A summer night

by Michal AjvazI WAS APPROACHING ST. VITUS CATHEDRAL from the Old Castle Stairs. Night had fallen, and the first stars were appearing in a clear sky. The chancel – a black silhouette of columns, flying buttresses and pinnacles – rose before me. The castle’s courtyard opened up to my left. The place was deserted and so quiet, I could hear the water falling in its gentle arc from the mouth of the fountain’s metal monster into its shallow basin.

I headed for the dark opening of a lane called Vikářská that winds along the right-hand side of the cathedral. As I stepped into the cathedral’s shadow, from the impenetrable darkness behind a column, something jumped out at me. I caught a glimpse of a bulky and rather squat mass and heard a thump, as if a hard, inanimate object had landed on the cobbles. What followed was a sound like the sharp snapping of jaws which sent a chill down my spine, and I inadvertently let out a cry. The fabric of my trousers was gripped at the knee, caught in something’s terrible maw. Instinctively I pulled my leg free and jumped to the side. Peering into the darkness of the lane, I tried to make out what kind of creature had leapt out at me.

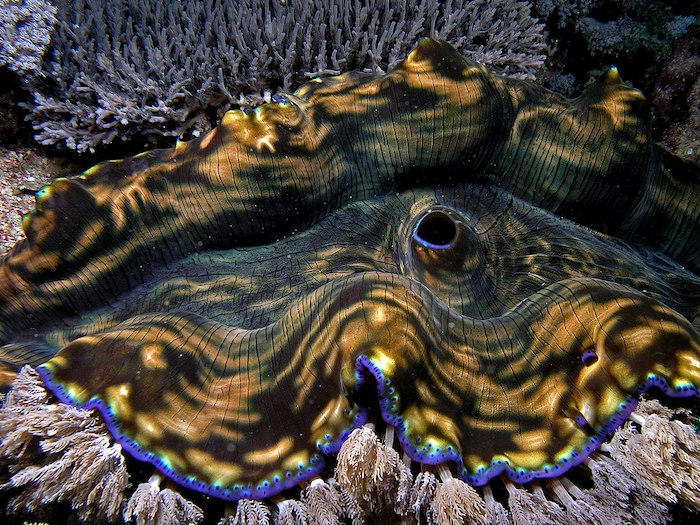

There, on the cobblestones was a clam about eight feet long, still gently rocking on the curve of its lower valve from the impact of its fall. Now it was cautiously opening again. I do not believe that clams have eyes, but this one gave the appearance of watching me through its slit. A brawny leg slid out over the edge of the lower valve, touched the pavement, and with it the creature pulled towards me slightly. Then the leg retracted, but the shell remained open, as though the creature were waiting for something. It occurred to me to lure the clam to my home, where I would place a billiard ball inside it, feed it and wait for the ball to be coated with mother-of-pearl. In my studio flat, life with a clam longer than I was tall, and an undomesticated one at that, would be far from pleasant. But if it were to present me with the largest pearl in the world, wouldn’t a few weeks of discomfort be a price worth paying? Besides, perhaps the clam could be tamed. I pulled a bread roll from my pocket, crouched down, and carefully held out my hand to the clam. It clattered its valves so menacingly that I retreated a few yards. A low growl may have come from the half-open mouth, or the clam may have been silent. On some nearby scaffolding I saw a long, thin strip of wood. I fetched this and eased it into the clam’s black slit. In a flash, the wood snapped under pressure from the sharp edges of the valves – the kind of crunch a crocodile would’ve been proud of. The clam then opened and spat out the remains, before thrusting out the leg again and inching towards me. The edges of the valves were trembling, as though with a dark rage long nurtured on the sea floor. I quickly forgot the pearl the size of an ostrich egg.

The clam was now lying across Vikářská, making the lane impassable. If I were to try to slip around it, I knew it would snap at me again, and this time I might not be so lucky. I imagined one of my arms or legs being caught and then snapped between the valves, like that strip of wood. I turned my back on the thing and set off across the castle courtyard.

I took my time crossing the deserted courtyard, the wall of the cathedral high and sheer to my right. All the while I was aware of the monotonous, stubborn shuffle on the stones behind me.”

