Dinner date

by Chester Himes

‘Cocoanut Grove’ at that Ambassador Hotel, Los Angeles, c. 1930–1945. Boston Public Library Tichnor Brothers collection/Wikimedia Commons

It was just turning dark when I pulled to the curb in front of the hotel. Alice clutched my arm and whispered, “Oh, no, Bob, no! I don’t feel like being refused. I’m not in the mood for it.”

“What the hell!” I said, startled. Some other girl, but not Alice; she was always going to some luncheon or dinner conference at the downtown hotels. Not so long before, one of the Negro weeklies had carried a picture of her knocking herself out down there with a bunch of city big shots. Then I got annoyed.

“You couldn’t be getting cold feet after all the bragging you’ve been doing about never being refused at all the hotels you’re supposed to’ve stayed in all over the world? What’re you tryna do, make it light on me? You don’t have to feel you got to look out for me. These folks don’t worry me, not today.”

“It’s not that,” she argued tensely. “It’s just that it’s uncomfortable and it takes too much out of me.”

“I got reservations,” I said. “You don’t think I’m taking you in cold.”

“It isn’t that,” she tried again. “It just takes an effort, Bob, and I wanted to let my hair down and have some fun.”

I was getting sore. “You seem to have enough fun with the other people you go here with. Scared because you haven’t got the white folks to cover you?”

“Shhhh!” she cautioned under her breath. “Here comes the doorman.”

“Goddamn, let him come!” I said. “Am I supposed to shut up for the help?” I knew I was being loud-mouthed but she’d shaken my poise and I was trying to get it back.

A big, paunched man in a powder-blue uniform with enough gold braid for an admiral and a face like a red-stained rock put a white-gloved hand on the car door and pulled it open. He helped Alice to the curb, touched my elbow as I followed her.

“Tis a lovely evening,” he said in a rich Irish brogue. His small blue eyes were blank.

“Fine,” I echoed, giving Alice my arm. “I’ll pick the car up after dinner.”

The great white world,’ I said flippantly, leaning slightly toward Alice as we walked the gauntlet of the room. ‘Strictly D-Day. Now I know how a fly feels in a glass of buttermilk.’”

He didn’t bat an eye. Beckoning to his assistant, a tall, sallow-faced youth in the same kind of uniform, he said, “Park the gentleman’s car,” then walked with us to the glass door and held it open. That went off all right. But when we mounted the red-carpeted stairs and stepped into the full view of the lobby we brought on a yellow alert. The place was filled with solid white America: rich-looking, elderly couples, probably retired; the still active executive type in their forties and fifties, faces too red and hair too thin, clad in expensive suits which didn’t hide their paunches, mostly with wives who refused to give up; and the younger folks no more than half of whom were in uniform, with their brittle young women with rouge-scarred mouths and hard, hunting eyes. There was a group of elderly Army officers, a brigadier-general, two colonels, and a major; and apart from them a group of young naval officers looking very white – ensigns perhaps. I didn’t see but one Jew I recognized as a Jew, and nobody of any other race at all. And I only noticed a few couples in evening dress.

It seemed that to a person everyone froze. It started at the front where we were first noticed, and ran the length and breadth of the room, including the room clerks, the porters, the bellmen, the people behind desks. Many were caught in awkward positions, some in the middle of a gesture, some with their mouths half open. Then suddenly there was a concerted effort to ignore us and only a few continued to stare.

“The great white world,” I said flippantly, leaning slightly toward Alice as we walked the gauntlet of the room. “Strictly D-Day. Now I know how a fly feels in a glass of buttermilk.”

She moved like a sleepwalker, her nails biting into my arm as she clung to it. Her shoulders were high, square, stiff, and her face was set in rigid lines, making her seem a hard, harried thirty. She didn’t speak.

“Relax, baby,” I said as we passed a group of middle-aged people. “I’ll show ’em my shipyard badge and if that don’t help, all they can do is lynch us.” I didn’t try to keep my voice lowered and the people must have heard; they drew away as we passed.

