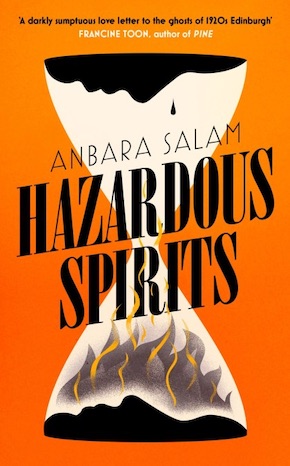

Connecting with lost souls

by Anbara Salam

My third novel Hazardous Spirits is set in Edinburgh in 1923. The story follows Evelyn Hazard, whose husband Robert wakes up one day and announces that he can speak to the spirits of the dead. Like many strange tales, the idea for this novel originated during an unusual blind date. I arrived late to the pub to find my date already there, a tall, striking and very charismatic woman. As the evening progressed, I discovered that we had a great deal of overlapping interests, mutual friends, and also that she worked part-time as a psychic medium. When I was at school, we’d made our own crudely-drawn Ouija boards in the classroom and turned off the lights at lunchbreak to contact the spirits – on one memorable occasion a gust of wind slammed the door shut and we all entered a tailspin of panic. But this was the first time that I’d ever met someone who was not only convinced that spirits existed, but had made it their job to convince other people as well.

The origins of Spiritualism are often traced to 1848 in upstate New York when sisters Margaretta and Catherine Fox drew attention to a repeated knocking and tapping sound in their farmhouse. They insisted that the sounds were produced by a disembodied spirit, and that they could interpret and channel these messages. As the women showcased their skills in public demonstrations, a movement began to galvanise around the belief that the human spirit survives beyond death, and that individuals with a honed ability to contact them could reach across the veil separating mortality from eternal existence. The Spiritualist movement eventually became an association of churches in the US in the 1890s, and this blend of religious conviction and mystical healing proved something of a phenomenon, particularly in the early years following the First World War.

The events of Hazardous Spirits take place in 1923, against this backdrop of increased Spiritualist popularity. In the United Kingdom, WWI claimed the lives of 6 per cent of the adult male population, and the influenza pandemic of 1918–20 killed around 230,000 further people, largely affecting those under 30 years old. This gross national and global trauma provoked a search for answers beyond those offered by traditional belief systems, and people across social classes sought comfort from their grief in the promises of Spiritualist mediums. In Hazardous Spirits, Evelyn finds herself drawn into an unfamiliar society of aristocrats, ex-soldiers and eccentrics by virtue of her husband’s participation in the Spiritualist movement in Edinburgh.

Scotland has a long and complex reputation as a ghostly country. Partly this myth-making of Scotland as a haunted nation developed along with the mapping of a late 18th-century interest in Gothic literature and architecture onto the majestic landscape of Scotland’s ruined castles, misty forests and crumbling bothies. In some cases, the Scottish talent for the uncanny speaks for itself. For example, the decision in the 1760s to simply pave over parts of central Edinburgh and rebuild on top of the existing buildings, leaving some residents and businesses to continue to trade from claustrophobic subterranean passages.

Over the course of at least two years writing the novel, I asked absolutely everybody I met if they believed in ghosts, with some surprising results.”

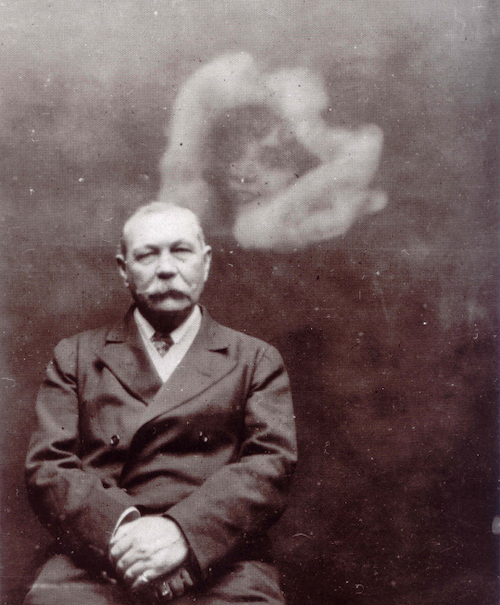

Some of the most influential Spiritualist practitioners and advocates of their time were Scottish. Edinburgh-born Daniel Dunglas Home (1833–86) was one of the most well-known mediums in both Europe and America. As a young man, Home and his family emigrated to Connecticut, where he found eminent success as a medium before returning to Europe for his health, touring among members of various European royal families. Among his mediumistic skills, Home also claimed powers of levitation and telekinesis. Home became something of an international talking-point, drawing reproach from public figures such as Harry Houdini while being supported by another famous Scotsman at the forefront of Spiritualism, Arthur Conan Doyle. Doyle (1859–1930) was a medical doctor and leading writer of the period, most well-known of course as the creator of the Sherlock Holmes stories. In the late 1880s, Doyle became more involved in Spiritualist circles, eventually becoming President of the London Spiritualist Alliance, and President of the British College of Psychic Science.

