Emma Curtis: Face to face

by Karin Salvalaggio

“A terrifying and disorienting thriller that will leave you questioning everyone and everything right to the very last page.” Nuala Ellwood

Writers find inspiration in many places, some more interesting than others. A quick poll on Twitter was met with the following responses: an overheard conversation in a cafe, a photo of a flood on the wall of a local pub, a piece of flash fiction, a news article, and a chance encounter with Martin Scorsese in a warehouse in Queens. The idea might be put into use immediately, shelved until the appropriate time, or never seen again. In a move that must have made him the world’s most unpopular dad, Gabriel García Márquez famously turned the car around, cutting short a family holiday to Acapulco, when the opening line to One Hundred Years of Solitude popped into his head. Most writers can only envy Márquez’ flagrant selfishness. As mere mortals, we’re forced to write our ideas down in notebooks and wait patiently for the family holiday to end.

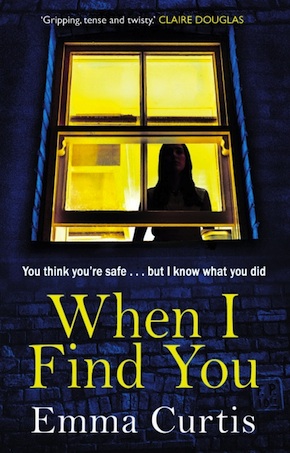

Emma Curtis came across the idea for her recent thriller When I Find You four years ago, and it’s been circling her subconscious ever since. Her protagonist Laura suffers from a hidden disability called face blindness, or prosopagnosia. Often misunderstood, the rare condition provided the perfect vehicle for what is a very interesting piece of crime fiction. I had lunch with Emma at her beautiful home in Petersham and we discussed the inspiration behind her latest novel.

KS: The characters and storyline of When I Find You are well-researched, and you write with an assured hand. How did you come across the idea of centring your novel around a woman suffering from face blindness? Did you interview anyone with the condition?

EC: I first heard about face blindness about four years ago, when I was listening to Stephen Fry talking about his memoir. It stirred something in me, but I didn’t do anything about it until a few years later when I was looking for an idea for my next book. The moment I began researching it, trawling YouTube for ordinary people talking about living with the condition, I was hooked. It gives a protagonist a hidden vulnerability, a vulnerability which, quite frankly, not everyone has heard of and not everyone believes in once they are told. I found people talking about picking up the wrong child from nursery, not recognising close friends, relatives and colleagues, not recognising their own face in the mirror. They spoke of their social and work anxiety, about hiding rather than greet someone they thought they ought to know, about the feelings of panic, the heart-racing and palm-sweating they endured every day. More than the crime possibilities, it was the way of life that drew me to write When I Find You, the constant need to stay alert, frightened of offending, but also not being able to tell friend from foe, that made such a rich subject for a thriller.

Face-blind people develop strategies from babyhood, the same way anyone with a handicap does, so this is their normal. I hope, once readers have taken it on board, it feels as natural to them as it does to Laura.”

There’s never a point when the reader feels lost, even though that is exactly how your central character must feel all the time. It takes skill to portray a character’s confusion without once confusing the reader. We’re there with Laura through all her difficulties, we see the world through her eyes, constantly reminded of her limitations. Were you aware of this fine balance when you were writing?

Yes, absolutely. I didn’t want to keep repeating the message, so after making sure, right from the beginning, that what’s wrong with Laura is explained clearly, the rest had to be shown; played out through her daily routines, her habits, her actions. I was inspired by the story of a cousin who was born with near total deafness but went undiagnosed until he was seven. It’s extraordinary to think that could happen, but it was the fifties, and he was one of five children. In that time he had naturally learned to lip-read. Face-blind people develop strategies from babyhood, the same way anyone with a handicap does, so this is their normal. I hope, once readers have taken it on board, it feels as natural to them as it does to Laura.