Alice blushed a deep dull red, but some of the stiffness left her. “You don’t have to prove it,” she said. “They expect you to be a clown anyway.”

“Well anyway, I’m running true to form,” I said. We were both just making words.

Looking up, I caught a young captain’s eye. He didn’t turn away when our gazes met; he didn’t change expression; he just watched us with the intent stare of the analyst.

The head waiter came quickly up the four steps from the dining-room with bleak eyes and a painted smile. He was a slight, round-faced man with a short sharp nose and thin, plastered hair. “We are sorry, but all the tables are reserved,” he greeted us blandly in a high, careful voice.

I looked down at him with a broad smile that went all down in my throat and chest. It was all I could do to keep from putting my finger in his face. “Don’t be sorry on my account,” I said, slightly slurring the words with too much throat. “I have one reserved. Jones – Robert Jones.”

The painted smile came off, leaving slackness in his face, and his eyes looked trapped. “Jones, Mr Jones…”

The ‘Mr’ almost strangled him, but he recovered quickly. “Certainly, sir. I’ll have to consult my lists for tonight. We have so many unexpected officers whom we must serve, you know.” This time his smile included me.

But I wouldn’t accept it. Alice squeezed my arm.

He turned, left us standing on the platform at the head of the entrance stairway, walked the length of the dining-room, and disappeared through the doorway into the pantry.

“He must keep his lists in the icebox,” I said, and Alice squeezed my arm again.

I jerked a belligerent look at her, then suddenly felt good all over. She had regained her control and she looked so poised and assured and beautiful, standing there among the white folks, I filled right up to the throat. I noticed a number of the white men sliding furtive glances of admiration at her, and I thought, “You just go right on and keep yours, brothers, and I’ll keep mine – and won’t miss a thing either.” Alice looked up and caught me looking at her and I winked.

“You’re a cute chick,” I said. “How ’bout a date?”

She smiled. “It’s nice to go out with you,” she whispered. “I feel so well protected.”

I didn’t get it so I just grinned. But when several other diners came up, walked past us down into the dining-room, and were seated by the captains, her smile faded. I began getting on my muscle again; I looked down over the sea of curious faces disdainfully. Breath started choking up in me and I thought, Tomorrow I’m going to kill one of you bastards, and it loosened up again. I lit a cigarette to steady my hands, thumbed the match toward the sandbox.

Finally the head waiter returned from the pantry and now he was affable. It was more insulting than hostility. He led us down to the last table by the pantry door and beckoned a crooked-faced, slightly stooped Greek waiter to take our order.

“We came here to get something to eat out of the kitchen, not to eat in it,” I said.

The head waiter lifted his brows. “I don’t understand.” He shrugged indifferently. “This is the only table we have vacant, sir. You were fortunate, sir, to get reservations at all at such a late hour.”

“—at all, period,” I said.

Alice looked extremely embarrassed. The head waiter hovered hopefully. The Greek waiter held the chair for her and the head waiter departed. The orchestra began playing something sticky, sweet. I sat down and looked at the menu, determined to get my money’s worth out of the joint. Most of the courses were listed in French and I had an impulse to sail it across the room. Then I laughed.

“Bring us a couple of martinis while I consult my dictionary,” I said to the waiter, and when he left I said to Alice, “I’m going to have some broiled pheasant and champagne and I know the white folks are going to say, ‘That’s the nearest that nigger can find to chicken and gin,’ but I don’t even give a damn.”

Alice’s eyes frightened me; I thought for a moment that I’d lost her. Then she said in an even voice, “A good sauterne would be better with your pheasant,” and I breathed again.

When the waiter returned with the martinis she became more at ease. The knowledge that she could order a meal with confidence set her up again. I started to bring her down but decided against it; she needed whatever she could get from any source, I thought.

“You order for both of us,” I said.

