Catching the past

by Mika Provata-CarloneIn 2014, Otto de Kat wrote a short essay for PEN, where he gives a poetic yet also practical definition of the art and skill of writing historical fiction, of crafting novels whose life must be fictional, and yet feistily rooted in factual reality. This genre has been his own home since 1998, when he published his first novel, The Figure in the Distance. Memory, history, the individual and its place in a world in dramatic flux are his constant themes, as are the relationship and parallels between Dutch and German history, Holland and Germany as nations with a specific cultural and political identity and past, before and after World War II. In each novel, de Kat creates worlds of relentless solidity but also worlds of perpetual evasion and abstraction – and the two are vitally interconnected, as though each were the key to the secret of the whole.

Urban versus rural life, idyll versus reality, existing in the historical moment as opposed to subsisting in time, these are the driving forces defining tensions and deciding lives. Personal responsibility before history is a question constantly raised, perhaps never clearly answered, as crowds and mobs overwhelm the impetus to action of single, singular lives. An individual with a sense of duty to respond, react, resist, must break down the walls of individualism, of indifference, of moral sloth or cowardly self-interest – must confront and defeat the ruthless determination of ambitious mediocrities. De Kat’s characters belong to Dutch or German families with long and rich bourgeois backgrounds, tactile stories and histories unravelling myths of colonial or industrial splendour. They also bear the burden of the guilt of privilege, which drives them to philosophical journeys or biographical errantry.

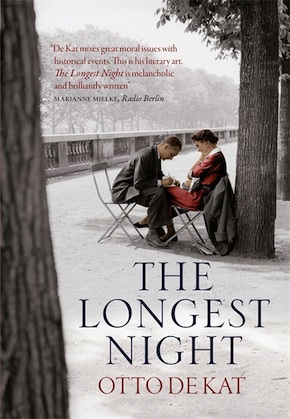

Each time, memory is like a hot coal in the hands – the characters’, the author’s, the reader’s. Memory seems to be the Janus face of life, and yet at the same time it is what confronts it, questions it, unsettles it. De Kat’s books, and especially his latest to be translated into English, The Longest Night, are tireless attempts to solve the puzzle of human remembrance: its tenacity, selectivity, its inalienable grip on human experience and consciousness, its flickering fragility, its deluding or revelatory powers. Private, public or historical, memory is at the centre of each life, the life-thread of humanity itself. There is a constant struggle between memory and forgetting, between the fullness afforded by recollection, by the vital community created by these retrieved moments and sentiments of being, and the unbearable stripping down of emotion when memory represents the re-enactment and unalloyed re-experiencing of loss, trauma, devastation, or simply, brutally, the severance of stories, the removal even of an end to be remembered.

What are the rules of engagement with the past? This seems to be the critical dilemma of every life, and the lives of individual women or men constitute in de Kat’s world the prism of perception, the scale of value and of existential and moral significance. The silent echo to this is the craving for a release from remembrance, for total escape once it is all over – for a ‘palliative sedative treatment’ to everything that renders life all that it is. The Longest Night is perhaps the culmination of that questioning – informed, in very clear terms, by de Kat’s own training as a theologian and phenomenologist philosopher, and as an art critic used to dealing with aesthetics, with the quintessential value and price of appearances, of form and substance.

The ancient Greeks and Romans knew that one of the foremost precepts of a good, long life was learning how to die well – by being skilled in the art of living.”

An old woman, who has been a child and a young woman along de Kat’s narrative trail, is given to us in the frail rawness of her last hours – as chosen by her, as determined by a team of specialists in assisted dying, who are “silently at work. Words were the enemy, silence their best camouflage.” On a very fundamental level, this slim volume is about how we die, our relationship with our own mortality – and the mortality of those dear to us and close to us. The ancient Greeks and Romans knew that one of the foremost precepts of a good, long life was learning how to die well – by being skilled in the art of living. This eschatological compass to life was also at the core of Western civilisation in all its various forms of pietism, memento mori, vanitas, esotericism or hesychasm, a deeply philosophical ars vivendi or rebellious secularism.

