Docta puella

by Mika Provata-Carlone

“A fascinating portrait of a woman and her times and a heartbreaking song of the fickleness of love and fame.” The Economist

“This book is about a poet who disappeared, about a woman who pursued her career in a blaze of publicity, while leading a secret life that eventually destroyed her, and who left such a legacy of lies and evasion that her true story can only now be told,” writes Lucasta Miller in the preface of her outstanding, enthralling biography of Letitia Elizabeth Landon, a poet in the wake of high Romanticism, writing and living during ‘the strange pause’ – that peculiar time between the ecstatic anarchy of Byron, Shelley, Keats and their generation and the onset of the decidedly corseted Victorian regime. In this “post-Byronic era”, as Miller calls it, “the ‘poetess’ became culturally supreme.”

Landon (or L.E.L. as she would style herself, in what Miller argues was a clear gesture of “poetic branding”) laid claim as few others did at the time to the kind of radical fame and glory that would make her a favourite and an outcast with equal ferocity. She was admired by the Brontës, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Edgar Allan Poe, Goethe and Heine, as well as the more recalcitrant Thomas Carlyle, was feted in the grandest salons, and pilloried to an extent of almost total erasure in the aftermath of several scandals, and especially as a result of the sharp change in historic and sociocultural tendencies. Landon was ahead of her time as well as existing in a no man’s land as regards female space, voice and being.

Since Germaine Greer’s 1995 study Slip-Shod Sibyls: Recognition, Rejection and the Woman Poet there has been increasing new interest in Landon, her work and her life. Miller’s biography is a masterful culmination of what one might call a collective project to rehabilitate her, decipher her, contextualise and celebrate her. L.E.L. is nonetheless unique in the richness and originality of its scholarly achievement, the intellectual rigour of its argument, the exhilarating momentum of its prose and narrative. Read it at leisure, and it is pure indulgence; read it at a brisk pace, and it is an unashamed thriller, a Conan Doyle mystery, suspected murder and exotic villains included in ample abundance.

L.E.L. is as much about Landon as it is about poetry sub specie aeternitatis, about the emerging role of women in the modern world, but also about simple lives. It is a highly dramatic account of the social politics behind the ultimate persecution and ostracism of the Romantics, as well as a deeply reflected study of the misconceptions that abound about that literary generation and its members, the misnomer that is the Romantic label attached to that particular “movement of the soul”, as one proponent would define it. Like Theodore Ziolkowski, Miller too positions herself against the single tradition viewpoint when dealing with Romanticism, adopting instead a highly polyphonic and multilayered approach. Embedding new historicist and cultural/materialistic feminist analysis, Miller gives us a sweeping yet engrossingly thorough survey of history, society, art and culture, and in a manner that reveals how very organic the sense of a resolutely European connection, identity, discourse and persona was for England at the time – for both Romantics and their critics.

Landon in Miller’s hands develops as an almost prophetic and martyr-like figure all at once; she is also a foil, an ingenious conceit for Miller to embark on a chilling anatomy and survey of the times and their mores.”

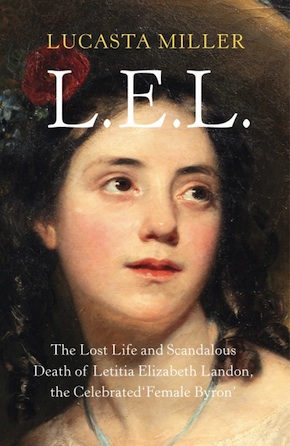

Letitia Elizabeth Landon (Mrs Maclean) by Conrad Cook, after Henry William Pickersgill, 1830s © National Portrait Gallery, London

Landon is shown to be a highly complex figure throughout, even though her actual poetic talent can only be called equivocal. An intriguing example of female self-invention for her time, she combines almost every extreme: brilliance and triteness; a crude ambition and the most radical mind; an enhanced social consciousness and an unyielding pragmatism; dreamy fragility and dauntless resilience. One cannot summarise her, quantify or formulaically define her, and Miller marvels her reader with her skill in capturing each evanescent facet, with a particularly heightened sense of empathy and insight, yet without the slightest hint of intellectual compromise. Landon in Miller’s hands develops as an almost prophetic and martyr-like figure all at once; she is also a foil, an ingenious conceit for Miller to embark on a chilling anatomy and survey of the times and their mores.

