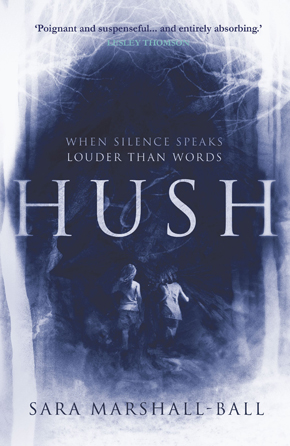

Capturing the silence

by Sara Marshall-Ball

“A marvellous debut… haunting and unsettling.” Peter Boxall

I never deliberately set out to write a silent character. I know it sounds like a writerly cliché – “they just walked into my head like that”, and so on – but in Lily’s case it’s completely true. That’s just the way she was, and it never seemed particularly unusual to me. So when I entered Hush into Myriad’s First Drafts Competition (then the Writer’s Retreat Competition), and the judges started talking about how unusual it was to have a character who doesn’t speak, it made me reassess what it was like, working with a character like Lily; it made me wonder whether I’d done anything particularly new or difficult.

I imagine if I’d ever thought about what it might be like to write a largely silent character before I actually started, I would probably have found it daunting, and maybe even given up without trying. For a start, how do you convey what your character is thinking and feeling if they won’t tell you about it? It’s one thing when it’s a passing phase, but when it continues into adulthood, as it does with Lily, this becomes more tricky. It’s this, I think, that makes her unusual: her difficulty with speaking in virtually all situations, at all points in her life, rather than just an aversion to speaking about one difficult event.

As an exercise in character development, writing her was actually pretty useful, because it made me notice how rarely we explicitly express what we’re thinking and feeling. I’d been taught years ago that having characters who walk around parroting exactly what they feel was unlikely to make compelling reading, but it was really interesting to restrict myself almost completely to Lily’s actions, and to other characters’ interpretations of those actions. One of my favourite things about Lily and her partner Richard’s relationship is the way that Richard gathers clues, to try and guess what she is thinking at any given time, and as the writer I often felt like I was in the opposite position – planting clues for the reader’s benefit.

I was also determined not to fall into the trap of telling rather than showing what Lily’s motivations were. It would have been easy enough to give a running commentary on her thoughts, but I was more interested in seeing Lily in the way that other characters saw her, which meant relying on expression and movement to convey her character, rather than waiting for her to tell me what she was thinking. Because of this, her relationships with the other characters became that much more important. It was through her interactions with them – and their perspectives on her – that she became a much more genuine character. From the moment I met Lily’s sister Connie, I had the sense that she was overprotective and somewhat overbearing, but it was harder to pinpoint why this was the case: it was only through the process of actually writing the novel that I figured out what it was in Lily’s behaviour that made Connie act in that way.

The majority of SM sufferers are actually only silent in certain situations, and generally go on to be precocious speakers in later life, unlike Lily.”

Another major concern for me was making Lily’s silence feel justified and realistic. This wasn’t necessarily related to making her fit the profile of a typical sufferer of Selective Mutism – the majority of SM sufferers are actually only silent in certain situations, and generally go on to be precocious speakers in later life, unlike Lily – but I wanted to make it clear that this wasn’t just a fictional construct, or a convenient plot device, but a genuine and intrinsic part of her character.

The most important part of this, for me, was creating a believable way for her to start talking again. It would have been easy, and probably more dramatic, to have some revelatory moment where her anxiety lifted and suddenly she could speak in full sentences again; but this didn’t seem to ring true. Rather, I wanted to make it clear that learning to talk again took years of practice, and that she still struggled with it into adulthood.

That said, her career as a university lecturer might seem like an odd choice. But for me it perfectly summed up everything I wanted to convey about her attitude towards speech: she’s physically capable of speaking. If she deems it necessary, as an adult, she will speak. But that doesn’t mean she wants to.

Writing Lily has definitely felt like a learning experience for me; she has made me a better writer in many ways, from thinking more carefully about my characterisation to, oddly enough, writing better dialogue (if you have so little of it, you have to make every word count, after all). But more than that, bringing her to life was probably the most enjoyable part of writing Hush: it almost felt like an honour, to be able to tell the story that she was unable to tell herself.

Sara Marshall-Ball grew up in Cambridge and studied English and Creative Writing at the University of Derby before moving to Brighton to complete an MA in Creative and Critical Writing at the University of Sussex. Hush, her first novel, was shortlisted for the Writer’s Retreat Competition in 2012 and is now published in its final form by Myriad Editions.

Sara Marshall-Ball grew up in Cambridge and studied English and Creative Writing at the University of Derby before moving to Brighton to complete an MA in Creative and Critical Writing at the University of Sussex. Hush, her first novel, was shortlisted for the Writer’s Retreat Competition in 2012 and is now published in its final form by Myriad Editions.

Read more.