Modern mankind seems to have lost that art or even the will to consciously refute it. We seek the entitlement to immortality through our claim to the right of absolute ephemerality and the erasure of memory. Our culture and way of life barely acknowledge death and dying as part of what the Stoics called ‘our business’, the matters that concern us. Death is no longer the terminus of a life well-cherished but the injustice we must constantly resent and fight against – often reacting to it by egotistically embracing its mechanics, making our own self-annihilation through suicide or the wilful wasting of a life (both patterns de Kat develops persistently), our triumph over and escape from the factuality of our human condition. We twist the philosophical and metaphysical notion of a beautiful death – which presupposes a deeply appreciated life – into a will to die, a moribund self-indulgence of perverse provocation and challenge.

This very art of dying, the necessary, other side of the art of living, is at the centre of de Kat’s novel, which could be defined as the quiet afterthoughts of many stormy lives. Several stories intertwine, life experiences clash, blend or complement one another with an expectation of ultimate catharsis and revelation. Several roads to the end of a life are picked up and scrutinised under an almost blinding, isolating light, as past and present flicker alternately, as in an old-fashioned, phantasmagorical magic lantern. Euthanasia and palliative assisted dying, suicide and self-destruction, natural death versus brutal execution and murder, lonely death; ghosts and real lives commingle, to confirm that “it is death that awakens us” to life. It is a search for a purpose in a life now expended, in order to exorcise traumas or ourselves.

On a personal level, this is a journey of faith and disbelief, of hope and dejection, of sincerity and delusion. Emma, the old woman with the long past, ‘speaks’ in elliptical thoughts, images and phrases, especially in broken lines from long-forgotten (or long-remembered) poems. Hers is an eerily selective viewpoint, with great holes in historical, moral or even autobiographical details. It is suffused with references, echoes, a pregnant ambiguity throughout, a determined attempt to both engage with and avoid substance (as she is reminded by her nurse, she must choose to subsist on emptiness and nothingness in order to die). We cannot fail to be moved, jolted, captured by this last hero’s song, as it often seems.

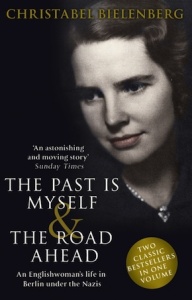

It is a bold, provocatively daring narrative edifice, with an unwavering sense of unfulfilment. Behind the “dossiers of helplessness” that are the personal narratives intruding on and altering Emma’s final script of her life, lies a tremendous mountain of history – as well as de Kat’s previous novels, all of which contain the vital links and developed storylines. As readers, we require specific and extensive historical knowledge in order to follow the “crumpled map” of Emma’s memory, perhaps also some of the fictional biography from the companion novels. “Writers are catchers of the past; writing is an attempt to get a grip on the things that were, and another word for melancholy; writing is a fight against forgetting,” de Kat wrote in his PEN essay, and the past he seeks to catch here is the Kreisau Circle, the Claus von Stauffenberg plot, the untold story of German resistance to Hitler and Nazism, as evinced through the particular stories of Adam von Trott and his wife Clarita, more indirectly the Anglo-Irish writer Christabel Bielenberg, who provides a hazy mirror image of Emma as the foreign wife to a German state official, and of Peter Bielenberg, who survived the war, the Stauffenberg plot, and the faint attempts at denazification by the allies, to become a happy Irish farmer.

It is a bold, provocatively daring narrative edifice, with an unwavering sense of unfulfilment. Behind the “dossiers of helplessness” that are the personal narratives intruding on and altering Emma’s final script of her life, lies a tremendous mountain of history – as well as de Kat’s previous novels, all of which contain the vital links and developed storylines. As readers, we require specific and extensive historical knowledge in order to follow the “crumpled map” of Emma’s memory, perhaps also some of the fictional biography from the companion novels. “Writers are catchers of the past; writing is an attempt to get a grip on the things that were, and another word for melancholy; writing is a fight against forgetting,” de Kat wrote in his PEN essay, and the past he seeks to catch here is the Kreisau Circle, the Claus von Stauffenberg plot, the untold story of German resistance to Hitler and Nazism, as evinced through the particular stories of Adam von Trott and his wife Clarita, more indirectly the Anglo-Irish writer Christabel Bielenberg, who provides a hazy mirror image of Emma as the foreign wife to a German state official, and of Peter Bielenberg, who survived the war, the Stauffenberg plot, and the faint attempts at denazification by the allies, to become a happy Irish farmer.