She and the Greek had a fine time discussing food. He was enjoying it too, it seemed, and she was getting her kicks until a woman at a nearby table giggled. Chances are the woman hadn’t given her a thought; but she went into her shell again. Even the waiter noticed it. She finished ordering and the waiter left.

“The greatest, most brutally powerful novel of the best black novelist of his generation.” Chicago Tribune

I looked across at the party next to us. A young ensign with chiselled features sat across from a very blond girl in a gorgeous print dress. Her hair was drawn in a bun at the nape of her neck, showing a small, shell-like ear. I let my gaze rest on her for a moment, taking in the delicate lines of her chin and throat, the sensitive lines about her mouth and the clean curved sweep of her neck. My gaze moved slightly and I looked squarely into the eyes of the ensign. There was no animosity in his gaze, only a mild surprise and a sharp interest. There were two elderly people at the table, probably the parents of one of them, and the man laughed suddenly at something that was said. After a moment he switched his gaze to Alice; it stayed on her so long the blond girl looked at her too. Her face kept the same expression. Alice didn’t notice either of them; she was drinking her martini with a rigid concentration.

I had a sudden wistful desire to be the young ensign’s friend. I would have liked to send him a note inviting them to join us after dinner and go to some night spot. Then I met the frosty glare of the elderly lady. I looked away.

Alice began one of her one-sided monologues, this time about literature. I knew suddenly that she was fighting; that she’d been fighting before, I let her fight.

“Don’t you like to go out with me?” I asked her suddenly.

She stopped talking and gave me a long solemn look. “I always like to go out with you, Bob,” she said. “You make me feel like a woman. But this is the first time you’ve ever made me feel like an exhibit.”

“But I really thought you liked to go to places like this,” I said.

She said without thinking. “But, Bob, with you everybody here knows just what we are.” I didn’t get it at first.

She hadn’t meant to state it so baldly, so she began covering up. “I’m not trying to justify it, I’m just stating how it is.”

“You mean—“ I burst out laughing and people from several tables turned about to stare with disapproval. Finally I got it out: “You mean when you go in with the white folks the people think you’re white.”

There was pure murder in her eyes. “You don’t have to be uncouth.”

“On top of being black too, eh?” I added, chuckling. “Hell, they probably think we’re movie people anyway, or that you’re white as it is. I’ll tell them I’m an East Indian if you think that’ll help. Next time I’ll wear a turban.”

The nearby diners had quieted to listen. Alice got a strained smile on her face and began talking politics. But I wouldn’t let her get away with it. “What are you trying to do now, educate me?” I said.

Neither of us said another word; we were both relieved when it was over. The waiter brought me a slip of paper clipped to the bill face down on the tray. When I picked up the bill I read the two typed lines:

We served you this time but we do not want your patronage in the future.

I started to get up and make my bid, to do my number for what it was worth. But when I looked at Alice I cooled. I could take it, I was just another nigger, I was going to lynch me a white boy and nothing they could do to me would make a whole lot of difference anyway – but she had position, family, responsibility.

The bill was twenty-seven dollars and seventy-three cents. I figured they’d padded it but I didn’t beef. I simply borrowed the waiter’s pencil and wrote: “At your prices I cannot afford to eat at your joint often enough for you to worry about,” and put the note, three tens, and some change on the tray.

The waiter leaned over and said, “If it will make you feel any better I’m going to quit. And you can read what I think about it in the People’s World.”

I looked at him a moment and said, “If you’re thinking about how I feel, when you should have quit was before you brought the note.”

When I held Alice’s wrap I could feel her body trembling. A tiny vein throbbed in her temple and nerve tension picked at her face. On the way out it was an effort to walk slowly; she pulled at me as if she wanted to run. We had to wait for the car. Passing people looked at us curiously. I thought we should have waited inside, but it didn’t make any difference now. When the car came Alice ran out to it and slipped beneath the wheel. I gave the doorman a five-dollar bill, his assistant a couple of ones.

The doorman fingered the five, hesitated for an instant, then said impassively, “Thank you, sir, and good evening,” in his thick impersonal brogue. The assistant said nothing.