The storyline feels very current, in fact sadly so. Two strong, capable women have put themselves in danger because of their relationships with men, be they colleagues or lovers. In the wake of the #MeToo movement any book that deals with sexual assault takes on not only the emotional weight of the act itself but also the politics; in this case, office politics. Were you aware of the growing #MeToo movement when you were writing When I Find You?

To me this book was about Laura’s humiliation as much as the assault itself; that acutely painful knowledge that she has been seen at her most vulnerable, that she has exposed herself to both harm and mockery and been used. I needed Laura to have enjoyed the drunken sexual encounter and consented to it. The point was that she consented thinking her sexual partner was one man, when in fact it was someone else. He knows that he’s humiliated her and is banking on her embarrassment as well as her face blindness to keep her quiet.

I started writing When I Find You about six months before the Harvey Weinstein scandal erupted and the #MeToo movement exploded into our consciousness. Generations of women had brushed off sexual intimidation and power play as ‘part of life’, and suddenly we woke up and realised that what we thought of as something to be endured and not to make a fuss about was not OK. That man who drove me home after babysitting when I was fifteen and touched my face and told me I had beautiful skin was not OK. A minor incident, maybe, but I can still feel his hand on my cheek four decades later, still feel the shock and confusion.

I started writing When I Find You about six months before the Harvey Weinstein scandal erupted and the #MeToo movement exploded into our consciousness. Generations of women had brushed off sexual intimidation and power play as ‘part of life’, and suddenly we woke up and realised that what we thought of as something to be endured and not to make a fuss about was not OK. That man who drove me home after babysitting when I was fifteen and touched my face and told me I had beautiful skin was not OK. A minor incident, maybe, but I can still feel his hand on my cheek four decades later, still feel the shock and confusion.

Laura reacts as any woman would. First comes distress, then shame, then anger, because that’s her conditioning. The question is whether her anger is enough to overcome her shame; whether she’s prepared to point the finger at her attacker. I deliberately didn’t use the word rape until quite far in, and, even then she says, “I think I was raped.” She’s unsure what to call it or how such an accusation would be received. She can’t face trying to explain the unexplainable to the police, so she takes matters into her own hands, with catastrophic consequences.

You excel at writing complex scenes, be they within a busy open-plan office space or at a company Christmas party fuelled by large amounts of alcohol. Were you especially keen to have the reader anchored in each setting because you had an issue with your main character’s unreliability?

It’s great that those party scenes work well, because they are tough. I enjoy the technical challenge that writing a scene with lots of people creates. It’s the trick of filling the space but focusing on the individuals. You don’t want to clutter the scene with other guests’ actions and conversations, but neither do you want to give the impression that your protagonists exist in a void.

I chose a busy advertising agency as my backdrop, because although young advertising execs tend not to wear city suits, they are of a type; so it’s both believable that Laura would function reasonably well in that environment and that she could mistake one man for another, especially when his clothes are hidden by a winter coat.

Despite her protestations, Laura seems to be a natural extrovert but has had to tone down her personality because of her disability. An introvert wouldn’t have engaged their attacker; they would have surrendered, feeling ashamed. In what other ways do you think Laura’s personality has been altered? I imagine she finds it difficult to trust people.

This was very important to me. One of Laura’s defining character traits is that she is naturally outgoing but has been unable to embrace that side of her personality. It wouldn’t be something she thought about as a child, but as a teenager and adult, it would have hit her that her feelings of frustration with herself and with life were due to this bad fit. It’s that inner conflict which both spurs her on and handicaps her.

Though understandable, as it’s behaviour learned over two and half decades, Laura’s silence is at times frustrating. If she’d asked for help and perhaps confided in people she trusted, she’d have been far less vulnerable. Could we talk about Laura’s reactions to her situation? Why has she decided to deal with what has happened to her on her own?

This is the question that everyone asks: Why didn’t she just say, for heaven’s sake? The answer is that some people say nothing at all, some mention it to those closest to them, some broadcast it to all and sundry. Laura says nothing at all – otherwise there wouldn’t be a story.

