Dim background figures

by Mika Provata-Carlone

“A vital contribution to the construction of an alternative women’s history… quite brilliant.” Guardian

Among the bold colours and radically liberating shapes that conjured up so indelibly the world of the Bloomsbury Group painters, between the layers of meaning and style of the new women writers, under the shadows or glaring light of history, and at a tantalising distance, both flirtatious and cautionary, from the figures who dominated early 20th-century British art, science, politics and public life, could be seen, at unpredictable, impulsive interludes, some “dim background figures… turning out to be Oliviers – varieties of Oliviers,” Virginia Woolf was to write in her diary.

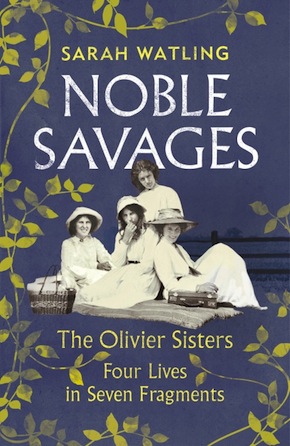

The four Olivier variants Woolf is referring to, Margery, Brynhild, Daphne and Noël, were the daughters of Sydney Olivier, himself the son of an Anglican clergyman who would eventually become a prominent British statesman, a governor of Jamaica, the Secretary of State for India, an ardent Fabian and one of the forefathers of the Labour party as well as a Baron (and the uncle of Lawrence to boot). Contrary to what Woolf perhaps saw as an effaced immanence, Sydney would describe his daughters as capable of being “unthinkingly cruel as savages. Sometimes they were savages”, and Sarah Watling in her new biography Noble Savages: The Olivier Sisters – Four Lives in Seven Fragments seeks to evoke a more nuanced socio-biographical, even philosophical understanding of what she sees as the sisters’ otherness, wildness, ultimately irresistible uniqueness and feral strangeness: their foremost quality that first appealed to her, as she admits, was that “they had gone through life intriguing and alarming people in turn.”

Part of the ‘savagery’ was their being at the heart of what was known as the ephemeral, whimsically utopian group movement of the Neo-Pagans (once more, this is Woolf’s term), and most, if not all of the glimpses we have had so far of their liminal presence, private lives or radical minds, have been through the perspective of that particular moment in time and state of being. More especially, the Olivier sisters (in nearly all their permutations) have been cryptic footnotes or tempting undertones to the life, idealised in its magnificence and tragedy almost beyond recognition, of the poet Rupert Brooke. As the aura of “the handsomest young man in England” increased following a series of impassioned, romanticising, even revisionist biographies (Christopher Hassall, Michael Hastings), the neo-Byronic otherworldliness of this intangibly larger-than-life man and poet also came to the foreground. Suddenly there was an alternative, if not a serious contender, to the fabulous charm of Bloomsbury, to that realm of wonder and scandalousness, brilliance and darkness, genius and the most exquisite distillation of the fragility and precariousness of life and the human mind. Brooke’s own circle, which included the more loosely defined Neo-Pagans and the more recognisable Apostles, began to be explored for its own magnificent extravagance, its tangential trajectory through the Modernist firmament. Following the publication of David Garnett’s three-part memoir The Golden Echo (soon dubbed “the golden ego”), interest grew fervently and exponentially for Bloomsbury’s many outsiders (to use the term of Garnett’s biographer, Sarah Knights). In the hands of Paul Delaney, and his suggestively titled The Neo-Pagans: Friendship and Love in the Rupert Brooke Circle, the Neo-Pagans were established not only as the new Romantics, but especially as the Ur-moment of Brooke’s own genius and fatality. For his part, Michael Holroyd and his controversial hagiography of Lytton Strachey would literally tear down the Bloomsbury ivory tower, clearing the ground for human rather than aestheticised interest, for the telling of the simple human stories, warts and all, behind the legends and their heroes.

Perceived unacceptability and a fiery independence and resistance to male or any social norms, a maverick education and background, and a determined safeguarding of a private space are the trademarks of Watling’s Olivier sisters.”