“You can always tell a shipyard worker by the tips he gives,” Alice sneered when I got in beside her and dug off with a jerk.

“A fool to the bitter end,” I said, slumping down in the seat. “I’m sorry you didn’t like it.”

I didn’t like Alice very much then, didn’t even respect her.

“I did like it,” she snapped. “Even with you acting boorish. The food was excellent.”

“Yes, the food was delicious,” I murmured.

She gave me a quick angry look and almost bumped into a car ahead as it stopped for the light.

“But for thirty dollars,” I added, “I could have bought a hunting licence, gone hunting and shot a couple of pheasants, bought a quart of liquor and got drunk and gone to bed with two country whores and had enough money left over to buy gasoline home.”

She said, “You don’t have to insult me any more, Bob. I don’t intend to see you after this anyway.”

I took a deep, long breath, let it out. “It had to end sometime,” I said. “I suppose you knew I wasn’t going back to college.”

After that she didn’t say anything. She kept out Hill to Washington, turned west on Washington to Western. I thought she was going home, but at Western she turned north again to Sunset, jerking the big car from each stop, riding second to forty, forty-five, fifty, before shifting into high. She pushed in the traffic, shouldered in the lines, tipped bumpers, dug up to sixty, sixty-five, seventy in the openings as if something was after her.

At Sunset she turned west, went out past the broadcasting studios, past Vine, turned left by the Garden of Allah into the winding Sunset Strip. At the bridle path she began tipping off her lid: seventy, eighty, back to seventy for a bend, up to ninety again. I thought she was trying to get up nerve to kill us both and I didn’t give a damn if she did.

At Sepulveda Boulevard she turned south to Santa Monica Boulevard, then west again toward the beach. It was early, not eleven o’clock, and there was plenty of traffic on the street. But she didn’t even slow.

“I like to go places in a party,” she said suddenly. “Then to the theatre and a night club afterward.”

“With the white folks,” I remarked.

“You go to hell!” she flared, pushing back up to ninety.

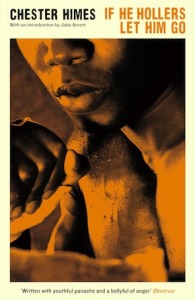

From If He Hollers Let Him Go, published in a new edition by Serpent’s Tail Classics

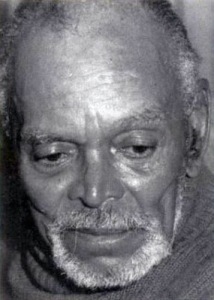

Chester Himes was born in Missouri in 1909 and grew up in Cleveland. As a child he was deeply traumatised when his brother, badly injured in an accident, was refused hospital treatment due to the Jim Crow laws. At nineteen he was sentenced to twenty-five years in prison for committing an armed robbery. During that time he began writing short stories, and after his release published several acclaimed thrillers and novels, including The Crazy Kill, The Real Cool Killers, Cotton Comes to Harlem, Lovely Crusade and an autobiography, The Quality of Hurt. In the 1950s he moved to Paris, and he died in Spain in 1984. If He Hollers Let him Go, his first novel, was originally published in 1945 and is now out in paperback and eBook from Serpent’s Tail Classics. Read more.

Chester Himes was born in Missouri in 1909 and grew up in Cleveland. As a child he was deeply traumatised when his brother, badly injured in an accident, was refused hospital treatment due to the Jim Crow laws. At nineteen he was sentenced to twenty-five years in prison for committing an armed robbery. During that time he began writing short stories, and after his release published several acclaimed thrillers and novels, including The Crazy Kill, The Real Cool Killers, Cotton Comes to Harlem, Lovely Crusade and an autobiography, The Quality of Hurt. In the 1950s he moved to Paris, and he died in Spain in 1984. If He Hollers Let him Go, his first novel, was originally published in 1945 and is now out in paperback and eBook from Serpent’s Tail Classics. Read more.