L.E.L. is an intense exercise in close reading and critical analysis, a genealogy, a lyrical elegy to a female author, a woman, a poetic voice that strove for the balance between art and fame, talent and popular and material success. Miller’s chosen perspective is that of Landon’s uniqueness as a woman trying to break into the male-dominated enclave of Romantic poetry – the audacity this signified, the sheer force of spirit, but also the less sanitary, tacit agreement to compromise and accept the rules of what emerges as an archetypal patriarchy: “If Byron was commonly dubbed a fallen angle, L.E.L. embraced the proverbial figure of the ‘fallen woman’ as her doppelganger and covert competitor.” More than that, Landon is, Miller tantalisingly argues, an Oscar Wilde avant la lettre, employing high camp and kitsch (both in terms of her writing and in terms of her self-image and image making) in order to resist and subvert, provoke and undermine established structures of perception, and essentially male cultural domination. “Her project of poetic sentimentalisation was a textbook reflection of Schiller’s theory… that art could no longer directly express authentic feeling. Instead, it had to translate banal experience into idealised formulae”, into Idealtypus. It had to, in Lacanian terms, to sublimate in order not to feel. Landon for Miller is such an antisentimentalisch rebel, an anti-heroine in the poetic establishment of the time. She is especially a proponent of Fichte’s Ich/Nicht Ich principle of the split, essentially centrifugal, Romantic psyche. Her sense of ‘self-voyeurism’ and exhibitionism through literature are a “mix of disinhibition and cold calculation”, but also and emphatically an authorial trope, even a cry of despair against constraints and expectations, ambitions and necessities.

This is not a disciple’s Christology, but a defiant, fiercely intelligent apologia for a female life lost – in so many complex, vital ways. Miller is not a neutral observer or chronicler. She takes particular, often ironic delight in unearthing new information, in exposing missing links, redressing errors, and even in indulging in some rather exciting and altogether highly ingenious extrapolations. She resists the modern academic trend for a catchy novelty act, offering instead serious and riveting scholarship, while being unfailingly and enormously engaging. L.E.L. begins with a dead body in the library and maintains its pace of scandal, mystery and intrigue with particular gusto and flair until the story’s all too human pinnacle of tragedy.

We learn about the politics and rituals of publishing, the imperative to obsequiously accost editors, attract benefactors, or the need to extricate patronage and secure the honour of bestowing a dedication to persons of social, if not literary influence. The literary world emerges from Miller’s analysis as a reckless, ruthlessly ambitious universe, fraught with egomania, vice and deviancy – not unlike the banking world depicted in Caryl Churchill’s Serious Money. Publishing is ‘Darwinian’, cut-throat (literally), self-harming and deadly. Landon is in many ways an underdog, an outcast even by the standards of that highly hybrid, intermixed, often incestuous society. She is not a Brontë, a Mary Shelley, or a Dorothy Wordsworth, certainly not a Lady Caroline Lamb or a Juliette Récamier, much as she would have yearned to be. She is in many ways an astonishing phenomenon, a curio, an aberration to the norm, a ‘woman of no substance’ who claimed the space of both notoriety and erasure.

Miller creates scintillating contrasts between her heroine and other female figures of the time – Madame de Staël, Georges Sand, George Eliot, Christina Rossetti, Mrs Gaskell, Shelley and Wollstonecraft, Felicia Hemans, Austen and the Brontës, or Mary Robinson; one hears clearly the echoes of many others, such as Harriet Beecher Stowe or Louisa May Alcott. Or even fictional ones, such as Madame Bovary, who might have made a rather eerie, striking counterpoint. Sociologist, ethnologist, literary historian and critic, Miller is an astute, very intense storyteller. She is keen to show us the vulnerable human individual behind the public mask, the vitriolic, toxic social reality belying the order and decorum, the rust underneath the glittery facade, the darkness behind the dazzling triumphs of the Empire. L.E.L. is almost a manual of the mid- to late 19th century from every possible perspective, dizzyingly and intoxicatingly revolving around this one, singular, forgotten woman. L.E.L. starts with a suspected murder and traces the stages of the death of an era – however illusory or constructed that era may have been.

Rewriting, neo-writing, neo-everything almost, was at the heart of the Romantic project, and much can be revealed if we look at the layers of their palimpsest, not all of them benign, worthy or even admirable.”

One other angle that might perhaps shed further light on Landon and the notion of the female poet, the ‘poetess’ that Miller identifies as the crucial cultural force of the times, is the appropriation of the model of the female improvvisatrice – a model Miller does explore in rich depth, and traces back to Madame de Staël’s novel Corinne, noting that there were numerous Corinnas inhabiting the female Romantic landscape. The real key here, however, is the actual origin of the name Corin[n]a, which provides an incisive perspective into Landon’s persona as the eternal ingenue, the perpetually girly, adolescent female genius – and that is the docta puella of the Romans. It also provides a sociohistorical context for her shadier aspect as a docile, compliant Galatea to William Jerdan’s Pygmalion (or Svengali as Miller prefers to call him).