Interestingly Edinburgh itself was, however, not an especially welcoming place for the early Spiritualist movement, which found greater popularity in Glasgow in its nascent years in the UK. Priding itself as a seat of learning and reason, Edinburgh society was largely resistant to public demonstrations of Spiritualism, with the Edinburgh Society of Spiritualists not developing until a good sixty years after the founding of the Glasgow equivalent. It was this context of conflicting worldviews that drew me to explore the plot of Hazardous Spirits in Edinburgh. In the tug of war between sense and sensibility, Evelyn finds herself moving continually from belief to scepticism and back again, battling with her own desire for life to return to ‘normal’ as it had been before the war, and at the same time nursing hope for the alluring promises of new horizons.

Researching just such promises took me to some odd places. During one such rabbit-hole into Spiritualist merchandise, a friend purchased for me a ‘spirit doll’, purportedly haunted by the ghost of a deceased 1970s feminist. I was instructed by the letter sent by its procurer that the spirit inhabiting the doll could be contacted by use of a special pendulum, and that she particularly enjoyed looking out of windows. I didn’t believe a word of it. And yet the doll is currently at my window as I type, dutifully placed where it can see into my front garden. As Edith Wharton wrote, I don’t believe in ghosts, but I’m afraid of them.

With these sessions functioning for free, or for a nominal contribution, who wouldn’t be willing to suspend disbelief that they were contacting a lost loved one, for less than the price of a cup of coffee?”

Over the course of at least two years writing the novel, I asked absolutely everybody I met if they believed in ghosts, with some surprising results. A politically conservative and devout Christian acquaintance casually told me that the spirit of their late husband visited them frequently. During the pandemic, Spiritualist churches and associations began to host online seances, and I attended regular services as a silent observer. What struck me during these sessions was the hopefulness and positivity of the gatherings, and not the grief of the attendees as I had expected. This hope manifested in perhaps an over-eagerness to interpret the pronouncements of the mediums leading the session, to find meaning where it may seem loose, or at least fuzzy, to a non-invested observer. To borrow historian Richard Landes’ term, this kind of ‘semiotic arousal’ is not unusual for communities already primed to read for patterns that confirm an existing worldview. In the context of a seance, it might be something like a medium announcing they had made contact with a spirit who enjoyed music, or was fond of animals, to prompt a volley of recognition from attendees. And yet with these sessions functioning for free, or for a nominal contribution, who wouldn’t be willing to suspend disbelief that they were contacting a lost loved one, for less than the price of a cup of coffee?

As my time attending seances continued I became aware that, despite attending from a place of research and observation, I was not immune to the transportative promises of such sessions. While not a believer, I found the relief and comfort provided to the bereaved very moving, and in the wake of a bereavement in my own life, I became aware of a faint yet twinkling hope that I too might discover convincing evidence for life beyond mortal death. In the final months of writing Hazardous Spirits, I booked a one-on-one session with a medium. Some of the details she provided made little sense to me, some struck very close. But the medium interrupted herself at one point, and asked me if I considered myself spiritual. I stuttered, not having a ready answer for this question, but she interrupted herself again, to deliver me an alarming prophecy: one day I would have a direct encounter with a ghost. “Be very careful what you wish for,” she advised, and even through my scepticism, I found her words chilling. I left the session almost disappointed that my worldview had not been transformed by a life-altering perspective shift. But in the following months as I was roused again and again in the night by my young baby, I would find myself awake in the wee hours, looking out onto the dark corridor at the top of the stairs, hear the voice of the medium coming back to me, and think: maybe now?

—

Anbara Salam is half-Palestinian and half-Scottish and grew up in London. She has a PhD in Theology and now lives and works in Oxford. Her previous novels are Things Bright and Beautiful (Fig Tree/Penguin, 2018) and Belladonna (Fig Tree/Penguin, 2020). Hazardous Spirits is published by Baskerville/John Murray in hardback, eBook and audio download.

Read more

anbarasalam.com

@anbara_salam

@BaskervilleJMP

@johnmurrays