Darker than a deep silence

by Matteo Righetto

“Evokes scents, sounds, whims of that small far wprld, between peaks and springs.” Corriere del Veneto

It was the dead of night – more precisely two o’clock on the morning of Monday 29th September 1893 – when Augusto De Boer and his daughter set off.

Such was Jole’s emotion, she could feel her heart bursting. Her hands were cold and sweaty and moved in an awkward way.

She had got out of bed barely half an hour before their departure, but in truth she had not slept a wink. She had lain awake all night listening out for wild animals, trying to imagine what awaited her in some unknown place at some unknown time, out there beyond the hills that had always marked the limits of her world.

Her father was already up, waiting for her in the shed: four walls of rough stone and old planks of wood, the upper part of which, covered in grass and moss, served as a hayloft.

A few years before, a small wild blackthorn had sprung up in a corner of the roof, probably as the result of a kernel fallen from a redstart’s beak. Augusto had decided to leave it there because he liked the idea of having a fruit tree over the hayloft: offering food to the birds, he said, brought good luck. In April the branches filled with snow-white flowers, and in September they were laden with little round purple sloes of which the blackbirds and thrushes and tits were very fond. Augusto did not want his children to gather these fruits, since he considered them an offering to the birds of the wood, a kind of reward for these frail creatures, a mark of fraternal solidarity.

Agnese and Antonia greeted Jole in the kitchen without lighting any candles: the customs officers might have spotted their nocturnal movements even from a distance. Sergio was unaware of anything and continued to sleep. Agnese gave

Jole a cup filled with hot milk and she savoured it a little at a time, taking small sips, thinking about when she would again be able to taste anything like it.

She knew that if everything went smoothly, according to the plans laid down by her father, she would be back home in three or four days at the most, but she knew that even a mere handful of days would seem to her infinitely longer than that.

At the door, her mother and sister embraced her in silence. She summoned up her courage and went to join her father.”

She donned heavy garments in which tobacco was concealed everywhere, put on her boots, tied her long hair with a length of thick hemp twine, loaded her rucksack on her back and left the house. At the door, her mother and sister embraced her in silence. She summoned up her courage and went to join her father in the shed.

During those twenty steps that separated her from the shed, Jole took a deep breath. The sky was damp and cold, and a light haze brought with it the strong penetrating smells of early-autumn nights, leaving them hanging in mid-air: mist-soaked moss, moulting animals, sickly-sweet late-blooming flowers, shrivelled wild berries, withered mushrooms.

Augusto had already harnessed Hector, as Jole had called their mule, loading him with everything, but above all with tobacco, in addition to the tobacco that father and daughter were keeping hidden in their clothes and shoes and ankle bandages. It was sealed within dozens of pockets, cavities, compartments and internal pouches, invisible to any possible search.

That year the harvest had been good and Augusto had somehow managed to hide almost a hundred kilos, in various forms: pressed leaves, shag and powder. There was something for every taste and every vice.

The two exchanged glances in the darkness of the shed, the whites of their eyes the only things that glowed in the dark. In the enclosure, the hens clucked drowsily, annoyed at being disturbed. Jole stroked the cow, Giuditta, one last time, then walked out and waited for her father to join her.

Her hands were still cold, her movements still awkward. Her heart began beating even more loudly than before, and the persistent smell of manure penetrated her nostrils as if trying to cling to her breathing, to travel with her and be with her for the whole journey.

“Let’s go,” Augusto whispered, slinging the rifle called St Peter, already loaded, over his shoulder, next to his rucksack, and so saying he closed the door of the shed. They slowly passed the vegetable garden and came close to the door of the house. There, Agnese and Antonia approached like two shadows to bestow their final farewell. Agnese embraced her husband, then put a red kerchief around her eldest child’s neck. Antonia kissed both of them.

Nobody uttered a single word.

The two of them set off. Augusto walked in front of the mule, holding the reins and leading the way, and Jole followed a few paces behind. They walked slowly, moving away from the house towards the steep path that slipped down into the woods beneath the walls of rock and led to the valley and the great river.

Antonia ran back into the house, perhaps so as not to cry, whereas Agnese mustered the courage to follow them with her eyes until the last moment, until they were swallowed like ghosts, first by the night fog, then by the dark forest of broad-leaved trees.