There is a constant converging of stories of bravery, violence, war and devastation, love, peace, forbearance, the rickety dream of a reconstructed life, as well as a sense that right and wrong were not always clear.”

De Kat’s method is, as he has said, to invert the roles of magnitude, making “the big events smaller and the smaller events bigger.” In The Longest Night, it may seem that this process sometimes loses its measure: the snippets are too minimalist to form a picture or even an impression beyond that of a beautiful, pained, deeply fragmented memory. His scope is grand and of importance: to question easy categorisations, to offer us fleshed-out, fully palpable lives, to remind us and warn us, intrigue us into a historical as well as a personal journey. He succeeds in evoking, in the style and tone of this novel (Laura Watkinson’s translation skilfully sustains this throughout), the particular charm but also vagueness, intimacy yet also distance of Christabel Bielenberg’s own memoirs, which constantly provide points of anchorage, the sense of an era but especially the psychology of before and after.

Emma expresses criticisms of historical assessments in the same way Bielenberg does, particularly in her private correspondence: there, as in The Longest Night, Holland’s colonial past is starkly, unflinchingly set up beside Nazi actions and intentions. In de Kat’s novel Israel is also hinted at, with delicate, annotated cameos: of Mea Shearim, the Orthodox and oldest neighbourhood in Jerusalem, “the neighbourhood of heavyweights”, Emma recalls “dark figures with books under their arms, swaying, half-singing, an opera without women, which they watch and listen to from their taxi, with respect and incomprehension.” Jerusalem itself is “the tragic city built from ancient myths, lies and revelations. Wherever you look, you see an armed dream, a vision firmly fenced in.” There is a constant converging of stories of bravery, violence, war and devastation, love, peace, forbearance, the rickety dream of a reconstructed life, as well as a sense that right and wrong were not always clear, as though an entangled ethics were the only secure reality: “this was how to walk and to live and to love and to outwit death… free and with no history.”

This is a tenet constantly put forth, tirelessly questioned throughout the novel, as Emma moves between states of enchantment (the intangible energy of a world at war?) and disenchantment. The undercurrent is that memory is not only to be possessed and owned to, but it must also be transmitted to succeeding generations – one has, especially, a debt of providing a historical voice for the future. By choosing the stories of the Bielenbergs and the von Trotts, what is at stake, on a more formally historical level, is the nature and moral assessment of German opposition to Hitler, but also the reluctance, even refusal of the British and US political and intellectual status quo to give credence and support to that opposition. In 1969, David Astor, a close friend of Adam von Trott since Balliol, wrote in The Encounter an article entitled “Why the revolt against Hitler was ignored”. In it, he points out that to see von Trott and others as Good Germans “involves the possible admission of some British share of responsibility, even if only passive responsibility, for terrible events.” Emma repeatedly echoes this statement, often as a true insight into the complexities of the pre-war period, equally frequently as her own ‘palliative sedation’ against the necessity of a personal account and memory.

De Kat uses this duality as his particular tour de force, if one can claim that the novel aims at such an element. He does not offer closure in any distinct or even abstract form, nor a hermetic context of judgement or even sympathy. What he does provide us with is a tantalisingly inconclusive, rich narrative, where the burden not only of interpretation but ultimately of a cohering conscience lies exclusively, so it would seem, with the reader.

Otto de Kat is the pen name of Dutch publisher, poet, novelist and critic Jan Geurt Gaarlandt. His award-winning novels have been widely published throughout Europe. The Longest Night draws to a climax elements from three previous novels published by MacLehose Press: Man on the Move (2009), Julia (2010) and News from Berlin (2014).

Otto de Kat is the pen name of Dutch publisher, poet, novelist and critic Jan Geurt Gaarlandt. His award-winning novels have been widely published throughout Europe. The Longest Night draws to a climax elements from three previous novels published by MacLehose Press: Man on the Move (2009), Julia (2010) and News from Berlin (2014).

Read more.

Author portrait © Tessa Posthuma de Boer

Laura Watkinson is a translator from Dutch, Italian and German based in Amsterdam, whose projects range from adult fiction to children’s picture books and comics.

laurawatkinson.com

@Laura_Wat

Mika Provata-Carlone is an independent scholar, translator, editor and illustrator, and a contributing editor to Bookanista. She has a doctorate from Princeton University and lives and works in London.