On the delta

by Haroldo Conti

“One of the great Argentinian writers.” Gabriel García Márquez

Between the Pajarito and the river that’s an open sea, turning sharply northwards, narrowing and narrowing at first, to almost half its size, then widening again and drawing curves towards its mouth, coiling in on itself, secluded in the first islands, is the Anguilas Stream. Beyond the final bend the open sea breaks into view, rucked up by the wind. Even in all their vastness, the waters here are shallow. From the mouth of the San Antonio to the mouth of the Luján, everything is sandbank. The Anguilas empties out into the middle of this sandbank, amidst a field of reeds. Depending on your viewpoint, the place looks pretty bleak, and on a day that’s grey, and with a blow, it disquiets any man.

Far off to the left, dark and silent like a ship, lies the isle of Santa Mónica. Far off to the right, fading blue into the distance, the shore. And if the day is clear, towards the south, like a lattice, the planes of grey and white of the highest towers in Buenos Aires can be seen, under the oppression of a constant grey cloud.

When strong winds from the north or the west cause a bajante, the water level plunges, and an area of sandbank rises up above the surface; after the bajante, it seems that terra firma has extended its dimensions, the springs that cross the reed bed feigning newly settled streams. There are fishermen who venture onto this new land, which is wet and desolate, but if they don’t lay out the lattice matting from their boats, they sink into its mud, and almost to their knees.

The most recent of the charts marks the mouth of the Anguilas with a fish’s silhouette, to show abundant catches here, but this is rather doubtful. In any case, there’s nothing more daft than taking note of references like these. If there are certain fishermen who come to lay their nets here, at night, and in the week, it’s owing more to the fact that the area is little frequented at those times. This wretched habit makes them think the place is theirs, and the unsuspecting soul who takes advantage of their head rope runs the risk they’ll sink his boat, and with gunfire, too. Once upon a time, Polo had to shoot his way out, letting fly at either bank, and then towards the reeds, with that aged English shotgun, the 1903 Purdey with its sawn-off steel barrels that he kept for such occasions. He bottom-trawled his nets across this very stretch of sandbank, seizing on a surge, and once out on the open sea he pulled the catch on board. He sold in San Fernando when a little time had passed. But this is now an old tale. It’s a long time since Polo disappeared. The fishermen are still around, though, and in the week, at night, they lay their nets.

…

He was working with the old man almost until spring. It was nine years or so the old man had lived on the Anguilas, and for seven he was living from the reeds. He came down from the Romero in the year of ’48, where, from ’34, he’d been working in the apples. It was the year of ’47 that the Elbita, a six-ton fruit barge, foundered, drowning the only son who’d stayed with them. So then in ’48, and already getting old, he came to the Anguilas in the Elbita’s little rowing boat. He made two journeys. One with their belongings, and the other with the old girl and Urbano, the dog, and two or three chickens.

They made themselves a home in one of three empty cabins, the one closest to the river mouth, just where the Anguilas joins that blind little stream that peters out a little further on, often thought to be a prolongation of the Anguilas by those who don’t know any better. He’d been confused himself in ’48.

Neither the old man nor Boga ever said more than was needed. And yet they understood each other perfectly. At dawn, they walked into this green and humming solitude that swayed with every gust of wind. Each one made his own path.”

The cabin had two rooms, or really just the one, which was divided by a mud wall. As the years went by, the old man added two more rooms and put up a latrine, which he sited at the far end. Time made a group of the various parts, bringing them together in a dark and bulging mass, with two or three little openings, even darker still. Its base was very high and pretty badly bound together, with several rotten cross-beams. Over time it gave way on one side, the weakest, so the cabin gently leaned in that direction.

The stream was so narrow here you couldn’t build a jetty. It was doubtful that the old man would have built one even so. Instead of this, he fixed a willow gangway to the bank, and tied the little boat from the Elbita to a cross-beam.

Everyone’s aware that the more you crop the reeds, the more they will grow. When many folk are cropping them, and cropping them too hard, a market glut will follow, and no one’s going to pay much for another shed of reeds. There’s nothing more accursed nor more wretched. And, sad to say, there seem to be people on these islands who do nothing else.

Something like this happened just a couple of years ago, and the year after that, this last, no one cropped the reeds, or didn’t try to sell, at least. The old man didn’t either and hunger almost killed him. But he faced it all with dignity, on most days eating catfish, or, come the winter, silverside, which he called latterino, or else lattarina, and which are, after all, the rations of kings.

And so, the following year, the last one for the old man, the reeds picked up a bit.

Boga came along when the cropping had just started, and they’d worked together since, until this spring was almost here.

In the dead year, which is to say the year before, the old man finished work on the straw-and-willow refuge he’d begun three years earlier, which was when Urbano died. He built it very low and didn’t put in any walls, but placed it on a rise, beside a solitary ceibo. The old man dug the floor out to a depth of half a metre and built a sort of stove into one corner. They used it at midday or when the weather turned inclement. They ate a piece of pork belly with sea bread, then they drank some maté. Sometimes Boga grilled a catfish, when they’d caught one on the line, but really he preferred to take them home. Then they slept a while. The old man slept sitting up, with his head laid on his knees and his arms around his legs.

