Climbing without a rope

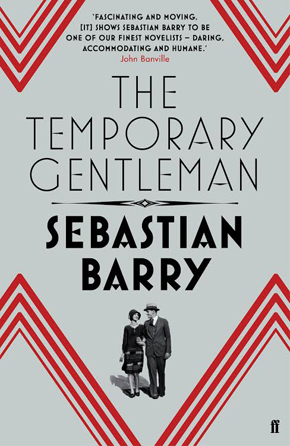

by Sebastian BarryThe ‘temporary gentleman’ in the title of Sebastian Barry’s latest novel is an Irishman commissioned into the British Army during the Second World War who looks back on past demons and a tumultuous marriage to the enigmatic beauty who slipped from his grasp. Here’s a slice of his writing day.

Where are you now?

At home – an old rectory beside a tiny hamlet in the Wicklow mountains, inside this perpetual rain.

Where and when do you do most of your writing?

In this small room, where once the rectors wrote their sermons. I work throughout the day, coming in and out, sneaking up on things, trying to catch another paragraph by surprise.

If you have one, what is your pre-writing ritual?

Idleness, both wonderful and fretful, followed by a check to see everything is in its place, that the laptop is aligned with the centre of the desk, and also the chair, then I think of the sort of relaxed concentration a player might find useful at Wimbledon, and hopefully…

Full-time or part-time?

Full-time since I left Trinity College Dublin in 1977 – don’t ask me how I managed it for the first fifteen years. Mysteriously.

Pen or keyboard?

Keyboard, eventually printout, then the black-ink Schaeffer pen I bought in Iowa City in 1984 for corrections and additions – my first computer was given to me by my friend David Berber, because he thought I was mad doing all that retyping. A lovely man, who died recently.

How do you relax when you’re writing?

Well, I think it is important to relax in the very act of writing, as per the mention of Wimbledon above. Between bouts though, running 4 miles every second day is essential, though sometimes this gets regrettably neglected. But equally there can be such a sense of being ‘on the hunt’, day and night, that relaxing isn’t possible – maybe not desirable. Going out and being a normal human being doesn’t help much either, I find.

How would you pitch your latest book in up to 25 words?

Lower-class Sligoman with hankering after respectability marries marvellous middle-class girl in the twenties, and all goes downhill from there.

Who do you write for?

I write firstly for my characters, to give them something to do in the afterlife that is a book, and then for those souls I will most likely never meet, those who find the book poses the question for which they already had the answer, miraculously.

Who do you share your work in progress with?

With my benign and all-seeing editors at Faber and Penguin, and my agent Derek Johns, but usually only the first few chapters, because they can take as much as a year to get done, with the rest of the book following more quickly. At a certain point you need to hear a few cheering remarks. I often think of sending things, toy with the idea, but more usually let it drop. Some of the climb is best done alone, without a rope.

Which literary character do you wish you created?

Thousands – but King Lear, since you put no limit on it.

Share with us your favourite line/s of dialogue, poetry or prose.

“The oldest hath borne most. We that are young

Shall never see so much nor live so long.”

William Shakespeare, King Lear

Which book do you wish you’d written?

Nostromo by Joseph Conrad. To me it is the supreme novel in the English language, even more so because before he began it he thought he had nothing left to write about.

Which book/s have you most recently read and enjoyed?

Pagan Britain by Ronald Hutton. Truly a gripping read, an astonishing account of early origins, as thrilling as any thriller. Also a book by the magus of the memoir Hugo Hamilton, called Every Single Minute.

What’s on your bedside table or e-reader?

I have an early edition of Heart of Darkness by Joseph Conrad, published by Dent in the twenties, which I was rereading in order to write an introduction to a new edition. I don’t have an e-reader.

Which books do you feel you ought to have read but haven’t yet?

All the brilliant novels I get sent in proof. I do read as many as I can, sometimes to send a grateful letter back to their editors, and sometimes to try and steal the things each novelist uniquely knows.

Which book/s do you treasure the most?

Two poetry pamphlets that Harold Pinter sent me, and also two beautiful special editions of the two novels of mine that were shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize.

What is the last work you read in translation?

A glorious, hard and atrociously poignant book by the French writer Jerome Ferrari, entitled Where I Left My Soul, that helped me so much in the writing of a new novel.

Which story collections would you particularly recommend?

The two by Claire Keegan, Colm Tóibín’s The Empty Family, the eternal two by Kevin Barry – and single stories, ‘Fishing the Slow-Black River’ by Colum McCann, and ‘The Last of Deeds’ by Eoin McNamee, both just two or three pages long.

What will you read next?

Native American Testimony by Peter Nabokov (published in the USA by Penguin).

What are you working on next?

I have to write a short speech for a conferring in April. Very difficult!

Imagine you’re the host of a literary supper, who would your dinner guests be (living or dead, real or fictional)?

Horace, Seamus Heaney, Bob Stine, Catullus, Sir Thomas Browne, Donal McCann (a highly literary actor), Elizabeth Taylor (the novelist, not the actor), and King Lear.

If you weren’t writing you’d be…?

House building – an altogether more tangible undertaking.

Sebastian Barry was born in Dublin in 1955. His plays include Boss Grady’s Boys (1988), The Steward of Christendom (1995), Our Lady of Sligo (1998), The Pride of Parnell Street (2007), Tales of Ballycumber (2009) and Andersen’s English (2010). His novels include The Whereabouts of Eneas McNulty (1998), Annie Dunne (2002), A Long Long Way (2005), The Secret Scripture (2008), On Canaan’s Side (2011 and The Temporary Gentleman (2014), all published by Faber and Faber.

He has won, among other awards, the Irish-America Fund Literary Award, the Christopher Ewart-Biggs Prize, the London Critics’ Circle Award and the Kerry Group Irish Fiction Prize.

Read more.