After the euphoria, the finances

by Rob DoyleRecently I went to the launch night of a literary journal here in Dublin. As is the way with these things, as soon as the readings and speech were done, we all sighed with relief and headed next door to the pub. I was introduced to the author of a novel I had read and admired. She was around my age: early thirties. It’s been a few years since her first and only novel was published to considerable acclaim and success. I asked her what she was up to now.

“Ah, you know, I’m just trying to grow up a bit,” she answered. She then suggested that, in terms of maturity, writers are lagging ten years behind everyone else.

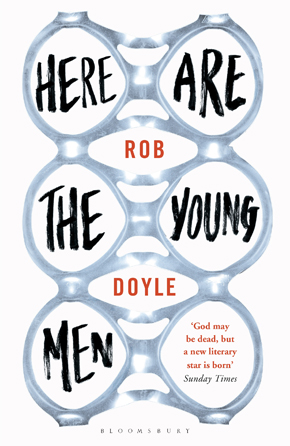

A few months ago, at the age of thirty-one, I saw my own first novel, Here Are the Young Men, finally published. I had written the first chapter shortly before my twenty-seventh birthday. From the outset I believed in the book, and so, rather than admit defeat after I had amassed a fair few rejection letters, I kept at it, even as my friends were clambering free of the rootless, drifting bohemianism that had characterized their twenties, as it had mine. If writers tend to suffer from arrested development, my novel itself, and the struggle to write it, became the agents of my personal form of the syndrome. Everything else in my life fell into neglect. The relationship I was in took much of the strain, then it ended.

I got on with it; the book was published. The reviews were good and people liked it. A major publisher, Bloomsbury, bought it up from the independent, Lilliput, with whom I had signed initially, with the further agreement that both houses would share the publication of my second book. Things had improved.

The words of the writer I’d met at the launch preoccupied me. Now that I’d finally made a name for myself, all those aspects of my life I’d put on hold came into sharper focus. I had no family, no relationship, no property. Christ, I didn’t even have a driver’s licence.

With the advance I’d earned on signing to Bloomsbury, I moved out of the house in a Wexford port town that I’d been ‘renting’ for next-to-nothing from my parents for almost a year, and moved into a house in north Dublin. Then I bought my first car, a ten-year-old Volkswagen Polo. I’m relieved to see it parked on the road outside the sitting room window. Symbol of a belated maturity, it reassures me that, while I did have to arrest my development in order to focus on the consuming business of writing a novel, I didn’t stick it with a life sentence. (Speaking of life sentences, as I look up from my desk and out the window, the sight that greets me is that of a grey prison wall, replete with barred windows, vicious fangs of steel on a high iron gate, and the roofs of grim-looking structures in the middle distance. That’s right, I’ve moved across the road from the jail.)

Writing is a means of withdrawal, a self-cocooning in fantasy and control. But you can’t write without being read, not forever anyhow.”

A car, a writing desk (ten euro from the grimy second-hand lot off Prussia Street), a roof over my head and money enough to keep it there while I put more ink on paper. Okay. My development was arrested but now it’s out on bail. Truth be told, there isn’t a lot I want from life other than the means to do what I’m doing now. That’s part of why I got into writing in the first place: an utter lack of interest in doing anything else, in getting involved with the world. Writing is a means of withdrawal, a self-cocooning in fantasy and control. But you can’t write without being read, not forever anyhow. For a few years, the big thing for me was establishing myself, finding recognition, getting my work published – I needed to foreclose the potential humiliation of devoting myself to something that no one acknowledged me for. Now, with that pressure off, my concerns have shifted somewhat, namely to money. Where will I get it? Will there ever be enough? Or will a life of writing mean it will always be like this: never really settling, just about keeping afloat, enjoying intermittent periods of relative ease before I have to worry again? Maybe, maybe not. I read an interview with Colm Tóibín in the paper the other day, in which he made the unimpeachable point that you’d want to be a lunatic not to be concerned with money. If you don’t have to worry about paying the mortgage, he noted (the mortgage! How remote a possibility that still seems), you’ll have more energy to spend on writing books.