Neither the old man nor Boga ever said more than was needed. And yet they understood each other perfectly. At dawn, they walked into this green and humming solitude that swayed with every gust of wind. Each one made his own path, stepping through the water. At times it reached their thighs, but they didn’t seem to notice. Beyond the wall of green, out towards this River Plate which the folk here call the open sea, they heard the water murmur as it rolled tirelessly across the sandbank. The distant, sorry screaming of a limpkin. The suffocated din of a motor launch, still further off. The sand boats with their rhythmic beating diesel engines as they travelled the canal. The boiling of the Glosters in the clouds as they leapt the sky in one, chased by their own din.

The old man had a skill – never mind his age. When he gathered up the reeds from where he’d laid them to dry, spread out on the rise around the refuge that he’d built, he did it with a briskness that was staggering to see, and even with a certain elegance. He caught them in one swipe and, continuing the movement, shook the reeds out straight and then bound them in a sheaf, tying each one round with another reed in a final little flourish. Boga had neither this skill nor this degree of devotion to a matter that he didn’t think called for artistry. In fact he felt a little bored, although he had a patience or, to call it what it really was, an indifference that never tired. What gave him pleasure was to gaze out from the refuge at the carpet of reeds, which he’d spread out with the old man and which now shone darkly in the sun, giving this lonely corner the appearance of an island in the tropics.

When it was the time, the old man swapped the reeds for cat’s tail or bulrush. It didn’t look the same when there was straw laid on the ground, but it served them just as well.

At times they took along with them the cream-coloured dog, but the old man would get angry when it went off in the reeds and barked all the time, so he preferred not to bring it. But the dog would turn up in any case, at some point in the day, and start with its barking. The old man would let it go a while, as if he hadn’t noticed. And then he’d stand up straight, like a spring, and fire off a curse that seemed to land right on the bullseye. They heard the rushing noise from in among the reeds, and listened as it went away towards the house. The old man didn’t feel much real fondness for this dog, although he saw it had its uses. The old woman, on the other hand, was fonder of the cream-coloured dog than of Urbano.

When Boga asked the old man if he’d lend him the double-barrelled shotgun, which had been hanging near the headboard since the day he’d arrived, the old man looked him in the eyes and didn’t say a word. Two months after that, when you’d imagine he’d forgotten, he took the shotgun off its hook and put it in the passage, leaned it up against the wall right next to Boga, who was lying there, puffing on a cigarette. Boga took the gun onto the boat from that day on, and kept it on the floor between his feet while he was rowing. He worked out in the reeds with the shotgun there to hand, hanging on a forked stick that he’d pressed into the mud. When a limpkin or another bird he thought was worth the trouble paused nearby, he gathered up the shotgun with a straightening of his arm. The shot rang harsh and sad, like a punch across the vastness, rolling on and on across the undulating field, and then across the water, and after that the nearest islands. Once back in the house, down on the floor of the veranda, he cleaned and stripped the shotgun down, absorbed in his meticulous attention to the work. It was a Belgian shotgun, a Pirlot & Frésart, that took 12-cal cartridges of 65 mm. He would have given his all to own this gun, but he knew that the old man prized it just as much as he did. What he might instead dare ask him for, at some point, was the Sheffield knife he used to cut all kinds of things, including his cigars.

The old man did his work barefoot, in trousers that were worn out, cut off just below the knee, and wearing two jackets which he tied round with sisal. Boga himself wore a sweater with a high neck and a pair of long johns with a fly that was sewn closed. It was dirty work, and hard, and it numbed them by degrees. The wind buzzed round their heads continuously, on most days, rather like a swarm of wasps, dizzying them and stabbing at the skin on their faces.

Boga took the lines in when the light began to fail, and then they would go back to the house, dead tired and ill-tempered. He didn’t take his long johns off but pulled trousers over them and lay down in a corner of the passage. The old man, on the other hand, gave himself a wash that seemed to go on an eternity, then put on a clean, fleece, collarless shirt, full-length trousers and a pair of Pirelli boots. Then, on the veranda, he sat and used his Sheffield knife to cut one of his Avantis and smoked it until dinner time, very slowly, with the cream-coloured dog beside him, looking at the river, looking at the heavens, looking at the night begin in silence.

Extracted from Southeaster, translated by Jon Lindsay Miles, out now from And Other Stories.

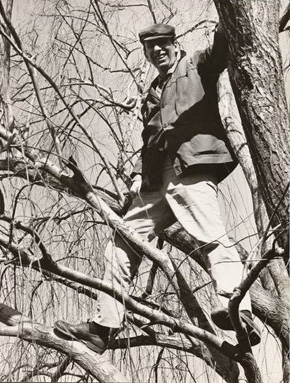

Haroldo Conti was born in the province of Buenos Aires in 1925. After the publication of Southeaster in 1962, he went on to write three more novels and several short story collections. He is the recipient of several important literary prizes, including the Casa de las Américas Prize. He was arrested after Argentina’s military coup in 1976, and remains on a list of the ‘permanently disappeared’.

Haroldo Conti was born in the province of Buenos Aires in 1925. After the publication of Southeaster in 1962, he went on to write three more novels and several short story collections. He is the recipient of several important literary prizes, including the Casa de las Américas Prize. He was arrested after Argentina’s military coup in 1976, and remains on a list of the ‘permanently disappeared’.

Portrait of Haroldo Conti by his son Marcelo

Jon Lindsay Miles lives and works in southern Spain, where he publishes as Immigrant Press and teaches English conversation at an outpost of the University of Jaén. His translation of Southeaster is published by And Other Stories in paperback and eBook. Read more.

immigrantpress.org

@ImmigrantPress