The dolphin children

by Moris Farhi

“A future fable aimed at the very heart of our troubled times. This is a vivid, urgent testament.” Lisa Appignanesi

Belkis and I met when we were sixteen.

Numen prides himself as the architect of the country’s ‘robust’ economy, a feat he achieves by laundering billions of dollars, via private banks, to help Iran and North Korea circumvent the international sanctions imposed on them – a service that reputedly also rewards him with tea chests of gold bars.

Numen stipulates that the destitute, the homeless, the unemployed, the LGBT, the disabled, the geriatrics – the asocials in fascistic parlance – must be swept under the proverbial carpet to preserve the country’s lacquer of prosperity. Marooned in Termite Mounds – Social Services’ euphemism for orphanages – Belkis and I fell into the asocial category.

There was one annual holiday, Salute the Saplings Day, decreed by Numen to seduce the new generation destined to extend the era he was tirelessly engineering. Orphans were included. These Youthfests, he declared, would not only soothe the youngsters’ impatience as they journeyed to maturity, but also smith them as tomorrow’s swashbucklers. The jamborees offered elaborate parades and sports meets for elite academies, and fairs for runt schools and orphanages. Showpiece events were televised, and focal points were decked with billboards bearing Numen’s portrait above his proclamation that the blood in his veins is the true blood of patriarchal love.

While ultra-generous with huge tax exemptions to corporations that support him, Numen is a scrooge when it comes to welfare. He considers such charitable diversions as mobile clinics, soup-kitchens, old age homes and orphanages a burden on a country striving to become a superpower. To no one’s surprise, he relegated the orphanages’ fairs to humble venues. Our orphanages – albeit miles apart – were allocated a ramshackle eatery in the grounds of a defunct Carmelite monastery on Key Picayune, the smallest of the circlet of islands lying some six miles off the metropolis. According to a legend, Key Picayune owed its bantam size to a divine mishap: God, while creating the islands with His saliva, ended up with a dry mouth and could only manage a measly spit for the last one.

Key Picayune was blanketed by strawberries. I made for the cliffs and gorged myself. How could I have known that gluttony hosts a thousand scorpions.”

Belkis’s orphanage, situated in an East Strand hamlet from where a dawn ferry transported the mainland’s produce, was the first to arrive at the eatery. My orphanage came second. A third, from an even farther location, would delay breakfast and rosewater-time by another hour. Since orphanages are run like barracks – reveille at dawn followed by endless drudgery – the delay, allowing freedom to wander, was a boon. Key Picayune was blanketed by strawberries. I was impatient to have my fill. I made for the cliffs and gorged myself.

Accustomed to basic fare, how could I have known that gluttony hosts a thousand scorpions?

My stomach contorted. I buckled, writhing.

A voice, in the dulcet tones of a harp, rippled. ‘All right?’

I looked up and saw ultramarine eyes like the Earth seen from space. ‘Too many strawberries.’

She laughed. ‘Stay!’

I watched as a titian dream gathered some lichens and rubbed them on my face. ‘How’s that?’

‘Good.’

She handed me the lichens. ‘Now rub these on your tummy.’

I did.

‘Better?’

The spasms abated. ‘Amazing! Just lichens?’

‘Jasmin, our janitress, swears by them. Earth’s cure-all, she says. I’m Belkis – like the Queen of Sheba …’

Her affability captivated me. ‘Really?’

‘So, named by the man who found me at a bus-stop.’

‘Oh?’

‘A Jewish tinker, I’m told. Named Vitali. Nothing known about him. I imagine the stars know… Anyway, I hope he’s where all good souls are.’

‘Does that make you Jewish?’

‘Your guess. But somewhere between fair and dark, I must be cross-breed.’

‘Do you care?’

‘Not at all. I’m with outsiders. Strangers, others – the maligned, ostracised, persecuted. Makes them so wise.’

Somehow, I found the courage to free the voice I normally keep locked up. ‘Whoever you are – you’re heavenly!’

‘Blatherer!’

I dared hold her hand. ‘I mean it! Honest!’

She didn’t withdraw her hand. ‘What about you? Where’re you from?’

‘Some Balkan war zone. Maybe somewhere in Former Yugoslavia. All these years – they’re still trying to trace the DPs. I imagine I’m from wherever gingerhairs come from.’

‘The ginger hair is the sun shining in you. You got a name?’

‘I’ve been given a list to choose from. I answer to all. To Wardens I’m Carrothead.’

