Something better change

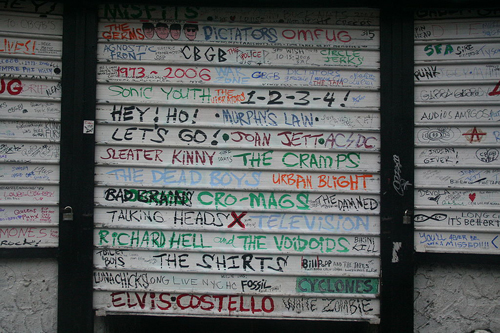

by Brett MarieThe opening shots of guitarist Ivan Kral’s documentary Dancing Barefoot are a series of home-movie clips from New Year’s Eve 1975 at the legendary nightclub CBGB. Over the brooding vamp of the Patti Smith Group’s cover of ‘Gloria’, Kral treats us to overexposed black-and-white shots of New York’s punk-rock royalty, ringing in the New Year at the epicentre of a massive movement that was at that moment reverberating throughout music and culture. To look back on this footage in the present day is to be confronted with two conflicting feelings. On one hand, we watch the parade of famous faces go by and marvel that such a pool of talent would congregate in one room. On the other hand, the sight of these supposed luminaries (Lenny Kaye and Jay Dee Daugherty of the Patti Smith Group, Tina Weymouth and David Byrne of Talking Heads, Richard Hell, Debbie Harry), blowing party horns, goofing around in cardboard hats, sometimes merely smiling and sipping their drinks, brings them down from their rock-star pedestals to a more human level. It shows CBGB not as the hallowed venue of myth, but as something more mundane: a great rock club – one of the greatest – but a rock club all the same, and a gloomy one at that.

‘CBGB will remain open,’ Van Zandt declared. Reading the news from my new home an ocean away, I remember thinking, Why bother?”

Twenty years later, all that remained was the gloom. For a couple of months in the Spring of 1999, for reasons more to do with my gonads than logical thought, I played lead guitar in a female-fronted hardcore punk band. It’s embarrassing today to picture myself wearing out my wrist trying to keep up with light-speed riffing and severe-ADHD chord progressions, wedging blues solos into ten-second instrumental breaks where they had no business being. I wouldn’t trouble myself with the memory if my tenure in that group hadn’t granted me forty minutes on CB’s stage. The famous grime and graffiti still graced the walls after two decades, and was in fact all the more visible, since there were few bodies in the room to obscure them. While the opening band charged through a dozen songs which I couldn’t distinguish from the ones we were about to play, our lead singer Liz flirted with the editor of a New Jersey punk fanzine. Scanning the beer-stinking gloom around me, I was horrified to discover that this man in a T-shirt and baggy shorts who was at that moment showing Liz his latest issue – a ream of Xeroxed paper stapled together on one corner – was the only person on the floor who was not either in our band or on CB’s payroll. Onstage twenty minutes later, surprisingly ungrateful that the openers had decided to stick around to catch our set, Liz hurled an insult at their singer which prompted them to walk out. Now, finding ourselves playing for fewer people than we had at soundcheck, that would have only been humiliating. But our night crossed a threshold into the bizarre near the end of our set, when I stepped to my right and bumped into Mr Editor – heretofore our last audience member – dancing an arthritic jig in the middle of the stage. At this moment, I realised I had accomplished two firsts: the feat of playing along to onstage choreography, and that of performing for an audience of zero.

Seven years later, when CB’s became mired in debt and had its lease expire, ‘Little’ Steven Van Zandt hosted a rally in Washington Square Park in a desperate attempt to keep the club from folding. “CBGB will remain open,” Van Zandt declared. Reading the news from my new home an ocean away, I remember thinking, Why bother?

“Warm and illuminating.” Mark Ellen, Sunday Times

I don’t feel particularly good about myself for having such callous thoughts, but I suspect Dave Haslam might understand them. If I could point to one quality that makes Haslam’s new book Life After Dark work as the most impressive chronicle of cultural movements I’ve read since Peter Guralnick’s Sweet Soul Music, it would be its resistance to sentimentality.