I’d only taken a few steps when I started to hear steady shuffling sounds behind me. Turning to look, I could see it inching towards me with its sub-aquatic gait, a movement that involved extending the leg, establishing a grip on the cobbles and pushing off. I needn’t have been alarmed: although the clam seemed to be investing all its strength in the crawl, it was very slow. I took my time crossing the deserted courtyard, the wall of the cathedral high and sheer to my right. All the while I was aware of the monotonous, stubborn shuffle on the stones behind me. The next time I looked back I was about to enter the passageway. Light from the lamps along the wall of the palace was reflected on the smooth granite at the centre of the yard, as if on the cold surface of a lake; there, a black, oval silhouette lay still. The clam was resting after its exertions, the leg dangling over the edge of the lower valve like the tongue of an exhausted dog. I felt sorry for it. I don’t know what you have against me, I thought. Maybe I deserve your hatred. When we meet on the sea floor I will be at your mercy, but here in the city your exhausting efforts are in vain and causing you needless pain. How about you and I part in peace? But once again the clam brought its leg down on the cold granite and resumed its slow and spiteful march. It was coming after me with such persistence one might have believed it had made the long journey from the bottom of the ocean for my sake only – to catch, chew on and devour me.

I arrived at Hradčany Square and descended to the stone balustrade, the lights of the city afloat below. I shall wait here for the clam to appear, I told myself. And moments later I did indeed see a sharp-angled black wedge appear in the castle gate beneath the statues of wrestling giants. The clam was edging its way out of the castle. Having moved out of the castle grounds, narrow end first, the clam stopped and used its leg to rotate. It must be looking for me, I thought. Perhaps it did have eyes inside its shell. Then again, perhaps it was sniffing the air for my scent, like a dog. It occurred to me that the clam really had stopped with its half-open visor pointed directly towards me. I couldn’t shake the sense of being watched by a pair of small, evil, hidden eyes. Once more the clam set off purposefully in my direction. The square sloped downwards so the clam was able to slide, making its progress markedly quicker. Even so, it had no hope of catching me. I was getting tired of the whole thing. With a wave to the clam, I set off down Neruda Street, heading for Malostranské Square. My thoughts turned to other things. Before long, I had forgotten all about the clam.

But when I reached the arcade of the Smiřický Palace I heard once more the strange rattling and screeching, followed by a number of thuds. I turned back and froze: the clam was careering towards me down the steep street, bouncing off the cobbles, thrown from belly to back and back again, tossed from the one kerb to the other. Finally, with an ominous boom, it dashed against the closed gate in the portal of the Thun-Hohenstein Palace and a thin section of its shell chipped off from the edge. In the light of the streetlamp, I saw the gleam of mother-of-pearl through the break. I stood as if rooted to the spot, as rigid as the baroque statues on the palace facades. A group of Japanese tourists was emerging from the beerhouse U Kocoura. The clam flew between them like a cannonball, clipping a man in a raincoat who had been facing the other way, sending him flying backwards. Still, he managed to reach into his bag for a video camera and film the receding clam. Albeit in Japanese, his enthusiastic cries made me wonder if he considered giant clams to be a Praga magica attraction for foreign tourists, much like the Golem and executions in the Old Town Square.

When at last I gathered my wits, the clam was a few yards from me. I took off across the lower part of Malostranské Square, weaving through parked cars, turning repeatedly to check on the horrifying progress of the mad creature. Behind the lit windows of cafés, the last customers of the day looked on with curiosity.

A lighted Number 12 tram arrived from the Klárov stop; I got on at the last carriage. As all the doors were closing and the tram jerked into motion, I heaved a sigh of relief. Standing at the back of the over-lit empty carriage, looking through the glass, I saw the clam fly across the lower square and strike the arcade of Malá Strana Town Hall with such force that it was tossed onto its back. There it lay pitifully opening and closing its valves as though gasping for breath. The tram turned onto Karmelitská.

I sat down on the rearmost seat and was overcome by a pleasant drowsiness. I would soon be at home under my duvet, I thought, and all the phantoms crawling in the city streets that night would be far away and of no concern. The shuddering carriage was lulling me towards sleep, and my eyelids were beginning to droop, when the tram came to an abrupt halt. Immediately I was unnerved. We were between stops, near the entrance to the Michna Palace. I rose from my seat to discover that workers were repairing the track in front of us. Impatient for the tram to start up again, I kept an anxious eye on the bend in the road beyond which Karmelitská meets Malostranské Square. The clam appeared sooner than I thought.

In all the years I’d been wandering about Prague lost in thoughts of phenomenology, surrealism, Hegel and Malá Strana dandyism, the possibility of being devoured by a clam on the night tram had never occurred to me.”

