New directions of our past

by Mika Provata-Carlone

“A book of great erudition, concision and depth.” The New European

It used to be that as a year came to a close and a new one began, an unwritten law beyond remembrance or time also called for acts of similar closure and commencement on our part. A little before, or perhaps slightly after the virtual timekeeping of our humanity went through its annual rites of passage, so did we, at least in theory. Actions, thoughts, intentions and goals were assessed, recalibrated, re-espoused or, if deemed ineffectual or no longer worthy, valiantly abandoned. New directions were taken, new paths were forged, and new deliberations were made with strong conviction, or sometimes faltering determination.

Such an in-tandem motion between our mortality and the world’s atemporality might seem to many to belong to a reality we have long left behind. An irretrievable scheme of things, a frame for our precarious existence that no longer holds its shape. Newness, boldness, unprecedentedness are the new gods and heroes of our days. And yet…

And yet perhaps the roads less travelled, those filled with mystical meaning, a longed-for centre of gravity, the sustaining strength we so much need for a genuine journey into the future, are those old forgotten roads of our past. As we near the crossing line of the second decade of this no longer so very new century and millennium, we might wish to look back in order to go forward; cherish as well as heed all that has come before us in order to make the grandest leap ahead. Those with a keener sense of the figure in the carpet might perhaps discern a certain pattern in our errantry through time, experience and space: we seem to be radical mavericks at the end of what we define as memorable lots of hundreds, and in possession of anxious, roving eyes fixed upon the past as much as on the future once we are a few steps into the new hundred-year stretch that our dissidence and dazzled defiance has just started to create with near-Promethean might. This has been almost unfailingly true in the past, but especially so in the last two centuries we left behind. In both the 1820s and the 1920s a return to ancient groves and grooves of thought and action, to a cultural wisdom and philosophy of life, as well as to the gestures of fashioning a world out of pure materiality, was thought to signal the way out, the way forward, but also the way of continuity that would guarantee the success of historical independence and rebellion.

Today we shun the past; we are particularly suspicious of its cumulative and its particular effects, placing instead our faith, confidence and the thrust of our ambition on the promises of an almost ex nihilo ontology, proffered by our all but autonomous and self-sufficing, fast-galloping technology. Yet what if the way forward was the way back? If in order to make it new, we had to make it old again, with renewed understanding, a fresh perspective, the maturation of the generations that have bequeathed us both traumas and miracles?

Clare follows Bach’s steps as well as the threads and trails of stories he has left behind. He conjures up a panorama of history, humanity, culture, intimacy, with well-tempered verve and measured exuberance”

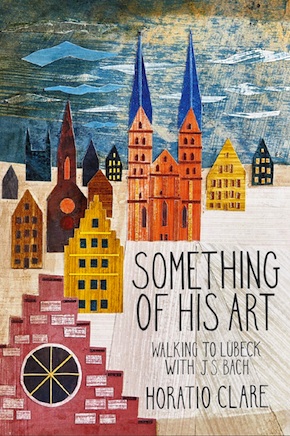

This would seem to be at the heart of Horatio Clare’s raunchy, vibrant and erudite portrait of Johann Sebastian Bach, a man known to most as the epitome of baroque gravitas and poise. A writer’s logbook of a special BBC Radio 3 programme, Something of his Art: Walking to Lübeck with J.S. Bach is almost the equivalent of a pilgrimage for the sake of both art and faith; a catabasis and a resurrection into a new life. Bach made a 400-km journey, “und zwar zu Fusse” – and what’s more on foot – as his son would say, in order to spend time with Dietrich Buxtehude, an organ master nearing the end of his life, the only one who could show him the way forward. It is a journey that was as much a tribute as it was an act of the most radical anarchy, and Bach would be called to answer for his unruliness, contempt of authority, veneration of ancient springs. Clare follows Bach’s steps as well as the threads and trails of stories he has left behind. He conjures up a panorama of history, humanity, culture, intimacy, with well-tempered verve and measured exuberance. He forges out of nothingness the darkness and dampness of 17th-century German roads, the business of an emerging industry, the aspirations to a higher beauty and a more evident affluence in the architectural undertakings and cultural projects of the time. It is a riveting progress backwards, a deeply calming journey forward to a new understanding of Bach’s genius, to a personal revelation, ultimately to a sharing of a gift of existential possibility.

