Claire Fuller: The female gaze

by Karin Salvalaggio

“Fuller creates an atmosphere of simmering menace with all the assurance of a latter-day Daphne du Maurier.” The Times

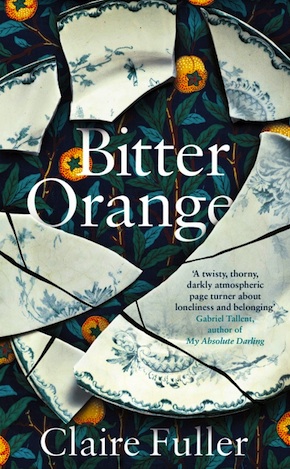

Claire Fuller’s third novel Bitter Orange is a delicious read that lingers in the reader’s subconscious long after the final page is turned. It’s the summer of 1969 and Frances, Peter and Cara are camping out at Lyntons, a once-grand, neoclassical mansion that they’re surveying for its new American owner. Frances is a socially awkward woman, who appears to have stepped right out of the 1950s. Charmed from the outset, she can’t resist the chaotic allure of Cara and Peter’s bohemian lifestyle. Cara is a young Irishwoman with a passionate nature and a locker full of fanciful stories, which she doles out to Frances like sweets. Meanwhile Peter is a flirt with a carefree nature who’s only interested in good wine, women and beautiful objects. But not all is as it appears. As their individual histories unravel they start to turn against each other with devastating results.

Bitter Orange is a book rich in metaphor and imagery. Claire’s observations of human frailty and our constant need for reinvention are beautifully observed. The dynamics she creates between characters, and between characters and setting, are wonderful. And I might as well add that her writing is sublime. I’ve spoken to Claire about her work on many occasions, but this is the first time I’ve had the pleasure of interviewing her.

KS: Your character Cara Calace bears a remarkable resemblance to Merricat Blackwood, the delightfully unreliable narrator in Shirley Jackson’s We’ve Always Lived in the Castle. Like Merricat, Cara is a fantasist who grows up in a mansion partially destroyed by a fire set by a mob of local villagers. Both women are highly strung, incredibly superstitious and strangely compelling. Interestingly, Bitter Orange’s narrator Frances Jellico is very much like Eleanor Vance from another Shirley Jackson classic, The Haunting of Hill House. The two socially awkward women have both recently lost their mothers after spending years as their carers. In what may well be a masterstroke of metafiction, Bitter Orange appears to bring Cara (Merricat) and Frances (Eleanor) together in a setting not unlike Hill House, and the dynamic is explosive. Did you realise there were such strong parallels between the characters in Bitter Orange and those created by Shirley Jackson over fifty years ago? What do you suppose it is about Shirley Jackson’s writing that has made her so influential?

CF: I had no conscious idea that there were these parallels until you pointed it out. However, I do love both those Shirley Jackson novels, and have read them several times, and I’m flattered by the comparison. I’m sure books I love seep into the novels I write, how could they not? (The only deliberate time this happened in Bitter Orange is a scene when Frances is in a London hotel, which was directly inspired by Good Morning, Midnight by Jean Rhys.) When I’m writing, the only reader I’m thinking about is myself, and I’m trying to write a novel that I would like to read. It might seem like this is what every author sets out to do, but I know for some this isn’t always the case.

Having been a reader for so long, for many years before I was a writer, I know what I like to read – that’s not to say I don’t sometimes like to be tipped out of my comfort zone – and Shirley Jackson provides those things in spades. She writes compelling stories full of fascinating and odd characters. The sense of place she creates is brilliant. And the pacing in the two novels mentioned is wonderful. You have to keep reading – but she also is able to zoom in on the details that make a character and a location completely real.

I wanted to leave the interpretation of these events up to the reader – depending on how much they lean towards liking or believing in the otherworldly.”

Though Lyntons hints at being haunted, and indeed Frances senses the presence of her dead mother on several occasions, the narrative keeps the reader guessing as to whether the incidents are down to the supernatural or simply tricks of a troubled mind. There are plenty of disturbing elements, which add to the uncertainty: the indented pillow in the bath with a long grey hair attached; the plucked-out eyes of peacocks; the statues with punched-out hearts in the mausoleum; the Judas Hole, to name but a few. Cara’s superstitious nature compounds the building tension. She winds up the suggestable Frances, putting doubts into her head as to what is real and what is imagined. Meanwhile, Frances still feels her mother’s judgemental presence and angry pinches. Were you aware of how fine a line you were treading throughout the novel? What methods to you employ to maintain it? And lastly, Lyntons seems to be too well drawn to be a figment of your imagination. Was it based on a real location?