It was moving in fits and starts along the shiny track. Overcome by panic, I ran about the carriage and shook the closed doors, which refused to budge. The clam had achieved peak performance and was approaching the perfect crescendo. The smooth tracks made its progress easy. Again, the leg was extended, pushing the shell forward with machine-like regularity. It reached the back of the tram, placed its foot on the door and pushed itself upwards. Soon it was perpendicular to the ground, back up, thrusting the sharp end of its shell into the crack between the closed doors. I sat petrified on the seat nearest to them, watching the dark oval break in little by little through persistent, regular, jolts. Were these sounds the clam’s snorts of exertion, or were they made by the rubber edging on the doors? I jumped up, gripped the clam with both hands and tried with all my might to push it out of the carriage. But my strength was meagre against the furious onslaught of the clam, whose blows against the doors were ever more powerful. It was as though the clam had transformed into a huge, unstoppable hammer. I sensed that it had given in to a dark ecstasy. Its thrusts came thicker and faster; there was triumph and jubilation in the thrashing of the doors. I knew that the doors would soon give way, and that the full weight of the clam would burst inside. As soon as the clam and I were alone in the carriage, my end would come, that much was clear to me. In all the years I’d been wandering about Prague lost in thoughts of phenomenology, surrealism, Hegel and Malá Strana dandyism, I’d often asked myself: where will all this end? I’d reckoned with all kinds of things – from terrible defeats to brilliant victories – but the possibility of being devoured by a clam on the night tram had never occurred to me. All manner of strange thoughts flooded my mind. I imagined the valves of the clam closing over me, leaving me lying in a dark, slimy dampness, then hearing a deep voice saying:

‘You wanted to live with me in your one-room apartment. Now we will be inseparable. We can chat whenever we want or have deep conversations about philosophy. You can rest in a bed softer than those princes sleep in. I will give you pearls to play with. I will describe all the landscapes we travel through. In your benevolent darkness, you will see them in your mind’s eye, in images more beautiful than the reality. You will never be troubled by snow or rain or a disagreeable wind…’

‘No, no, you’re very kind, my dear clam,’ I’d reply. ‘And I’m grateful for the offer, but wind and snow are no trouble to me, you see I’m used to them. I have business to attend to here, so I’d prefer to stay outside.’

‘How ungrateful and impudent you are! If this is how matters stand, I will bite off your head, keep it and cover it slowly with mother-of-pearl, so making a masterpiece, the largest, most magnificent pearl in the world…’

At this point, the clam was two-thirds into the carriage. By the time the tram jerked back into motion, I had given up my futile pushing and was sitting resigned by the door. The clam was sticking out like a huge extendable indicator. It swayed helplessly for a while before falling away just as the tram was overtaken by a taxi. The taxi slammed into the clam and tossed it onto the pavement, where it upset several dustbins, which then clattered across the cobbles, spilling empty bottles, crumpled cardboard boxes and rotten apples as they went.

On reaching home I went straight to bed, where I fell asleep immediately. A few days later, I encountered the clam once more. A friend and I were driving along the motorway when I saw the clam dragging itself wearily along the inside lane. It was heading away from Prague. Could it be returning to the ocean after the failure of its mission? Might they now send someone else? Could it be that next time I’m chased through the city at night, my pursuer will be a squid?

translated by Andrew Oakland, from The Book of Prague (Comma Press, £10.99)

first published as ‘Letní noc’ in Návrat starého Varana in 1991

—

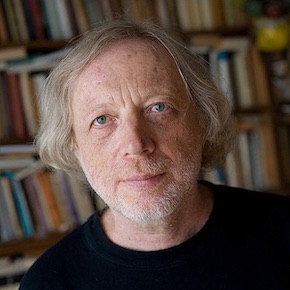

Michal Ajvaz, born in Prague in 1949, is a fiction writer, poet, essayist and translator whose books have been published in 24 languages. His many prizes include the Jaroslav Seifert Prize (2005) for the novel Prázdné ulice (Empty Streets), the 2012 Magnesia Litera Award (Book of the Year) for the novel Lucemburská zahrada (The Luxembourg Garden), and the 2020 State Prize for Literature in recognition of a lifetime’s work of excellence. The novels The Other City, The Golden Age, Empty Streets, and Journey to the South are all published in English by Dalkey Archive Press.

Andrew Oakland was born in Nottingham in 1966 and is a graduate in German from the Universities of Southampton and Nottingham. He taught for ten years at Masaryk University in the Czech city of Brno, where he still lives, and has been a freelance translator from Czech and German since 2005. Novels in his translation include Michal Ajvaz’s The Golden Age (a Fiction Finalist at the 2011 Best Translated Book Awards), Empty Streets and Journey to the South, Radka Denemarková’s Money from Hitler, Martin Fahrner’s The Invincible Seven, Kateřina Tučková’s The Last Goddess, and a new rendering of Josef Lada’s classic work for children, Mikeš.

The Book of Prague, edited by Ivana Myšková and Jan Zikmund, also featuring stories by Bohumil Hrabal, Irena Dousková, Simona Bohatá, Jan Zábrana, Petr Borkovec, Marek Šindelka, Patrik Banga, Veronika Bendová and Marie Stryjová, is published in paperback by Comma Press.

Read more

@CommaPress