Her Jole was fifteen, Agnese thought, no longer a child but not yet a woman. She prayed to the Madonna for her and for her man. At that very moment, Jole took from a pocket a little wooden horse, one of those she had carved the previous day with her little brother.

“I’m a real smuggler,” she whispered into its wooden ear.

Then she hugged it to her chest and felt less afraid.

***

The path was slightly muddy, with a thin layer of dew, and the dampness of the night had softened the ground and made the backs of the stones slippery. Once they had moved into the heart of the woods, Jole and her father had to be careful not to slip and fall.

All at once, she took a few steps forward and had to rest a hand on the mule’s back to avoid losing her balance.

It is always strange to begin a journey downhill.

She would have liked to say something, ask her father how long it was going to take them, but she remained silent.

Over the preceding weeks, Augusto had told her that they should speak as little as possible during the journey. The customs men were hiding everywhere, you should never be too trusting, not even when you thought you were safe.

Remembering these words, all Jole could do was think about what she would have liked to ask him and try to find the answers to her questions for herself.

Augusto immediately set a gentle, steady pace, although the descent was gradually becoming more difficult and dangerous because of the steep drops that loomed suddenly at the sides of the trail.

God knows if the sunlight filtering through the branches has a name, Jole thought, listening to the rhythmic sound of her own boots. God knows what it’s called in the big cities.”

Soon the path contracted even more, until it was as narrow as the mule’s belly. With a glance, Augusto ordered Jole to return to her place. Although a blurred crescent moon emerged from the blanket of fog and cast a weak glow over the world, the inside of the forest was pitch black, and Augusto was advancing from memory rather than checking where he was putting his feet. Then again, he knew this trail like the back of his hand, he had been the first to open it up, and he had kept it open over the last few years, partly because he had knocked down a few trees and regularly cleared bushes and brambles, although every summer they reconquered space and ground.

They were continually accompanied by disturbing noises and the cries of animals, almost as if they were being welcomed to a kingdom barred to human beings.

As she walked, Jole shivered a little, thinking how different the woods were by day and by night. By night all woods are the same, she told herself, and all are frightening. She thought of the forest of broad-leaved trees she was going through, a forest she knew well but which seemed an unknown quantity to her in the dead of night. She recalled the hues of early autumn that had changed the colour of the woods in the last few days, the reds and yellows and ochres that, if it had been day, would have shone on maples, chestnuts, beeches, birches, oaks, alders and hornbeams. And she imagined the thousand scents those trees would have given off and the constant, infinite play of light that the sun would have set in motion as it filtered through their branches.

But here and now, everything was dark, darker than a deep silence.

God knows if the sunlight filtering through the branches has a name, Jole thought, listening to the rhythmic sound of her own boots. God knows what it’s called in the big cities.

Augusto came to an abrupt halt.

They both stood there motionless, Augusto even holding his breath as he looked around. At that moment, a weak ray of moonlight percolated through the mist and lit up his face and Jole was able to make out his attentive, vigilant, alert look, like the look of a roebuck that has sensed a dangerous presence. She concentrated on certain details of her father’s tense face, which seemed carved out of porphyry. It was barely visible, and yet in it, in the abrupt, cautious movements of his eyes, Jole glimpsed something mysterious, something bestial, which she found hard to understand, something that had taken shape with the passing of the minutes and the progress of their steps. She was even more moved.

After a few moments, without saying anything, Augusto resumed the downhill path, and she immediately followed him, surrounded by these disturbing noises, these animal cries coming from every direction – screeching, howling, whistling, breathing and whimpering – which scared Hector, too, and actually slowed him down.

***

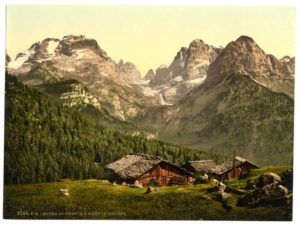

During the descent, Jole slipped several times and on a couple of occasions actually ended up on her backside. She got up again immediately, without her father’s help. Just over an hour after leaving home, the two De Boers, through provident changes of direction and sudden shortcuts, got to within no more than a hundred paces of the Brenta. Remaining well hidden amid the hazels, they stopped to catch their breath and listen to the water running smoothly and continuously over the rocks and stones that lay strewn on the riverbed, having been carried down by the flood three years earlier. In the meantime, the mist had started to clear, giving way to an ever clearer sky in which, apart from the moon, they even began to make out a handful of stars. Beyond the river, on the side opposite to where father and daughter now stood, they could make out the imposing wall of forest that rose all the way up to the slopes of Mount Grappa.