I was very careful about the line between the supernatural and odd things that had some basis in reality. I wanted to leave the interpretation of these events up to the reader – depending on how much they lean towards liking or believing otherworldly events in fiction. All the things that the characters in Bitter Orange see or hear could have a completely plausible explanation – which I often made sure was provided by the down-to-earth Peter. Frances is very easily swayed by those around her, so she swings between Cara’s superstitious beliefs – whether this is about white cows, birds in houses, or throwing salt over her shoulder – and Peter’s rational explanations. I also had Frances touch her mother’s locket that she wears every time something odd happens; a kind of warning to those readers who spot this action.

Lyntons is based on a real location. Mostly it’s The Grange, a neo-classical house managed by English Heritage near where I live. The inside is derelict but kept in a kind of stasis, and is very atmospheric. There is a lake fed by a stream, and a very small flint grotto, but unfortunately no other follies or a Palladian bridge.

Bitter Orange is set in 1969, two years on from the Summer of Love. While some in Britain willingly embraced this more turbulent cultural age, there were signs of resistance everywhere. Frances arrives at Lyntons bearing a strict moral code and a suitcase packed with her mother’s tight-fitting undergarments and an evening dress thirty years out of date. Meanwhile, Peter and Cara are living a bohemian lifestyle. He’s dressed in flares while she goes braless and wears string bikinis. They are unmarried, seemingly modern, and overtly sexual, yet things are not all as they seem. Cara is a devout Catholic who firmly believes in the virgin birth, and we eventually learn that their relationship is sexless. Then there’s Victor the vicar, a long-haired man who openly questions his faith and wears tie-dye shirts under his vestments. Themes surrounding cultural upheaval are evocative and from Frances’ naïve perspective, a rich seam ripe for misinterpretation. I’m sure the timing the novel was purposeful given how the narrative plays out. Without giving too much away, can you expand on why you set Bitter Orange at this time?

There was a pretty mundane, logical reason in the first place for setting the novel in 1969: the characters find some things that have been hidden since the Second World War, and to make them remain hidden for much longer than thirty years would have stretched credibility. But once I’d decided on 1969, it seemed so perfect. Frances is a product of an earlier age, she still lives and behaves as if it is 1949. I wanted to show that for a lot of people that change in culture passed them by, but I also wanted that era to help with a superficial contrast between Frances and Cara. But scratch a little deeper and the reader will see that Cara still holds on to many traditional beliefs – her Catholicism, as you say, and the fact that for a long while she has felt the need to wear a wedding ring even though she isn’t married.

According to the Oxford Dictionary ‘the male gaze’ is ‘the perspective of a notionally typical heterosexual man considered as embodied in the audience or intended audience for films and other visual media, characterised by a tendency to objectify or sexualise women’. The male point of view is so prevalent that we no longer notice it. In Bitter Orange you turn this dogma on its head and give us the female gaze through the somewhat warped perspective of Frances. She secretly spies on Peter through the Judas Hole she’s found in the floor of her bathroom, taking in his most intimate moments. She feels shame but cannot turn away. She also has a notable encounter with Victor the vicar. She stares and gawps as he disrobes from his vestments as they stand in close proximity in the vestry of the village church. In another scene, she watches Peter remove his clothes as they stand on the bridge. He is only wearing swimming trunks. Her gaze lingers: “His body was spare, narrow hips and broad at the shoulders. Tufts of light hair stuck out from his armpits and a little covered his chest.” There is also a disturbing meeting with a fellow lodger in the hallway outside Frances’ London hotel room: “The white dressing gown he was wearing hung from his bony frame and was untied, open at the front. I could see what he wanted.” What inspired you to write about the female gaze and where did you come up with the idea of using the Judas Hole as a device?

I tried to show Frances looking at these characters as people, not just as bodies, even if something slightly sexual is going on.”

The spyhole in Frances’ floor with a view into Cara’s and Peter’s bathroom below was the thing that started off the whole novel. I wrote a piece of flash fiction about a man looking through a hole in a ceiling rose at a woman in the flat below. But immediately after I’d written it, I thought it would be much more interesting to have a woman doing the spying on a man. So it was this action that came first, before the idea of the female gaze. In all of the scenes you mention (and one other when Frances looks at Cara who is undressing her), I tried to show Frances looking at these characters as people, not just as bodies, even if something slightly sexual is going on. She sometimes misunderstands what she is seeing or is embarrassed by it, intrigued, curious, but she is never just looking at another person’s body for her own pleasure, which is how I often read – or perhaps more often view – the male gaze.