Watling’s story of the Oliviers also starts, inevitably, with Brooke, and with the reluctance of the youngest sister Noël to cooperate in Hassall’s biography, “a traditional feminine means of resistance”, according to Watling, that “enraged the keepers of Rupert’s flame… She was supposed to sacrifice herself – for that is what giving up secrets, speaking frankly of buried memories is – to the service of a Great Man and his legend. She refused, which was an unacceptable act of independence.” So-perceived unacceptability and a fiery independence and resistance to male or any social norms, a maverick education and background, and a determined safeguarding of a private space are the trademarks of Watling’s Olivier sisters, the features that make them distinct rather than dim figures of their time, worthy of the foreground of our understanding of an era, a frame of mind, a cultural, social and historical moment. Of even more vital importance, from a personal as well as an anthropological or socio-ethnological point of view, Watling argues, is their dynamics as a sisterhood, as a closely-knit female cell that owed both its strength and its tragedy to its symbiotic powers. Noble Savages is a thoroughly researched, finely written and argued chronicle of these four lives, but also of many aspects of the female consciousness in the early 20th century, with strong and poignant resonance for our own time.

Resplendent around the lives of the four sisters, and the lives of those whose destiny they marked (or sometimes marred), is the record – social, historical, literary – of an entire era, and Watling has an exceptional talent in intertwining the public with the private without compromise or infidelity to either. As a biography, complex and multiple at that, this is engrossing; as the retrieved stories of many lives, it is gloriously rich, immensely satisfying. As a reflection on the paths of feminism, female emancipation and professional praxis, it is rivetingly dramatic, exposing the cost and ramifications of choices made or abandoned.

Beginning with Sydney (if not with the rather unnerving Reverend Henry Arnold Olivier, his father), the story is one that combines quintessential British qualities: the path from hard-earned respectable obscurity to a ferocious sense of public duty, as well as the inherent contradictions in the pursuit of the simple life, a just society, and a progressive radicalism that also intended to satisfy a desire for public visibility and status and an unquestionably powerful personal and political ambition. Sydney’s circle was irreverently ‘advanced’, the hub of the most prominent liberal intellectuals, at the same time that it was at the very centre of power politics. It boasted writers such as H.G. Wells, G.B. Shaw, Ford Maddox Ford, Conrad and Galsworthy, and especially the Fabians – the poets Edward Carpenter and John Davidson, Havelock Ellis, a taboo-breaking specialist in human sexual behaviour, the socialist Edward Pease, the pioneering educationist and theosophist Annie Besant, the LSE founders Graham Wallas and Sidney Webb and the latter’s wife Beatrice, the first labour PM Ramsay MacDonald and Emmeline Pankhurst. Sydney would marry Margaret Cox, sister of the Manchester Liberal Harold Cox.

In many ways, the Oliviers are a potent mix, a pre-Durrell bunch with a vengeance, in that they are in equal measure extravagant misfits and keenly aware of a sense of exceptionality.”

At their home, nicknamed ‘Dostoevsky Corner’, they would give refuge to political exiles from across the world, from the Armenian poet Avetis Naxarbek to Prince Kropotkin and Sergei Stepniak. One of the girls’ nannies was the formidable Gertrude Dix, a less well-known writer of proto-feminist novels who saw her task as “helping to rear beautiful children for the state” by doing away with Victorian strictures and Red Queen mottos. The Olivier sisters were perhaps not the most evidently malleable state material, however: “if these are only socialists, what must anarchists’ [children] be [like]?” In many ways, the Oliviers are a potent mix, a pre-Durrell bunch with a vengeance, in that they are in equal measure extravagant misfits and keenly aware of a sense of exceptionality, of importance and public standing, a colonial sense of authority and calling (yet without the sense that this always included a developed socio-political consciousness and acumen), as well as a sense of failure, decline, no-man’s-landness, once the destiny of the daughters diverged from the more exalted path of their father.