This is certainly not its only quality. I admire its ambition; spanning from the mid-nineteenth century to the present day, stopping off in just about every pub, in every wide space in the road from Land’s End to John o’Groats, the book aims to capture and put into words every instance of after-hours zeitgeist that ever made so much as a ripple in Britain’s popular culture. I like its authority; Haslam made his name DJing at Manchester’s famed Hacienda nightclub, and as a promoter, writer and broadcaster, he’s witnessed firsthand many of the latter-day social phenomena he covers. He’s no slouch when it comes to research, either; his attention to detail in early chapters, discussing events of which the only record is period newspapers and archival town council documents, makes descriptions of goings-on in Victorian music halls almost as vivid as the portraits of the late-80s Manchester club scene of which he himself was a part.

But as vivid as Haslam makes the events of a given night feel, he takes pains to remind us that that night is over. If a venue has been lost to history, Haslam will make sure we know what became of it. Sometimes he slips us the news in a parenthetical aside (the Expresso Bongo club in Morley, he tells us quickly, is now the Ho-Ho Chinese takeaway, while the Coventry Locarno is now that city’s central library). Often he will take us along with him as he tours what remains of a place. We’re told the story of Leeds City Varieties’ early heyday from the point of view of the guided tour Haslam takes a hundred and fifty years later. A chapter discussing the Dug Out, a basement venue that was such an integral part of Bristol’s music scene in the 1980s, begins with Haslam’s encounter with the owner of the Korean restaurant that now occupies its space: “Hyeonje Oh has never heard of Massive Attack and is a bit sceptical about the whole story I’m telling him… The Surakhan serves authentic Korean food. Mr Oh wasn’t expecting someone to walk in off the street wanting to look in his basement. He’s very polite and doesn’t throw me out. He offers me a menu. Korean food, he tells me, is spicy – ‘spicy tasty not spicy hot.'”

By rooting these club scenes so firmly in the past, and himself so firmly in the present, Haslam becomes that voice on the theatre PA, telling the screaming teenyboppers that Elvis has left the building. Haslam doesn’t want us reliving these past events like some Civil War battlefield re-enactment. (He’s genuinely alarmed, and has to flee, when he visits the relocated Cavern Club in Liverpool to find a crummy tribute act playing old Beatles tunes for tourists.) He wants us to seek our fun someplace new, as the characters in this long story have done time and again when their venues of choice have gone past their sell-by dates. This constant drive to find new and exciting avenues of entertainment, to try new styles of dress, dancing and self-expression, this is what keeps British culture vibrant. It’s what made London the centre of the universe in the mid-sixties with the rise of the Beatles and the Stones. It’s what gave us punk rock ten years later, and Britpop in the nineties, and countless musical and stylistic innovators before and since.

No, Haslam isn’t in this for the nostalgia, and he’s careful not to leave the reader yearning for some past club that’s now a parking lot. He is far more interested in presenting these scenes as part of one long, living movement. As such, he’s able to conclude on an optimistic note even as he touches on a round of venue closures that have come about in recent years. “What we’ve witnessed through this history,” he tells us, “is what might be called ‘the power of the cell’; how a tiny group of disaffected outsiders can create a sensation, or a movement, or even change the world. We’ve seen how important cultural activity invariably begins small-scale, maybe finding a focus in a grotty bar or a club or some barely selling magazine. And we’ve learned that, yes, the good life is out there somewhere. And that the best club in the world is the one that changes your life.” Primed by Haslam’s rich history of life after dark, we close the book and reach for a copy of the NME – or, more appropriately for today, log in to Facebook or hop on Google – cheerily scanning for a place to go tonight, looking to join that next late-night revolution.

Brett Marie, also known as Mat Treiber, grew up in Montreal with an American father and a British mother and currently lives in Herefordshire. His short stories such as ‘Sex Education’, ‘Housewarming’, ‘The Squeegee Man’ and ‘Black Dress’ and other works have appeared in publications including The New Plains Review, The Impressment Gang and Bookanista, where he is a contributing editor. He recently completed his first novel The Upsetter Blog.

Facebook: Brett Marie

@brettmarie1979

Life After Dark by Dave Haslam is published by Simon & Schuster in hardback and eBook. Read more.

Life After Dark by Dave Haslam is published by Simon & Schuster in hardback and eBook. Read more.

davehaslam.com

@Mr_Dave_Haslam