At the chopping board

by Simon WroeDibden’s section is sprayed with bits of fruit and crumb and peel. Spilt sauces and dark reductions are clotting like blood. Mint leaves tremble in his hands. His mouth is slack and open, his movements awry. His head folds one way, then the other. There is no use left in him. He is a punchdrunk boxer, a spavined horse, a former umbrella. We watch in silence.

“I want it now, spastic! Get it on the plate!”

Bob would like a raspberry soufflé that has been on for half an hour. He leans on his palms at the pass, poking his jowly, sweating head beneath the hot lamps to shout at Dibden. Big Bob, in all his petty, weaselly majesty. Cocktail sausage fingers, huffing like a spoilt child. The tyrant. The buffoon. The prick.

“Soufflé!”

And all the while the machine hacks out dessert checks and everyone else is too busy with their own drastic situations to improve Dibden’s. Soon Bob’s greedy fingers will poke their way into a ganache and deduce that all is not well there and his keen eyes will spy the crumbling pastry tarts and exhausted fondants and stewed raspberries and there will be separate, clearly labelled portions of hell to pay for each of them.

I started working in kitchens after university. Three years of literary criticism – the Marxist readings of Hamlet et cetera – had left me sick of words; of thinking, I suppose. I wanted something real. I wanted to chop onions all day and get burns on my hands. I wanted to wake up disgustingly early and be shouted out and have the bookish, cloistered boy kicked out of me. I wanted a place where talk of hermeneutics was kept to a minimum. I wanted somewhere with life, and I found it.

The first thing you notice about kitchens is the strangeness of the environment. There’s no place like it. The work ethic is Herculean. The language is a peculiar mixture of high and low: sophisticated French terms married to gross insults (a tone which I tried to keep when I wrote Chop Chop). But the oddest thing, for me at least, was the emotions that such a small, everyday thing as food provoked in people. Chefs, like the fictional Dibden in the extract above, suffered so much for little things like a raspberry soufflé. They experienced joy, grief, panic, stress, fear, hope, anger, arrogance, sadness, madness, bitterness, despair, excitement, curiosity, mastery, inspiration, consternation, nostalgia, neuralgia – not to mention more common, wholesale pain – and all over a bit of food! Humble scraps of protein and carbohydrate, everyday blobs of sugars and lipids, turned these poor souls inside out.

I know only one other place where a detail so slight and evanescent as food might get this level of attention, and that place is literature. Proust goes into raptures over madeleines, Tolstoy gets sentimental about wrinkled French pears (in fact, I seem to remember pears being key in more than one Tolstoy tome), and Joyce devotes plenty of time and gorgeous prose to Leopold Bloom’s breakfast of kidneys “which gave to his palate a fine tang of faintly scented urine”. Delicious. In Knut Hamsun’s Hunger, the first person narrator devotes most of his thoughts to what a steak might do for his spirits at the current moment. And in all these examples, food is never just sustenance. It always means more.

Increasingly, this intense, contained world of grotesque characters, with their very particular habits and desires, seemed a great place to set a novel. The claustrophobia and deadlines and personalities were a combustible mix.”

These details that stay with us in literature, magnified into significance by the writer’s eye, are writ equally large in kitchens. Right now, somewhere in the world, members of this noble profession are having nervous breakdowns over butter, or crying with joy that they have mastered an omelette. Kitchens are also places of rogues and transients – everyone there has a story. They are usually running away from something, and usually running straight into something else. They hoof drugs and booze in industrial quantities. They share a love of self-destruction, a wilful pursuit of sensation and oblivion, a natural inclination to the path of most resistance; they possess a great, insatiable appetite that overrides all else.

I kept thinking about these things after I left the restaurant business. Increasingly, this intense, contained world of grotesque characters, with their very particular habits and desires, seemed a great place to set a novel. Who could resist such a cast? The claustrophobia and deadlines and personalities were a combustible mix, a perfect pressure cooker for drama. Beyond this, it was a world that was largely unknown, despite the TV shows dedicated to it and the restaurants all around us. We sat in these places every week, with no idea of the madness unfolding a few feet away from us. I wanted to show people this alternate reality right under their noses. The idea wouldn’t let go of me.

Nor, it seemed, would cooking. For despite the obvious and myriad arguments against cheffing, I found myself missing it. Around seven in the evening I became agitated, preparing myself mentally for a dinner rush that never came. I devoured cookery books and prepared ridiculously elaborate dishes just to put myself up against it.

So, after a break of four or five years, I talked myself into going back into cheffing. I got a job at a restaurant near where I lived, a place highly regarded for its food. I started at the bottom again: the commis chef, the kitchen bitch, doing everything in the kitchen that other chefs didn’t have the time or inclination to do themselves. I quickly realised it is much harder to stand all day cutting chips or plating salads when you’re thirty than when you’re twenty-three. Physically harder, and mentally harder too. If you’re thirty years old and working in a British kitchen and English is your first language, you should have reached the rank of senior chef de partie or sous chef, removed from the donkey work.

But there was one other crucial difference: this time in the kitchen, I took notes. I hid myself in the walk-in fridge or the dry store and scribbled down things people had said or done; I kept a diary of my kitchen life. When I witnessed or experienced abuse, I wrote about it. My pen and notepad were always on my person, and when my shift ended in the small hours of the morning, I would go home and write up a fuller account, no matter how tired I was, to ensure I would forget nothing. If I questioned my decision to return to cheffing (and I frequently did), this assignment discovered the virtue of the act. Some days I am sure the thought of this secret mission was the only thing that kept me sane.

Finally, when I could stomach no more, I quit the kitchen and, between stints of work as a freelance journalist, pondered what to do with my notes. It took a while to find a way in, but eventually I decided the best path was the one closest to home: the university graduate with literary hopes, thrown into this mucky, profane world. I wanted him to tell the story of this kitchen, as seen through his disbelieving eyes. And I wanted the other chefs to push and chivvy him on, asking for facts and clarification as if they were the missing mains for table 38. If my protagonist got too pretentious, if he began to spout allusions as the characters of some modern novels are wont to do, these no-nonsense editors would stamp it out.

The result, I hope, is a novel both literary and comic, with some of the crude, freewheeling madness of the kitchen still there in spirit. It is breathless and brash; it moves in strange and irregular patterns. And I think these are necessary qualities for this strange and compelling world, this court of violence and debauchery where food enjoys a kingly status. Proust would be spinning in his grave at all the drinking and drug-taking and wholesale sinning, but I believe the book is true to its own brutal, frantic sensibilities. This is a novel about chefs and the kitchens in which they labour. Here the madeleines are served on a cleaver, with a dusting of suspicious white powder.

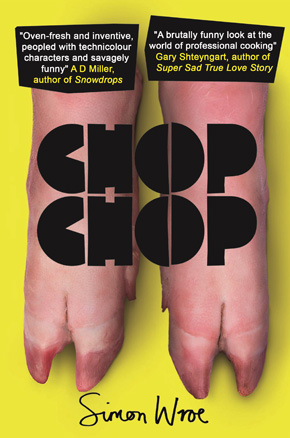

Simon Wroe writes about food and culture for Prospect and the Economist, and regularly contributes to publications including The Times, Guardian, Telegraph and Evening Standard. His first novel Chop, Chop is published by Viking in hardback and eBook. Read more.