Though your novels could never be labelled police procedurals, they share characteristics with crime fiction or suspense thrillers, as well as gothic horror. Your first novel Our Endless Numbered Days is about a young woman kidnapped by her father and forced to live out his dystopian fantasy in the wilderness. In Swimming Lessons a woman disappears, assumed drowned, only to briefly reappear across the road from a bookstore her husband frequents. Bitter Orange is set in a house that evokes a sense of dread and has all the hallmarks of literary suspense. There is crime and punishment and just enough resolution. In the closing chapters of a typical crime novel, there is an expectation that the reader will be given all the information they need so they can re-enter the world knowing that order has once again been achieved. It is a device that leaves very little room for conjecture. In literary novels, readers are left to connect at least some of the dots for themselves, a hallmark I’d like to see more of in mainstream crime novels. Could you remark on the differences and similarities between traditional crime novels and literary fiction? Have any ‘mainstream’ crime novels inspired you? Which literary suspense novels do you recommend?

I do enjoy novels that cross the boundary between literary and crime. However, what I find in many contemporary crime novels is that the plot and the pace is created at the expense of the writing. When I read, I want sentences that have been crafted: maybe crafted to make the reader turn the pages faster to find out what happens, but definitely a great deal of editing will need to have been done for me to enjoy it. The novels that do this well are ones I’d want to re-read in order to find more depth; something that is sometimes missing from crime fiction. You’re right that another thing that is absent in crime is ambiguity: readers of crime would definitely be frustrated if they didn’t find out ‘who did it’ by the end (unless there’s a sequel). I would also say that crime fiction is generally plot-driven, while literary fiction isn’t. Similarities of course could be all manner of things: a crime for a start, a fast pace, great writing. Donna Tartt’s The Secret History is one of my favourite novels with a crime at its centre, but it’s also literary, in that the writing is very fine. Others that make that crossover in some way would include The Lie of the Land by Amanda Craig, Apple Tree Yard by Louise Doughty, Idaho by Emily Ruskovich, and Tony and Susan by Austin Wright. All of which I’d highly recommend.

Claire Fuller was born in Oxfordshire in 1967. She gained a degree in sculpture from Winchester School of Art, went on to have a long career in marketing, and didn’t start writing until she was forty. She has an MA in Creative and Critical Writing from the University of Winchester and lives in Hampshire with her husband and two children. Her first novel Our Endless Numbered Days won the Desmond Elliott Prize and was a 2016 Richard and Judy Book Club pick. Her second, Swimming Lessons, was shortlisted for the Royal Society of Literature’s 2018 Encore Award. Bitter Orange is published by Fig Tree/Penguin in hardback, eBook and audio download.

Claire Fuller was born in Oxfordshire in 1967. She gained a degree in sculpture from Winchester School of Art, went on to have a long career in marketing, and didn’t start writing until she was forty. She has an MA in Creative and Critical Writing from the University of Winchester and lives in Hampshire with her husband and two children. Her first novel Our Endless Numbered Days won the Desmond Elliott Prize and was a 2016 Richard and Judy Book Club pick. Her second, Swimming Lessons, was shortlisted for the Royal Society of Literature’s 2018 Encore Award. Bitter Orange is published by Fig Tree/Penguin in hardback, eBook and audio download.

Read more

clairefuller.co.uk

@ClaireFuller2

Author portrait © Adrian Harvey

Karin Salvalaggio is the author of the Macy Greeley crime novels Bone Dust White, Burnt River, Walleye Junction and Silent Rain and a contributing editor at Bookanista. Her fiction to date is set in towns that border the Montana wilderness, a uniquely spectacular landscape she fell in love with as a child. Her proudly independent characters inhabit stories about the American dream gone wrong. She is currently working on the final edits of a psychological thriller set closer to home in West London, where she has lived since 1994. The characters may be hemmed in by glass and steel, but the stories they tell are just as compelling.

Karin Salvalaggio is the author of the Macy Greeley crime novels Bone Dust White, Burnt River, Walleye Junction and Silent Rain and a contributing editor at Bookanista. Her fiction to date is set in towns that border the Montana wilderness, a uniquely spectacular landscape she fell in love with as a child. Her proudly independent characters inhabit stories about the American dream gone wrong. She is currently working on the final edits of a psychological thriller set closer to home in West London, where she has lived since 1994. The characters may be hemmed in by glass and steel, but the stories they tell are just as compelling.

karinsalvalaggio.com

@KarinSalvala