Liminal spaces and impossible things

by Menna van Praag

I’ve been obsessed with and seduced by the notion of liminal space since childhood. It began with The Chronicles of Narnia. As an eight-year-old I devoured The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe and, long after the story started to fade the obsession with wardrobes remained. My paternal grandmother lived in a large, spooky Victorian terraced house in Yorkshire and in the bedroom where my brother and I slept stood a vast wooden wardrobe. I was convinced that this epic piece of furniture was the portal to the land of Narnia. Every summer, every Christmas, every Easter, I heaved open its heavy doors, whispered an incantation of hope, closed my eyes, reached behind the coats and waited for my fingertips to be brushed with the chill of snowflakes. I was eight when I stopped believing in Father Christmas but didn’t stop believing in Narnia ‘til I was at least sixteen.

Okay, you’ve caught me, I believe it still. And that’s why I write fantasy stories; because I want to keep believing in magic. The world might appear mundane, it might be frequently full of disappointment and despair, but it continues to contain marvels and mysteries which, frankly, is what makes the misery bearable and life worthwhile. While I write I’m living in that liminal space, floating in that glorious bubble between reality and fiction: the space of inspiration and imagination. It is my comfort zone, my safety, the place I most love to be. Perhaps all writers feel this way, no matter what they write, I do not know. I will start asking them.

Narnia continues to exert its influence on my imagination; lingering in the shadows of my memory, remaining in the background (or coming to the foreground, depending on whether I am writing magical realism or fantasy) to open the doors of my mind to other liminal spaces, other worlds… The Sisters Grimm trilogy is my homage to Narnia, the gates that lead the sisters to Everwhere are my nod to the wardrobes I loved so much, with a particularly Cambridge and Oxford spin. I grew up in Cambridge but went to Oxford and all my life I’ve been entranced by these ornate gates scattered about the town and the colleges, all guarding the entrances to places mere mortals are not permitted to go. Usually, they are accompanied by a plaque declaring: “Master’s Garden: Private”. Which, as anyone knows, only makes the forbidden garden all the more alluring. So, since I couldn’t enter them in reality I decided to do the next best thing and enter them through the liminal space of my own imagination and inhabit these secret, private, forbidden spaces in fiction. Then, of course, my writerly imagination took on its flights of fancy and the garden became a forest and the forest became a twilight land, with “ancient trees stretching to the marbled sky and an infinite network of roots reaching out to the edge of eternity.” Which was how I first discovered the realm of Everwhere and led my characters there.

One of my favourite literary quotations is in Through the Looking-Glass, when the White Queen declares: “Why, sometimes I’ve believed as many as six impossible things before breakfast.”

Around the same time I discovered Narnia, I tumbled into Wonderland. Now I must admit that I wasn’t especially bewitched by the world of Wonderland itself – the Red Queen terrified me and the Mad Hatter unnerved me – but I was utterly enchanted by both the aesthetic of the place (never-ending tea parties in particular) and the notion of falling down a rabbit hole and into another land. In my youth, living mainly in the city of Cambridge, I didn’t encounter nearly as many rabbit holes as I did wardrobes, but when we went walking in the moors of Yorkshire I delighted in encounters with rabbits and always followed them till they hopped out of sight. The reason why I love reading fantastical fiction is akin to the reason why I love writing it; because it illuminates the ‘ordinary’ world with a silver-edged glow, as if being viewed on a magical, moonlit night, rendering everything enchanting. And not simply that, but also inspiring. One of my favourite literary quotations is in Through the Looking-Glass, when the White Queen responds to Alice’s declaration that one cannot believe in impossible things by retorting: “When I was younger, I always did it for half an hour a day. Why, sometimes I’ve believed as many as six impossible things before breakfast.” Surely words to live by. And arguably the first thing you must believe in is yourself.

It was at school that I first discovered the wonderment that was A Midsummer Night’s Dream and it remains my favourite Shakespeare play, the one I’ve seen in so many iterations that I lose count. I say this a little shamefully, since it’s such an easy, effortless engagement with something so fun and fantastical; but then again I find an unashamedly therapeutic uplift in fiction, a necessary balm to the pains of reality, and would be unable to exist on a restrictive diet of tragedies, of Hamlet and King Lear, without the escapism offered by the comic and, most of all, the fantasy.

The books we read as adults rarely have the same impact on us as those we read as children, but I have three fantastical exceptions to that general rule: Stardust, The Girl Who Drank the Moon and The Night Circus. All of these, to a greater or lesser degree, occupy the realm of liminal space – Gaiman’s wardrobe door has become a wall, Barnhill has the woods and Morgenstern the circus tents – and thus I read each of these novels every year simply in order to step through these portals and into their magical worlds. And there I will happily stay – as I will in my own self-created worlds – until I am unceremoniously pulled away by the necessity of making dinner or answering an email or writing an article such as this. Now, if you’ll please excuse me, it’s time to leave you and return to Everwhere.

—

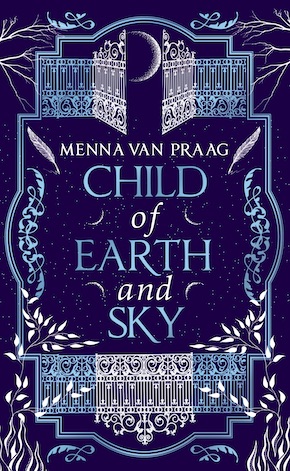

Menna van Praag is a creative writing tutor at Cambridge University, a freelance book editor and has worked as a reader for BBC Films and TV and as a script editor for a number of independent production companies. She is the author of seven magical realism novels, including The House at the End of Hope Street, which have been translated into 26 languages. The acclaimed The Sisters Grimm (2020) marked her first foray into dark, contemporary fantasy, and was followed by Night of Demons and Saints (2022). Child of Earth and Sky, the final book in the trilogy, is published by Bantam/Transworld Digital in hardback and eBook.

Read more

mennavanpraag.com

@MennavanPraag

@TransworldBooks

@bantambooksuk

Author photo by Rafal Lapszanski