The sparks of an obsession

by Sunny Singh

I WAS EIGHT WHEN I REALISED that stories were not simply magic; that they didn’t arrive into the world already formed. Like puppies or babies or films.

Two months before that birthday, the very first non-Congress government had swept to power in India, and with it, the end of the Emergency which had suspended civil rights for nearly two years. The new government struggled to balance the many domestic and international demands, but I remember that our home seemed oddly lighter that spring. I remember that Coca Cola was ‘thrown out’, a term I did not understand except that the beverage disappeared as the occasional treat. By the summer holidays – and my birthday – debates around our dinner table had grown more heated. I remember only a few of these but they all featured the ‘Shah Commission’. Justice Shah was a hero or a villain depending on who was arguing. That was when I first learned that a point of view can change the appearance of the world, that reality shifts with the one telling it.

I turned eight in 1977.

It was also a bumper year for Hindi cinema! Manmohan Desai – one of the greatest commercial filmmakers ever – released not one or two but four of his biggest hits: Amar Akbar Anthony, Chacha Bhatija (Uncle, Nephew), Dharam-Veer and Parvarish (Upbringing). From veteran directors like Nasir Hussain to auteurs like Hrishikesh Mukherjee, from the brave Doosra Aadmi (The Other Man) to the Akira Kurosawa knock-off Inkaar (The Refusal), from a formulaic Darling, Darling starring a fading Dev Anand, to Shyam Benegal’s challenging Bhumika (The Role), 1977 produced many of the films that are now touchstones of Indian, and world, cinema. Even the poet-director Gulzar, known for his careful, deliberate filmmaking despite the pressures of the commercially driven movie-churning machine, released two feature-length films, Kinara (Shore) about a grieving dancer and Kitaab (The Book) about a young boy who runs away from home.

For a film that I now know comprehensively, I have no actual memory of watching it that evening. But I know that’s when the itch was born. And it has lingered.”

I saw most of these films much later than 1977. My family practised a strict curating system based on the ‘grapevine’, or word passed down by trusted colleagues, acquaintances, family friends, most of whom were likely to be young men and ‘first day, first show’ types who would apply their own idiosyncratic classifications to the new releases: family watch, ok-for-kids, take-the-wife, fun watch for mixed gender friends, and do not watch with anyone but male friends. Growing up, I was permitted the ok-for-kids movies, although Gulzar’s Kitaab slipped through this quixotic rating system and promptly traumatised me for many years afterwards. Very occasionally, I was also allowed films deemed appropriate for the full family, which were mostly blockbusters and our own version of PG-13.

Parvarish sat in this second category. In retrospect, it seems a poor choice as it features a terrifying sequence of two young children watching their parents being violently murdered, shot entirely from the points of view of the children hidden inside a barrel. Given that my extended family had deemed me sensitive – I was prone to stress-induced asthma attacks – the choice of this film has always seemed surprisingly careless.

I remember that we occupied almost an entire a row in the balcony of the cinema hall. I sat in the centre and my aunt and cousins cocooned me from both sides. My uncles sat in the seats closer to the aisles. Friends and acquaintances sat in the rows behind and before us. Even in the darkened cavernous hall, I felt coddled, comforted and safe. One of the adults brought us super salty popcorn and odd-tasting Thums-Up, the indigenous replacement of Coca Cola that had recently hit the market.

Afterwards, as we made our way home on a cycle rickshaw, my cheeks were chilled by the winter breeze coming off the Ganga and I snuggled into the warmth of my aunt’s arms. My uncle raced ahead on his motorcycle and then back again to check on us, like a one-man guard of honour. And I remember the comfort of my grandmother’s breathing next to me when my nightmares woke me late that night, and on many nights after.

For a film that I now know comprehensively, I have no actual memory of watching it that evening. But I know that’s when the itch was born. And it has lingered. Most of all, I remember the sick feeling in my stomach that told me that something was being kept from me. Like so much else – terrible or glorious – that the adults withheld from me, there was something special about films, about those stories on the vast white screen. I was sure that once I learned the secret, and only then, I would be a master, a magician, a secret bearer. And then I would be grown up.

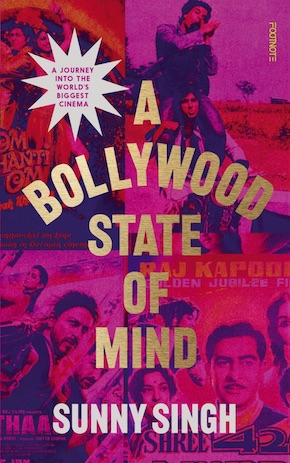

from A Bollywood State of Mind (Footnote Press, £20)

—

Sunny Singh is a writer, novelist, academic, and champion for decolonisation and inclusion across all aspects of society. Born in Varanasi, India, she read English and American Literature at Brandeis University in the USA before gaining a Masters in Spanish Literature from Jawaharlal Nehru University, Delhi and a PhD from the Universitat de Barcelona. She lives in London where she is Professor of Creative Writing and Inclusion in the Arts at the London Metropolitan University. She is the author of the novels Nani’s Book of Suicides, With Krishna’s Eyes and Hotel Arcadia and a study of Amitabh Bachchan for the BFI’s Film Stars series. In 2017 she launched the celebrated Jhalak Prize for literature by writers of colour. A Bollywood State of Mind is published in hardback and eBook by Footnote Press.

Read more

sunnysingh.net

@ProfSunnySingh

@WeAreFootnote