Corinna was a Greek poet from Tanagra, celebrated in her time as the equal to Pindar, whom she was said to have outperformed in several poetry contests and even put in his place with a rather famous injunction to “sow with the hand, not the whole sack” when it came to tapping the rich resources of the mythological tradition. She would be made famous (colourfully, transgressively and daringly) by Ovid, who uses the name for his puella in the Amores. She is his object of erotic desire, his double-edged pun, since his Corina could also etymologically be derived from kore – she is his young maiden, his little girl. She is especially a dark puella malleable to his every will, and a maverick accomplice to his project of subversively rewriting the stories of men, gods and their myths.

Most Roman poets had their own puella – a mortal muse to add to the nine immortal ones. Catullus had Delia, Propertius’s own famous puella is Cynthia, learned and accomplished, and also, significantly, socially obscure. She is not a matrix, but a girl far below his rank, intended for leisure and for pleasure, to titillate the body and entertain the soul. She is also, quite significantly, his pupil as a budding poetess, his creation ex nihilo, a vessel of his wisdom and mastery – Maria Wykes revealingly has called the puella archetype in Latin grammatology not simply docta, but scripta, in a chilling foreshadowing of future male mentor/female pupil representations across the ages, of Heloises old and new (Little Women acquires a striking new lustre under such light). Through Ovid and Propertius, the docta puella becomes a topos, a female myth (Ellen Moers calls Madame de Staël’s Corinne the “fantasy of the performing heroine” without referring to the classical antecedents). Moreover, the cultural marker of the young elegiac woman, ambiguously positioned between object and agent, bella and scriptor, erotic fancy and poetic flight, was well known to the Romantics. William Blake drew a portrait of Corinna for his Visionary Heads series, and Jonathan Swift penned a highly unambiguous poem to her (dis)honour, A Beautiful Young Nymph Going to Bed. The Romantics were addicted to the classical tradition not only for its tremendous power and beauty but also for the formidable sense of freedom it afforded – the release of the imagination that it promised. Classical allusions provided them with the necessary elusiveness and elision they craved, the escape and thrust forward they desired. Yet at the same time these historically and culturally removed references provided a covert structure for preserving a system of hierarchy and order even as the Romantics claimed to rebel against a more recalcified imperialism – and the puella paradigm is a particularly poignant, troubling one.

In Landon’s case, it helps interpret more critically and historically both the thematology of her poetry and its fundamental weaknesses and failings – she did not have the necessary culture or education to forge that ironic engagement with the classics that was the hallmark of Byron’s generation, the consciously subversive mimesis that was a gesture of both allegiance and revolt. More than anything, her determined yet ambiguous relationship as a ‘poetess’ with her literary ancestry reveals our agency in our constant interaction with the past. The cultural, social, historical choices that we make, the adaptations and rewritings we promote as being more expressive of the human condition, the value of society, the place of the self, the future, perhaps, of civilisation. Rewriting, neo-writing, neo-everything almost, was at the heart of the Romantic project, and much can be revealed if we look at the layers of their palimpsest, not all of them benign, worthy or even admirable. Yet the process of looking closely, of tracing the steps that led to the multiple destructions and reconstructions that have led, inevitably, to our own perception of time and eternity is both vital and thrilling. L.E.L. offers just such a journey and vision.

Dr Lucasta Miller is the author of The Brontë Myth and a critic, biographer and editor whose work has appeared in publications including the Guardian, The Economist and the Independent. She has been a visiting scholar at Wolfson College, Oxford and a visiting fellow at Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford, is a regular speaker at conferences and literary festival, and has broadcast on the BBC and NPR. L.E.L.: The Lost Life and Scandalous Death of Letitia Elizabeth Landon is published in hardback and eBook by Jonathan Cape and Vintage Digital.

Dr Lucasta Miller is the author of The Brontë Myth and a critic, biographer and editor whose work has appeared in publications including the Guardian, The Economist and the Independent. She has been a visiting scholar at Wolfson College, Oxford and a visiting fellow at Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford, is a regular speaker at conferences and literary festival, and has broadcast on the BBC and NPR. L.E.L.: The Lost Life and Scandalous Death of Letitia Elizabeth Landon is published in hardback and eBook by Jonathan Cape and Vintage Digital.

Read more

lucastamiller.com

@JonathanCape

Author portrait © Sim Cannetty-Clarke

Mika Provata-Carlone is an independent scholar, translator, editor and illustrator, and a contributing editor to Bookanista. She has a doctorate from Princeton University and lives and works in London.