The trip itself is not an original undertaking, neither for Bach nor for Clare. It was standard for new craftsmen and artists to seek an apprenticeship or even ‘wisdom by osmosis’ next to a waning master, and several scholars have sought to experience the energy of the cobbled roads on which Bach trod. Rather famously, Kerala J. Snyder, a musicologist and Buxtehude expert, made a similar trip in 1989 with “a German architect, a Turkish artist and a lawyer”. Yet since this was before the unification of Germany, they could only complete part of the journey. Clare is fortunate to be able not to miss a single pebble, gnarled root, dark ravine or breathtaking view. He religiously visits every awe-inspiring cathedral or church that Bach might have stopped at, and especially each tavern and inn, where he savours both high and low fare, beer and wine.

We learn of the spicy innuendoes underlying many of Bach’s choices or inactions, of the unwitting, semiotic hyper-predication of one of his statues, of his bravado and skills at wielding a rapier and at fending off presumptuous hopefuls; of his stinging tongue when wishing to put someone in what he felt was their rightful place (which suggests a certain discriminatory value system among instrumentalists at the time). Bach could be “laconic, prideful and obtuse by turns… with a mixture of hauteur, insecurity and ambition”, full of “cryptic self-possession”. Yet he was also the quintessential “wandering scholar and itinerant musician”, having studied theology, musical theory, Greek, Latin, French, Italian, the harpsichord, the clavichord, the violin, and of course the organ.

Clare sports a maverick traditionalism, even conservatism, flourishing audacious views, which, although liberal, do not abide (rather thankfully) by the rules of political correctness.”

Bach becomes a pivot, a cultural axis for a Germany that enthrals both with the magnitude of its history and the violence of its turbulences: the darkness of the Thirty Years’ War that came before, the dazzling light of Kant, Goethe or Schiller who would be next to follow. Clare sports a maverick traditionalism, even conservatism, flourishing audacious views, which, although liberal, do not abide (rather thankfully) by the rules of political correctness. This is especially evident in his approach to following both as a disciple and a revisionist critic in the steps of someone so very much larger than life as to be almost, for Clare at least, an incarnation of the sempiternal. How Bach would have travelled, what he would have been carrying in his knapsack, or the options in his tuck box, the absence of travel literature at the time (a thriving genre just a few years later thanks to Goethe, Heine, Rilke, Hölderlin), conjure up a figure as picaresque as he is idyllic, as Tom Bombadil-like as he is an ideal paradigm and luminary.

Plaque commemorating Bach’s visit to St Mary’s Church, Lübeck in 1705 to hear Dietrich Buxtehude play. Wikimedia Commons

Travel emerges not only as a way of relocation, but also of experiencing the changing cultural and social landscape of the time, as an education for one’s sensibility and human awareness, as well as being a way of gathering the necessary inventory of images, points of reference, stimuli for future creation. New technologies, urban structures, civic innovations, the modernisation that followed the war’s devastation and decay, loom as important as the cadences and chords of Buxtehude’s genius. Bach’s process to Lübeck takes place at a moment of monumental transition. What he witnesses will eventually become the new, unchanged face of Germany, and for a modern observer like Clare, the signal point for all recalibration, questioning, or even the angst of horror that our knowledge of the country’s 20th-century future cannot but engender.

Clare is also keen to draw more writerly parallels, weave a tighter intellectual fabric out of the threads of his story, the bifurcating paths of his journey. Quoting Orwell’s words that “only an educated man, who has consolations within himself, can endure confinement”, he transubstantiates a long trek with a mission into a spiritual journey, an encounter with loneliness and even boredom, with existential nothingness and doubt. Bach’s trajectory becomes a symbolic human process, and an individual rite of passage. Landscapes become maps of human experience and the incarnation of sounds that will give birth to rather sublime music, a music that Clare is especially keen to read closely, with deeply engaging skill and engrossing pathos.

