Corsets of conventionality

by Ursula PhillipsZofia Nałkowska (1884–1954) was one of the most important Polish writers of the first half of the twentieth century, prominent in public life and a figure of European significance, whose major works have been translated into English only since 2000. She was a pioneer of psychological modernism. Apart from novels, short stories and plays, Nałkowska kept a lifelong diary, edited and published many years after her death (1970–2001). It is this diary that forms the basis of Jenny Robertson’s From Corsets to Communism, the first biography of Nałkowska in English, along with several other sources, notably the monumental biography published in Polish in 2011 by the editor of the diary, Hanna Kirchner. The diary has not been translated into any language, so the inclusion of substantial quotations in Robertson’s own translation is a significant contribution to their visibility.

In contrast to Kirchner’s, Robertson’s biography is not an academic work, but aimed at the general reader, although this does not prevent it from being a useful introduction also for students and researchers. It is written in an accessible and attractive style, as befits Robertson’s past record as a poet and populariser of Polish poets in her own translations. Quoting Nałkowska’s contemporary, Jarosław Iwaszkiewicz, who wrote following publication of the first story of her Medallions: “If you had written in French or English or even in Norwegian you would have been the most famous writer in the world,” Robertson highlights the perennial dilemma of translators trying to popularise so-called ‘minor’ or ‘periphery’ literatures. These stories alone, based on witness accounts of the Holocaust, reveal Nałkowska to be an insightful critic of fundamental patterns of human behaviour. Robertson likewise emphasises, on the basis of other works, Nałkowska’s interest in the psychological origins of ‘evil’ and crime, including her own theory of war, empathetic engagement with issues relating to women’s sexuality and social marginalisation, as well as opposition to political injustice and violence, not least during times of transition.

While it is a moot point whether Nałkowska ever wore a corset, ‘feminism’ for Nałkowska expressed itself as a demand for equal sexual rights, what she called the ‘whole of life’, rather than involvement in women’s movements.”

Robertson maintains an appropriate balance between Nałkowska’s private life (relations with both parents, sister, lovers and husbands) and her literature, and between her literature and her involvement in public life, where she found herself close to power thanks to her marriage to Jan Gorzechowski, a close associate of Józef Piłsudski, and like him a former freedom fighter turned tyrant. Nałkowska’s world is well-contextualised historically. She lived through fundamental upheavals in one of the theatres most affected, including foreign occupation during two world wars. Key aspects of her experience are reflected in the title From Corsets to Communism. While it is a moot point whether Nałkowska ever wore a corset, Robertson explains that the title refers to the ‘corsets of conventionality’ against which she rebelled as a young woman, emphasising at the same time that ‘feminism’ for Nałkowska expressed itself as a demand for equal sexual rights, what she called the ‘whole of life’, rather than involvement in women’s movements. Communism, meanwhile, refers to her decision after WW2 to throw in her lot with Poland’s new rulers. Robertson describes this unjudgementally, charting Nałkowska’s gradual disillusionment and moral frustration; during her final years, perhaps for fear of the authorities, the diary becomes a record of routine meetings and daily chores and ceases to record her innermost thoughts.

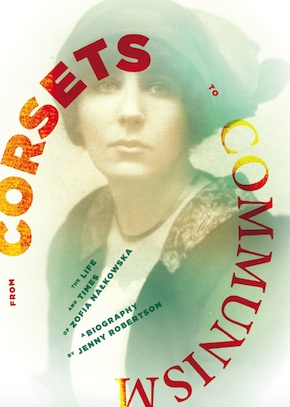

Late portrait of Zofia Nałkowska © Władysław Sławny/Forum

Perhaps the most striking aspect of the diary, reflected in Robertson’s book, is how it portrays a very different woman from Nałkowska’s self-cultivated public persona; both before and after 1945, she was perceived as a grande dame of the literary scene, tall and physically imposing, much-admired and self-confident. In the diary, it is clear how much she suffered, not least from low self-esteem: short of cash throughout her life (she depended on her writing which brought in little money), frequently ill, coping with the early onset of deafness and tinnitus, emotionally abused by her sexual partners, often depressed and always struggling with the creative process.

It remains an open question what constitutes Nałkowska’s most important legacy: is it her witness to the Holocaust as expressed in Medallions, the achievement for which she is generally recognised in the Anglophone world thanks to Diana Kuprel’s translation (2000)? or is it her controversial novel Knots of Life (1948, 1954), which together with earlier works of the 1920s and 1930s provides a devastating critique of the interwar state and the role of her own generation within it? Jenny Robertson does not provide a definitive answer to this question, but she certainly gives us much food for thought.

Jenny Robertson studied Polish at Glasgow University and spent a post-graduate year in Warsaw where she continued her exploration of Polish life and culture. An author of poetry, children’s books, historical fiction and non-fiction, she writes for the Holocaust journal Prism (Azrieli Graduate School, New York). From Corsets to Communism is published by Scotland Street Press.

Read more

@ScotStreetPress

Ursula Phillips is a translator of Polish literary and academic works and Honorary Research Associate of the University College London School of Slavonic and East European Studies.

ucl.ac.uk