Sydney would give his daughters not imagination, Watling argues, but a sense of the mechanics of purpose, he would bequeath to them strong determination, clear if unfocused ambition, a sense of their right to a full public role and potential, regardless of their expected gender roles – they were, in that respect, New Women with a vintage pedigree. He would also create for them a world where liberal idealism, spiritualist ‘science’ and hard pragmatism (the ‘Gas and Water Socialism’ of the Fabians) coexisted in curious and not always happy tandem; where a highly critical view of British government strategies (as for example in Sydney’s opposition to Cecil Rhodes’ and Chamberlain’s southern Africa policies) would live side by side with ardent political ambitions. The Olivier world was a Janus-faced one, it was uninhibited, and full of a prudish eroticism, it was entitled, naïve, determined, visionary, and possibly seriously disoriented. The sisters’ early fascination with what Brooke called “splendid lives”, that “Heaven of Laughter and Bodies and Flowers and Love and People and Sun and Wind”, with its cult-like veneration of youth, purity, a simple life that did not know material want or necessity, their immersion in the pervading atmosphere of discussions on politics and socialism, theosophy and the ideal society, arguably produced a motley canvas on which to sketch out one’s life.

From a childhood in what was admittedly an untypical environment even by the radical standards of the Fabians, to the relatively explored and chartered Neo-Pagan period, the Oliviers can be said to have staked a strong claim on the imagination of their contemporaries and on that of later historians. Watling’s strength is that she persists beyond that moment of mythography, of vignette romance and of a perception of female identity as serving only the purpose of being someone else’s tragic muse. She explores each of the sisters’ four lives individually and as a female phenomenon, in order to fashion an insightful, composite tableau of a new awareness of womanhood that is raw, unformed, symbiotic and what one can perhaps term ‘neo-matriarchal’, at times confused, yet powerful nonetheless. In a way, the resulting narrative is part of the foundation myth of Englishness: a pixie-like oddness and charm that combines unapologetically with an unwavering sense of self and of a rightful place in history.

Sir Sydney Olivier with his four daughters on horseback in Jamaica, 1903 (left to right: Margery, Daphne, Brynhild, Noël). Wikimedia Commons

As part of that same discourse of the genus and its role in the formation of a personal, national or historical identity, the Olivier sisters could have easily been compared to the Stephen sisters or siblings, or to C.S. Lewis and his brother Warren, to the Strachey brothers or even to the Brooke siblings, a direction Watling does not follow. Instead, she opts for what is at times a relentless microfocus on these four lives, perhaps reflective of their tightly packed sisterhood, which, for all their rebelliousness, left very little breathing space (or indeed any space) between them: almost invariably, Woolf speaks of the Oliviers and “their beautiful glazed eyes, glazed and fixed and melancholy” in uncannily collective terms.

Of the four, Margery and Brynhild are perhaps the ones more easily summarised: Margery would be one of the first women to study at university, yet would succumb to mental illness, variably diagnosed, defined and treated, that would remain unresolved until the end of her life. Brynhild would begin adult life as a jewellery designer, marry the art historian Hugh Popham (one of their children would be Anne Popham, known as Anne Olivier Bell, of the Monuments Men, the wife of Quentin Bell and the editor of Virginia Woolf’s diary), whom she would abandon in order to elope with Raymond Sherrard, who would also leave her soon after. Her story is one of legendary beauty, scandalous domesticity, almost absurd experiments in makeshift farming (Wells and Shaw would each have to bail her out financially), and especially of rather extraordinary motherhood. She was, intentionally or by default, the enabler of future, truly extraordinary lives – besides Anne, her son Philip Sherrard would become a formidable religious thinker, translator and writer, with a life worthy of a tale all of its own.

Noble Savages is a shrewd examination of these four lives, their daring forays into both the known and the unknown, their often meandering paths.”