This is a particularly rich human portrait and a deeply evocative portrayal of a time, a way of living, thinking, understanding and creating, that is (or, as Clare regrets, can be) no more. The incisive, slanted comparisons with our own moment of change and transition bear a stark, unyielding sense of what one can only call critical nostalgia. As Clare traces Bach’s steps, a host of ghosts, literary, historical, musical, contemporary, ramble along with him, in what becomes a trail of intoxicatingly rich, enchanting revelations and discoveries. Bach’s music, which Clare describes as having existed “through all this time and onwards, beyond foreseeable time… seemingly without… border” emerges quite magnificently, unapologetically, as a topos and a ubiquitous presence, as both time and eternity. Especially as a form of vitally yearned-for salvation: “the nihilism becomes melancholy; the despair becomes reflection.”

Clare’s own trajectory through life emerges as a sensitive compass through which Bach the man, the musician, the pole of a very unique time in history, is conjured up with what one can perhaps call pure enchantment.”

There is a discreet yet dauntless sacred undercurrent in Clare’s text, in his thought, his perception of the world and especially of Bach. A sense of noble longing for a universal order and sense of place we seem to have become blind to. He infuses this sense with quite incredible beauty, with a quiet yet irresistible desirability, a natural nostos that, as he seems to reassure us, could be fulfilled by a simple act of faith, the dynamics of belief beyond the power and drive of all our vital questioning. The ‘something of his art’ that he wishes us to see, that he seeks to retrace and reveal, is perhaps just this, the immensity that can contain both pain and joy, death and life, doubt, despair, even negation, and at the same time the conviction that we can believe in a greater mystery than our own confusion, precisely because we have the power to question beyond questioning itself.

Clare’s slim volume contains an extraordinary narrative that blends story, history and dream. The biographer’s tale rouses a phantasmagoria of facts, chronicles, events, titbits of natural or social history, landmarks of human memory, experience and a much broader landscape. Clare’s own trajectory through life, personal and writerly, emerges as a sensitive compass through which Bach the man, the musician, the pole of a very unique time in history, is conjured up with what one can perhaps call pure enchantment. Ever more arresting is what lies at the heart of this enchantment, a personal odyssey with Bach as the catalyst, guiding light, grid of analysis, interpretation, signification. Music, a particular perspective of the vital role of art, writing, thinking, culture itself as the only redemptive factor of individual and communal life are themes on which Clare composes a powerful eulogy, and in a multitude of ever-developing variations. The loss of a cellist, in his case, leaves behind the priceless gift of Bach’s cello suites.

Music of this kind, a life of this calibre but also of such tangible simplicity and immediacy, attain a state beyond words, beyond trauma and despair, while containing them in their most genuine, unadulterated form. Clare’s Bach is endowed with a language beyond materiality, he becomes even a medium of transcendence and Dasein.

Clare calls his book a gesture of thanks to Bach, and it is above all a homage to what John Eliot Gardiner, whom Clare quotes with particular reverence, called his “sense of certainty, ‘his belief that somewhere there exists a path leading to a harmonious existence, if not in this world, then in the next.’” Even if it is only the shadow of a dream, such a sense of certainty is the perfect way to end and begin a year, a cycle of being, of vital elenchus and of creation.

Horatio Clare’s previous books include the memoirs Running for the Hills (nominated for the Guardian First Book Award 2006 and shortlisted for the Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award), and Truant: Notes from the Slippery Slope, and the essay collections Sicily through Writers’ Eyes and Orison for a Curlew. He has worked as a producer for BBC Radio 3’s Night Waves and The Verb, and Radio 4’s Front Row. Something of his Art: Walking to Lübeck with J.S. Bach is published in hardback by Little Toller Books.

Horatio Clare’s previous books include the memoirs Running for the Hills (nominated for the Guardian First Book Award 2006 and shortlisted for the Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award), and Truant: Notes from the Slippery Slope, and the essay collections Sicily through Writers’ Eyes and Orison for a Curlew. He has worked as a producer for BBC Radio 3’s Night Waves and The Verb, and Radio 4’s Front Row. Something of his Art: Walking to Lübeck with J.S. Bach is published in hardback by Little Toller Books.

Read more

@HoratioClare

Mika Provata-Carlone is an independent scholar, translator, editor and illustrator, and a contributing editor to Bookanista. She has a doctorate from Princeton University and lives and works in London.