Mouth of the Brenta and Brenta Group, Tyrol, Austro-Hungary, c. 1890. Detroit Publishing Company/Wikimedia Commons

Augusto observed the river, then examined the sky and finally looked at his daughter.

“It was better when it was foggy,” he said in a low voice, “although there aren’t usually any customs men here.” Then he raised his right arm and pointed at something only he could see. “We have to ford the river at that point to get to the right bank. We’ll cross the valley, climb back up the mountain opposite and then go north-east, towards the border.”

She nodded, and then immediately thought again of these words: in fifteen years she had never heard her father say so many together, one after the other.

Augusto moved slowly, holding the mule’s reins tightly in his right hand, and Jole stuck close to the animal. Remaining deep in the brush, they descended for another thirty metres or so and at last came to the dry, stony bank of the river. Without wasting any time, they headed straight for the water. Even though the noise was growing ever louder, they could hear the distant clangour from Tezze, upriver, where the Austro-Hungarians were finishing the railway that came down from Trento, made its way through the Sugana Valley and ended up on the border with the Kingdom of Italy a few kilometres further north. For a year now, work had been continuing day and night, thousands of soldiers of the emperor and workers coming and going between the river and the nearby stone quarries, in lines and in groups, as orderly as tireless ants, equipped with pickaxes and shovels and handcarts loaded with dynamite.

To the north, towards Trento, teams of workers were digging and opening up tunnels beneath the mountains of the Sugana Valley, and further down other teams of workers were blowing up the quarries to extract the stones that they then would chisel down to size in order to lay them where other men would place sleepers of wood from Carinthia or the Fiemme Valley. Other workers were heating iron in kilns set up in open country and passing it on to teams who specialized in placing and fixing the rails. Controllers travelled about in handcars, checking the quality of the work, and everywhere there were iron bridges and subways and supporting walls built with cement from Kufstein. All this endless, colossal work in order to build the tracks on which one day a steam locomotive as black and shiny as an oil spill would run. And all this technical novelty, all this devilry, came from other countries, God alone knew how distant.

Jole did not even know what a train was, nor was Augusto able to imagine one, even though one summer afternoon he had looked down from a height and seen a large number of soldiers busy laying these strange iron rails that followed the course of the Brenta.

He had heard talk of them. There were those who said that the coming of the railways would eliminate borders and bring well-being, wealth and progress to everyone, but Augusto De Boer was not at all convinced. The way he saw it, the poor would remain poor for ever and borders, all kinds of borders, would never cease to exist. At most, they might continue to move a bit this way and a bit that way, as they had done ever since man had come into existence on the face of the earth.

He and his daughter, though, saw nothing of all this turmoil, and they wisely kept their distance as they approached the river, at least three kilometres south of the borderline.

from Soul of the Border (Pushkin Press, £12.99), translated by Howard Curtis

Matteo Righetto was born in in 1972 in Padua, where he teaches literature. Many of his works take place in beautiful mountain landscapes that he knows deeply, having visited them since childhood backpacking with his father. Soul of the Border, the first of his works to be published in English, is out now in hardback and eBook from Pushkin Press, who will publish the second title in the trilogy in 2019.

Matteo Righetto was born in in 1972 in Padua, where he teaches literature. Many of his works take place in beautiful mountain landscapes that he knows deeply, having visited them since childhood backpacking with his father. Soul of the Border, the first of his works to be published in English, is out now in hardback and eBook from Pushkin Press, who will publish the second title in the trilogy in 2019.

Read more

@PushkinPress

Author portrait © Giacomo Giovanni Stecca

Howard Curtis has translated more than fifty books from French, Italian and Spanish, including works by Pirandello, Flaubert and Balzac. His translation of Pietro Grossi’s Fists won the Premio Campiello Europa in 2010.

@HowardCurtis49