The sensible thing, of course, would be to get a job that provides a regular income, rather than relying solely on the drip feed of payments for articles, stories and reviews, festival appearances and publishing advances. But that would be to act against my belief that literature is diminished by a culture of part-time writers, and my fear that my own work would suffer if I had less time to devote to it. Getting a book in shape takes a huge toll on one’s time, energy and brain activity. Add to this the fact that, other than putting words down, a writer’s chief duty is to read widely and constantly, and the fact of a full-time job (as a taxi-driver, say, or a librarian, or a waiter) comes to seem fatal to the endeavour of writing.

For now, I have enough to pay the rent, do the shopping, buy petrol for my car and keep myself stocked with books. It helps that I don’t have a family to support. If I did, there’s no way I could do what I’m doing now (i.e. nothing). It requires considerable resources to keep the world from sacrificing you to its utility. The role of the writer is the closest you can get to a condition of total uselessness, and that’s why it still appeals to me. Which brings me round to something else I’ve been musing on recently: a large part of a life spent writing books involves not only not writing, but not doing anything at all, so I’ve concluded from reading interviews with other writers, and from personal experience. Having finished one book, you hang around and await impregnation with another. You shuffle between rooms in your slippers, forgetting why you entered the kitchen, then wandering upstairs to the bedroom to forget why you’re there. These stages of the ‘creative process’ are all but indistinguishable from early-onset Alzheimer’s. Sure, you string words together; you write articles for websites like this one; do email interviews; take notes; sketch scenes; write reviews, maybe a short story or two. But really you’re waiting for the next big wave. I’ve come to think of the writer between books as resembling the Zen master with his paintbrush or his bow and arrow: not hurrying into action and thereby spoiling everything, but waiting, motionless and alert, until the movement occurs of its own accord, effortlessly. To the outside world, the waiting writer may merely resemble a fatigued and shambling alcoholic. Still, the Zen-and-the-art-of approach strikes me as preferable to the industrial word-churning some writers still go in for, a seeming transference of the Protestant work ethic into the sphere of literature. My intuition is that we’d be spared a lot of bad books if writers produced new ones only when the pressure built up in them sufficiently that it could no longer be ignored, meanwhile keeping themselves sharp by daily absorption in the study and practice of literature.

If we push that line of thinking to its conclusion, though, we soon come to see that no book ever really needed to be written. Perfectly true. In which case: write away – you might as well. Or quit and get a job as a stuntman or a stripper, or devote yourself to the roulette wheel or fundamentalist religion. It’s all the same in the grand scheme.

Anyway, I’m not going to quit, nor look for more respectable employment. Books are where my loyalties lie, thank you very much. They hold more fascination for me than the rest of the human world, and there’s plenty of graffiti I want to spray on the walls of the universe before I’m taken out. For now, I can afford a pint of milk and some rubber johnnies, and I’m happy to do what I do, and not do what I don’t.

Rob Doyle was born in Dublin and holds a first-class honours degree in Philosophy, and an MPhil in Psychoanalysis from Trinity College Dublin. His fiction, essays and criticism have appeared in The Dublin Review, The Stinging Fly, Gorse, The Moth, The Penny Dreadful and elsewhere. Having spent several years in Asia, South America, the US, Sicily and London, he now lives back in Dublin. Here Are the Young Men, his darkly comic debut about a group of teenagers facing the void of life after school, is published by Bloomsbury in paperback and eBook. Read more.

Rob Doyle was born in Dublin and holds a first-class honours degree in Philosophy, and an MPhil in Psychoanalysis from Trinity College Dublin. His fiction, essays and criticism have appeared in The Dublin Review, The Stinging Fly, Gorse, The Moth, The Penny Dreadful and elsewhere. Having spent several years in Asia, South America, the US, Sicily and London, he now lives back in Dublin. Here Are the Young Men, his darkly comic debut about a group of teenagers facing the void of life after school, is published by Bloomsbury in paperback and eBook. Read more.

Author portrait © Al Higgins

Follow Rob on Twitter: @RobDoyle1