Someone with face blindness might see a face, but the brain doesn’t file the image, so next time they see that person there is no point of reference, even if it’s just ten minutes later.”

It’s a question worth answering though, and one I did discuss with my sources. One of the reasons we hear so little about prosopagnosia, when two in every fifty people are thought to be face blind to some degree, is that the majority just struggle through. Clearly many people don’t realise they have the condition. If they aren’t aware that they are wired differently from other people, they tend to think they are bad with faces and strive to work harder to remember. It doesn’t help because it isn’t about memory. Prosopagnosia is a learning difficulty. A normal brain sees a face and checks its files for familiarity, has an emotional response as well. Someone with face blindness might see a face, but the brain doesn’t file the image, so next time they see that person there is no point of reference, even if it’s just ten minutes later. The opportunities for causing offence and irritation are legion. It’s an exhausting condition.

You capture the complexity of modern life in London and workplace politics. The heady mix of ethnicities, youth culture, over-crowding, ambition, loneliness, status anxiety, affairs, absent fathers, divorce, drinking and drugs all feel very current. We both know you’re happily married and not in your twenties anymore. What kind of research did you do?

I’m glad to say I’m not in my twenties, but I do remember what it was like. I don’t think times have changed that much. I have always lived in London, apart from a brief stint in Paris as a student. It’s in my blood. Everyone absorbs the place they live in.

My husband works in advertising, so that was incredibly useful, but I had to work hard to get the feel of the dynamics of office life and the particular culture of the industry. I talked to anyone I could. I am ruthless at parties, nosing out people with something to tell me. In fact, I met one of my face-blind sources at a party. The way people connect is so wonderful. You can mention an interest, and odds-on the person you’re telling knows someone who can help. Humans first; YouTube second; then print.

Some readers may not approve of Laura’s behaviour the night she gets drunk and brings a virtual stranger home, but it is her body and her choice. Clearly, it was more than a matter of him wearing a pink shirt and being a colleague. He’s made her feel confident and alive. In the face of this, having someone knowingly take advantage of her disability is devastating. It harks back to the tales of Death and the Maiden. Just as Laura is about to take her first breath of freedom, along comes the spectre of death (as usual, a man) to strike her down. Could you discuss Laura’s behaviour on the night of the Christmas party? Is this meant to be a cautionary tale?

No, absolutely not cautionary! I have been in Laura’s position, blind drunk and getting into a taxi with a man, snogging as it rattled through London… I wouldn’t change my learning curve for anything. Laura didn’t get out much, she was anxious, so she drank. She connected with a man, partly because she was too pissed to worry, but also because she was fed up with being alone. So far, so normal. We do these things when we’re young. Laura didn’t make a mistake in the character of the man she thought she was with. She mistook him for someone else. There’s a big difference.

Emma Curtis was born in Brighton and now lives in London with her husband. After raising two children and working various jobs, her fascination with the darker side of domestic life inspired her to write her acclaimed debut novel, One Little Mistake. When I Find You, her second thriller, is published by Black Swan and Transworld Digital in paperback, eBook and audio download.

Emma Curtis was born in Brighton and now lives in London with her husband. After raising two children and working various jobs, her fascination with the darker side of domestic life inspired her to write her acclaimed debut novel, One Little Mistake. When I Find You, her second thriller, is published by Black Swan and Transworld Digital in paperback, eBook and audio download.

Read more

Facebook: Emma Curtis

@emmacurtisbooks

Author portrait © Liz McAulay

Karin Salvalaggio is the author of the Macy Greeley crime novels Bone Dust White, Burnt River, Walleye Junction and Silent Rain and a contributing editor at Bookanista. Her fiction to date is set in towns that border the Montana wilderness, a uniquely spectacular landscape she fell in love with as a child. Her proudly independent characters inhabit stories about the American dream gone wrong. She is currently working on the final edits of a psychological thriller set closer to home in West London, where she has lived since 1994. The characters may be hemmed in by glass and steel, but the stories they tell are just as compelling.

karinsalvalaggio.com

@KarinSalvala