Daphne and Noël perhaps lived the more remarkable lives from a biographer’s and a social historian’s point of view, and they seem to inhabit the diametrically opposed positions their lives as a whole sought to reconcile – the pure rational perception of existence with the inner need for a spiritual centre, a foundation of meaning, and a compass of purpose, away from the highly politicised socialist agenda of their father, but also removed from the absolute and forbidding aestheticism of Brooke and the Apostles, or even the Modernists. Daphne would become fascinated by anthroposophy, a variant of theosophy that claimed to be a ‘spiritual science’, a theoretically rigorous osmotic practice of reconnecting with the spirit world, deemed essential for the understanding of the purpose and meaning of life. Significantly, it also “offered the chance to be special: to embark on a journey into spiritual fulfilment that few could hope to reach.” A secessionist movement from Madame Blavatsky’s theosophy, Rudolph Steiner’s anthroposophy could be both a new religion and a radical, groundbreaking strategy for social and individual change, even though C.S. Lewis, a close friend, saw Daphne’s advocacy of Steiner’s principles as an “authoritarianist” spirituality. Daphne became an early proponent of Steiner’s theories, co-founding with her husband Cecil Harwood the first Steiner school in the UK, still in operation at Michael Hall. William Golding was one of the teachers, cajoling students into paying attention by promising to tell them stories afterwards. She would be gradually, if gently, relegated to the margins of the school’s operation and direction, and few now know of her role or even of her place in the history of British education.

Noël became a doctor and a pioneer in forging a path for women into the medical profession on a (relatively) equal standing with their male colleagues. Quiet yet indomitable, she is perhaps the one truly mysterious, and the one who protected with the fiercest vigour the sisters’ intimate stories from ogling academics and the yearning public, who saw her reluctance as “inverted vanity”. Watling’s account of her achievements and her struggles affords a unique glimpse into how unprecedented an active, public, professionally rigorous and fulfilling female life was at the time, and Noël’s ‘Olivier variety’ is indeed an extraordinary one, a crucial chapter of social history, a moving, often confessional private chronicle.

Noble Savages is a shrewd examination of these four lives, their daring forays into both the known and the unknown, their often meandering paths. Watling is keen to reveal the brilliance and inner light of the Olivier sisters, and she evinces an enthralling mastery of her subject and of its broader context. At times, the close focus creates the sense of a restricted view – as spectators we see only a small corner of the ‘momentous stage’ Watling sets out to erect, and we are ultimately left with an underwhelming sense of bafflement as to why some of these lives really did make a difference. The inspired glimpses we do get of those around them – from Woolf and Vanessa Bell, to Ada Wallas, Henry James, C.S. Lewis or Gwen Raverat, to so many others – leave the reader with a feeling of perplexed regret – what were these relationships, how did the sisters strike their balance between belonging to this wider nexus and adhering to their own reserved community? Were they somehow always suspended betwixt and between, unable to bridge their own collective solitariness with the world beyond them?

This inevitably raises the question of whether this is the story of truly extraordinary lives. Not necessarily; it would be more accurate to say that these lives were part of an extraordinary fabric of historical circumstances and almost dramatic sociocultural changes. The sisters’ connections to the true agents of these changes is what makes them into a startling mirror of their times – a partial, often clouded, arguably mystifying reflection of others and of other places and events. In this respect, Watling’s account, both factual and invented, as she states, is a superb example of annalistic history and a very sensitive engagement with voices, places, memories, and still-reverberating lives, especially with impressions, aspirations, flaws and unquenchable human feelings. It is a remarkable, highly nuanced piece of social analysis, and a sharp reconstruction of British society and life in the first half of the 20th century.

Sarah Watling holds a degree in history from the University of Cambridge and a master’s degree in historical research from the University of London. She was the 2016 winner of the Biographers’ Club’s Tony Lothian Prize for best proposal for a first uncommissioned biography. Noble Savages is her first book, published in hardback and eBook by Jonathan Cape/Vintage Digital.

Sarah Watling holds a degree in history from the University of Cambridge and a master’s degree in historical research from the University of London. She was the 2016 winner of the Biographers’ Club’s Tony Lothian Prize for best proposal for a first uncommissioned biography. Noble Savages is her first book, published in hardback and eBook by Jonathan Cape/Vintage Digital.

Read more

@JonathanCape

Mika Provata-Carlone is an independent scholar, translator, editor and illustrator, and a contributing editor to Bookanista. She has a doctorate from Princeton University and lives and works in London.