‘Ugh…’

‘Sometimes I choose names for myself…’

‘Like?’

‘Oric. That’s my favourite.’

‘Very unusual.’

‘It’s from a fable. About an ancient tribe that hugged oaks to absorb their strength. One day a warlord attacked the tribe, killed the men and abducted the women. One youth, Oric, survived. He was in love with Semiramis, one of the abducted girls. He summoned the animals sacred to his tribe: bears, reindeer, lions, eagles, dolphins, whales; and searched the planet, shouting Semiramis’s name. Well, Semiramis had escaped from her captors and settled in Arkangelsk. There she became a dendrologist, studying the inner strengths of pines and spruces. She heard Oric. And they were united.’

God is vindictive. Forever angry! The Great Mother never! She’s all love – like all creators. Women commune with Her – breast to breast. That’s how I knew we’d meet.”

‘Grand story. Can I call you Oric?’

I beamed. ‘I’d be delighted!’

She squeezed my hand. ‘I believe in everything that’s life-enhancing.’

I stared at her, confounded. ‘I can’t believe it. All this time Fate kept me in barbed shirts. Suddenly, she produces a miracle. She let us meet. Can She be kind?’

‘We’re destined for each other. She accepts that.’

‘You really mean that?’

‘I always mean what I say.’

‘Then thank you, God!’

‘Leave God out of it. Thank the Great Mother.’

‘Same thing, isn’t it?’

‘God is vindictive. Forever angry! The Great Mother never! She’s all love – like all creators. Women commune with Her – breast to breast. That’s how I knew we’d meet.’

***

But for the arrival of the children from the third orphanage, we’d have stayed there all day.

I muttered gloomily. ‘We need to get back. They’ll start breakfast.’

Belkis snorted. ‘Let’s forget breakfast.’

‘But –’

‘No buts! Let’s escape!’

‘How?’

‘Down to the sea. The sea loves runaways.’

How could I say no?

We cascaded down the cliff.

I surveyed the tiny beach wondering what to do next.

‘Let’s swim,’ said Belkis.

I hesitated. ‘We don’t have bathing suits.’

She laughed and undressed. ‘Nor do fish.’

‘They’ll be looking for us.’

‘They’ll never find us.’

***

We swam and danced like flying fish.

We encountered eddies and whirled with them.

We raced to a distant crag.

There, concealed by algae and thick moss, we discovered our grotto.

We slipped in.

A dreamcatcher’s gem. Azure, large, beautiful, luminous. A pool purling gently. We became two souls in one, and she became my Paradise.

We watched the end of Salute the Saplings Day from twilit shadows.

Our custodians, infuriated by our truancy, called the police, provided them with our descriptions, then gathered their wards and left.

We hid until the police stopped searching for us.

We made the grotto our haven.

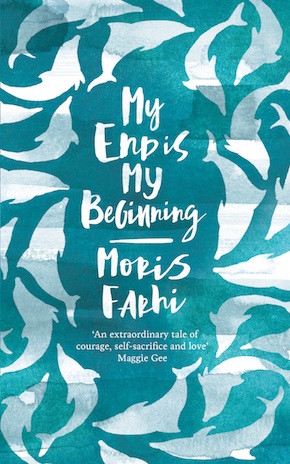

From My End Is My Beginning (Saqi, £11.99)

Moris Farhi (1935–2019) was born in Ankara, Turkey, before moving to the UK. An international human rights advocate, he campaigned for Amnesty International and was both Vice President of PEN International and Chair of the International PEN Writers in Prison Committee. He is the author of the novels Children of the Rainbow, Journey Through the Wilderness, Young Turk and A Designated Man, the poetry collection Songs from Two Continents, and wrote for the theatre and screen. A Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature, in 2001 Farhi was appointed an MBE for services to literature. My End Is My Beginning is published in paperback by Saqi.

Moris Farhi (1935–2019) was born in Ankara, Turkey, before moving to the UK. An international human rights advocate, he campaigned for Amnesty International and was both Vice President of PEN International and Chair of the International PEN Writers in Prison Committee. He is the author of the novels Children of the Rainbow, Journey Through the Wilderness, Young Turk and A Designated Man, the poetry collection Songs from Two Continents, and wrote for the theatre and screen. A Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature, in 2001 Farhi was appointed an MBE for services to literature. My End Is My Beginning is published in paperback by Saqi.

Read more

@saqibooks